Yep. You read that title correctly. A golden lion’s paw. While this certainly ranks highly on any list of “coolest things ever found,” it is also the inspiration for an amazing collaboration between three institutions that value meaning and substance as much as they do the “Wow” factor. As organizations dedicated to public archaeology and outreach, the Fairfield Foundation, Virtual Curation Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), and Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources (DHR) love to find new and exciting ways to connect people with the artifacts that intrigue and inspire, and this artifact is no exception. But first…a little background.

We are just beginning to learn more about how it was found. Merry Outlaw, curator at Jamestown Rediscovery, shared with us that the sheet-copper lion’s “gambe” or paw was recovered in 1972 from a late 18th-century well on the Bray’s Littletown site near Williamsburg. Archaeologists David Hazzard and Alain Outlaw excavated the well under the supervision of William Kelso, and the artifact was later conserved by either Sarah Gray or Mark Friedhaber. The paw is made of sheet copper, with a gilt surface, and was likely made in England earlier in the 18th century. Merry, who joined the excavation team the next year, recalls that the lion’s paw was already legend amongst the extensive Kingsmill excavations.

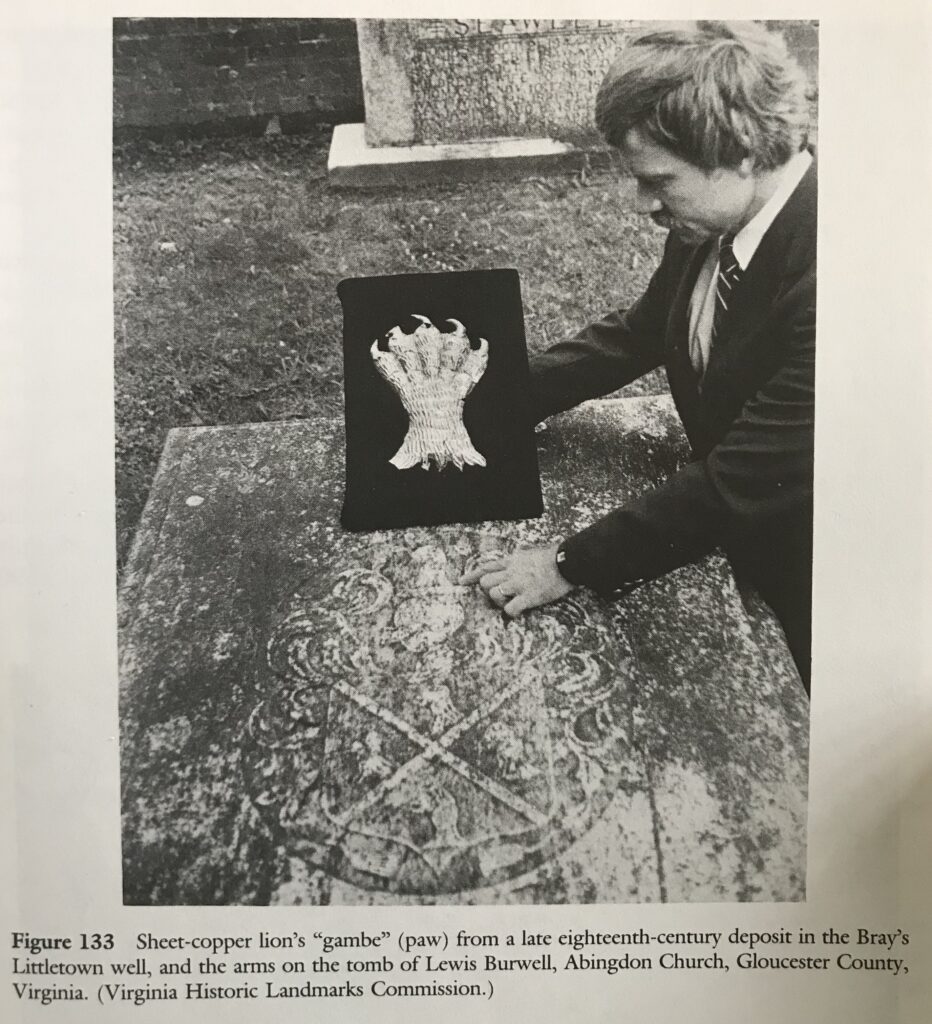

Our own introduction to the artifact was through Kelso’s Book: Kingsmill Plantations 1619-1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia. Every student of historical archaeology has a copy and has marveled at page after page of the amazing discoveries within. The artifact’s meaning grew for us, though, when we began excavations at Fairfield Plantation in 2000. Much of the Kingsmill book focuses on sites of the Burwell family. They not only owned the property at the center of Kelso’s book, but the family tree extended across the York River into Gloucester County to their ancestral home at Fairfield. The lion’s paw is an element of the Burwell coat of arms and Kelso clearly illustrated the connection with a photograph in his book juxtaposing the artifact with the tomb of Lewis Burwell at Abingdon Church. The assumption is that the lion’s paw was displayed somewhere at the Kingsmill manor house, but was later discarded in the neighbor’s well.

