This research stems from collaboration between The Fairfield Foundation, UNC Chapel Hill graduate student Colleen Betti, and the DAACS Research Consortium based at Monticello. Our DAACS (Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery) colleagues are currently in Seattle for the Society for Historical Archaeology‘s Annual Conference, hosting a session of papers to provide updates on the research projects of various Consortium collaborators and the role of DAACS’s newly-developed open-source software in this research (You can follow @SHA_org or search for #SHA2015 on Twitter to follow the conference proceedings!). The following blog is an excerpt from the Fairfield Foundation’s paper being presented at the conference, focusing on the research discoveries that arose from Colleen Betti’s 2014 senior honor’s thesis at William & Mary.

Trash is an essential window for interpreting the past. Trash on a plantation site, particularly one like Fairfield plantation, which spans the mid-17th through 19th centuries, can open a substantially larger window than on other archaeological sites, since its refuse represents the daily accumulation of detritus from individuals across the economic spectrum – although heavily weighted towards the extremes. From the prehistoric occupations of the Archaic and Middle Woodland periods, to the early settlement of the Burwells and their servants and slaves in the mid-17th century, and through to the plantation’s operation as a tenant farm in the post-Civil War period, there are few eras of human activity unrepresented. But one of the most intriguing eras is the mid-18th through mid-19th centuries, a period that coincides with the most complex archaeological deposit on the plantation: the midden.

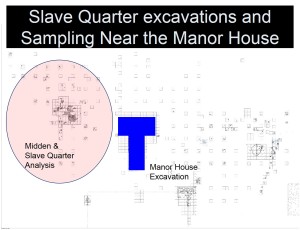

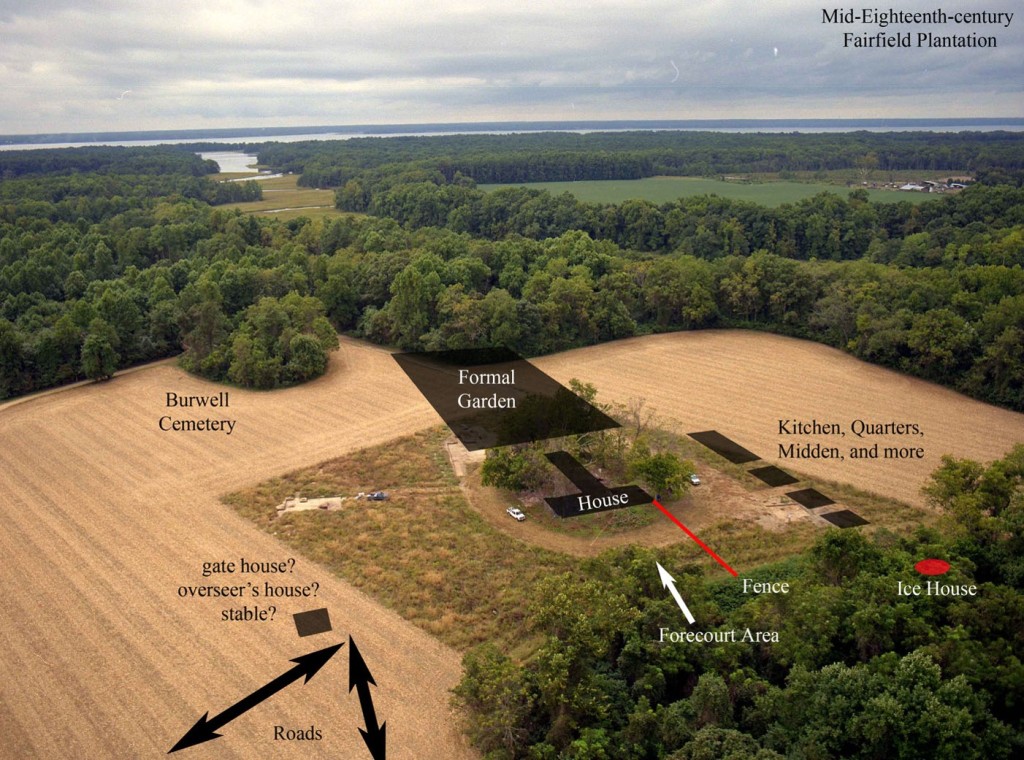

Imagine the intense activity at the heart of a plantation, the intersecting races, classes, and genders, the hustle and bustle of dozens of people of all ages, whether enslaved Africans, visiting politicians, neighborhood craftsmen, or the Burwell family. Residents and visitors intermingled within the planned landscape of one of Virginia’s elite families- a landscape manufactured, maintained and experienced largely by enslaved people. All of the physical goods of everyday life, perishable or permanent, architectural and domestic, personal and impersonal, were eventually discarded or lost within the large trash disposal area west of the manor house, covering a substantial acreage just beyond a line of quarters and other buildings, delineating the work yard from the more formal areas of the plantation’s administrative core. This is one of the most dynamic and interesting places within the vast plantation landscape.