The artifacts recovered from the Kingsmill excavation are housed at the state’s primary archaeological curation facility at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), housed at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond. We were always fascinated by the artifact and wanted to see it in person, but the stars never seemed to align for us to visit it…until last month.

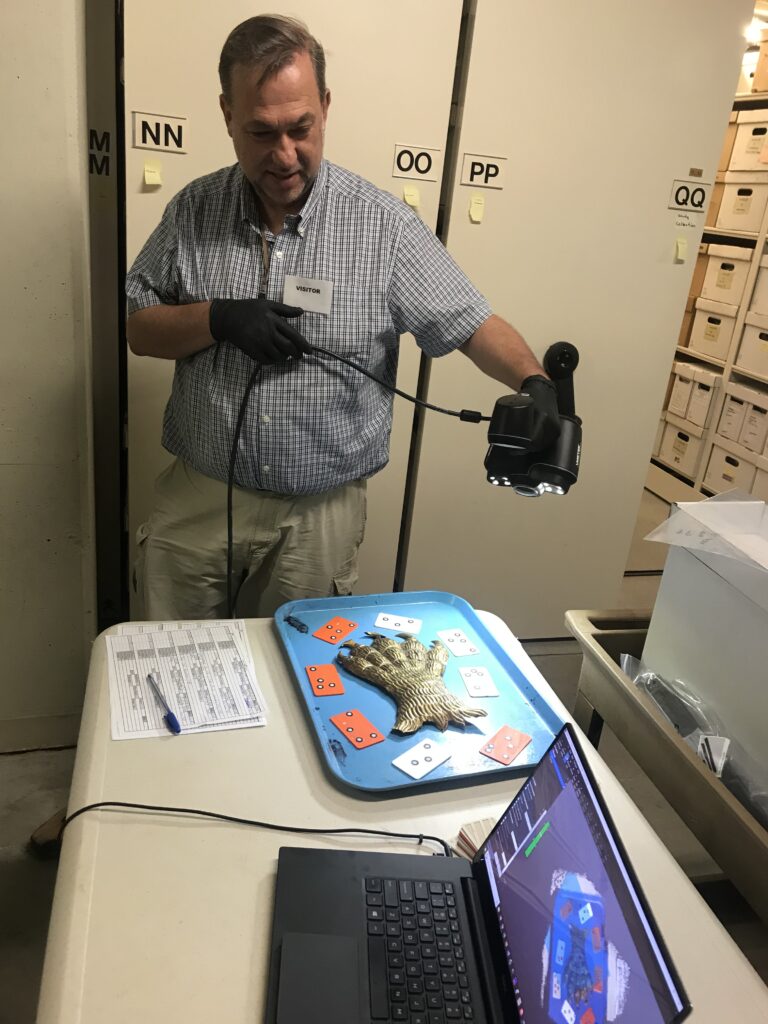

We teamed up with the DHR’s Chief Curator, Laura Galke, and Dr. Bernard Means of the Virtual Curation Laboratory at VCU, to carefully scan the object. The scan will not only create a highly detailed archive of the object’s current condition, but can also form the basis for a printed, 3D version. Dr. Means has pioneered public outreach with 3D printed archaeological objects. Now, one of the coolest artifacts ever found can be held in your hand, printed on your own printer, and incorporated into museum exhibits, while Laura Galke can ensure the object is properly secured and curated in the state’s collections. “It’s one of the neatest artifacts that I’ve ever seen,” Laura told us. “This is a great example of successful curation and collaboration.”

There are still many puzzling questions about this artifact. How was it used or displayed Kingsmill? Why was it discarded in a well rather than retained as a family heirloom? And, a prime question for us working at Fairfield, were there similar heraldic devices used at the Burwell’s ancestral house in Gloucester? We hope further research and excavations will provide some answers.

Thank you for the information on this great find.

I spent a year as the collections supervisor for Ivor Noel Humes Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological lab. I loved the work and wished it had been a course when I was a college student.

I find reading about local efforts to save the history of people through the study of what they used in life.