So how do we imagine this? This is, in fact, one of our greatest challenges. How do we better understand this long period, this diverse group of people, and their collective influence on the history of this plantation, this county, and Virginia? We turn to the artifacts to answer our questions. Ultimately, these little bits of the past are the greatest source of testimony to plantation life at Fairfield between 1750 and 1850. We want to know more about the midden itself, but also about who created it, what functions it enveloped, how it evolved over time, how it was defined, and all that it can tell us about the people experiencing this space. For those who have joined us in the field, finding the artifacts is just the tip of the iceberg. The real excitement is asking those questions about what it is, where it came from, what it means- and then actually pursuing the answers to those questions.

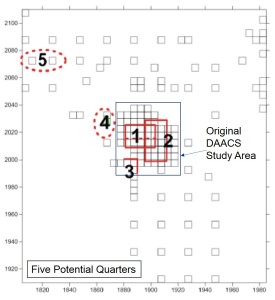

The midden appears to begin forming around the same time as the earliest identified quarter (Quarter 1) at the beginning of the 18th century, soon after the manor house was built. Trash from this and subsequent quarters as well as the main house was disposed of in the same location, to the west of Quarter 1, from this point forward. This includes trash from the kitchen located in the west cellar of the manor house; no trash deposit closer to the manor has been identified.

The blue shading indicates the edges of the midden, indicated by the presence of oyster shell in excavated test units.

There is a distinct edge to the midden matching the presumed west wall of Quarter 1 that can be seen in the above image; it appears as though the midden was being formed while this building was still standing. Trash was kept to the west and perhaps southern side of Quarter 1 and Quarter 2 (which replaced Quarter 1), clearly enhancing the physical boundary between the house yard and the midden yard west of the quarters, and implying distinct differences in the look and activities that took place in both areas.

Betti’s analysis revealed a potential contemporary to Quarter 1 further to the northwest, along the present-day tree line and field edge. This potential quarter (Quarter 5) was identified exclusively through plowzone artifacts and its construction appears to coincide with the beginning of Robert “King” Carter’s management of Fairfield in the 1720s and stood until the Burwells sold the plantation after the Revolution. The addition of this northern building did not move the midden, but rather expanded it.

Evidence from the excavated quarters (Quarter 1 and 2) and the quarter in the northern part of the midden show that the enslaved residents were making deliberate decisions about where they disposed of their trash, and trash from the manor house. Analysis of ceramic fragment size in the space between Quarter 1 and the manor house suggests additional functional differentiation. The eastern part of this yard has few features and little artifactual evidence of activities that may have occurred there. The relative lack of artifacts in the eastern part of this area does not make it less important than the quarter yards or midden, but represents the transition between the domain of the enslaved Africans and the plantation owners.

When the Burwells sold Fairfield to Robert Thruston after the Revolution, activities in the northern part of the west yard decreased to the point that there are very few late 18th- and 19th-century artifacts in this space, but further to the south there are more. No Thruston era structures, other than continued use of the previously built exterior kitchen, have yet been identified in the midden yard, but this distinct shift in artifact patterns suggests an important change in the physical landscape during their ownership.

At Fairfield, the spaces created through trash disposal practices and other activities, namely yard areas and the midden, affected relationships among enslaved Africans and between enslaved Africans and the plantation owners. When the Burwells designated the west yard as an area for quarters, outbuildings and the work yard, and eventually a kitchen, they were imposing their power over the material space and defining social space. They defined the area through the use of fences blocking the west yard off from the formal yard north of the manor. But the construction of quarters and the creation of a midden and other more discrete yard areas points to the more nuanced relationship between the owners and the enslaved. The evidence suggesting that the yards directly east of Quarters 1 and 2 were cleaned more carefully than the area even closer to the manor, indicates that the enslaved Africans were sweeping the yards for their own sake, creating a boundary between ‘their’ yards and the more formal and working spaces of the plantation, rather than just complying with the demands of Burwells. Even more telling may be the midden itself, which was a defining feature of the Black landscape at Fairfield as it was created, maintained, used and traversed by the enslaved Africans, and became a space for much more than just disposal of broken goods.

There is much more to be learned from the midden at Fairfield, both through excavation, but more importantly through the continued analysis of the thousands of artifacts that have already been recovered from the soil. We are constantly asking more questions and reframing our understanding of this complex landscape.