The Fairfield Foundation announced a collaborative partnership with the Gloucester Preservation Foundation last year. As part of our agreement, we will care for Dr. Walter Reed’s Birthplace and the surrounding property while hosting public events and educational experiences there. Though Reed was in Gloucester for only a short time, the house where he was born has many stories to tell about the era in which he grew up and the impact his work had on rural areas like ours, and across the world. The house celebrates its 200th anniversary this year and we plan to have multiple events and blogs marking this occasion and the impacts of Walter Reed.

It’s timely to discuss how to interpret Dr. Walter Reed’s groundbreaking work on the cause of yellow fever. Especially during this pandemic year, we can’t help but reflect on the phenomena of diseases that show up, then and now, as alarming local events (outbreaks), spreading across a region or country (epidemic), and finally crossing national borders (pandemics). One thing yellow fever and coronavirus have in common is that they are both manifestations of the interaction between people and the environment.

Communicable diseases have been recorded since ancient times, commencing when people began to gather in groups that made possible the spread of diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, leprosy, influenza, and smallpox. One particularly fabled pandemic, the 14th-century Black Death, was responsible for the demise of one-third of the world’s population. As people continued to build cities, forge trade routes, and wage wars, pandemics occurred with greater frequency.

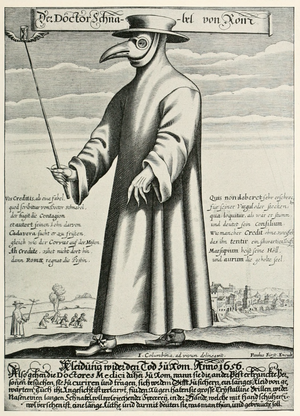

At first, the only thing for city dwellers to do was to flee crowds and quarantine themselves from others. It was believed that the wrath of God was solely to blame. In early modern European society, scholars and early scientists placed the blame on bad air and imbalances in the body’s fluids, so purging and blood-letting were common. Back then, medicine was more like an art aspiring to be a science! By the mid-19th century, microscopes allowed doctors to see small so-called animalcules. It was discovered that their spread sometimes involved vectors or carriers like rats and mosquitoes. Disease began to be understood as the fault of bacteria and viruses.

In colonial and early America, smallpox and yellow fever were the most-feared communicable diseases. A vaccination was developed for smallpox in the late 18th century. But more than a century would pass before it was proved that mosquitoes were responsible for spreading yellow fever, which led to campaigns to remove their breeding grounds: standing water. Another half-century would pass before a reliable vaccination for yellow fever would be developed. From this we see just how much scientific practices have improved, as the cause of the Covid-19 virus and a vaccine to fight it were established in a just few short months.

The yellow fever virus and its mosquito vector, Aedes aegypti, are both of African origin. The disease was first recognized in monkeys and was limited to jungle habitats. Later, it began to infect humans living in towns. Yellow fever was introduced to the Western hemisphere in the 1600s by the slave trade, because water in slave ships harbored mosquitoes. Epidemics of yellow fever killed thousands of people in the Americas, including many Native Americans.

Colonial and early Americans endured recurring epidemics of yellow fever, especially during the summer in seaport cities. Control of the near-annual scourge was limited to the ancient practice of quarantining in homes or in quarters away from towns, as well as the emerging science of sanitation. People avoided one another and an observer of an epidemic in Philadelphia noted, “The old custom of shaking hands fell into such general disuse, that many were affronted at even the offer of a hand.” In a time before germs were linked to disease, physicians saw filth as a reservoir of unknown agents leading to diseases like yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera.

In the years between 1702 and 1800, yellow fever epidemics appeared about 35 times. The “yellow” in the name refers to jaundice, or yellowing of skin and eyes due to excess bilirubin. Symptoms of yellow fever include fever, headache, fatigue, jaundice, muscle pain, nausea, and vomiting. A small proportion of patients who contract the virus develop severe symptoms, usually indicated by black vomit, and approximately half of those die within 7 to 10 days. Ships flew the yellow jack, a yellow flag, to warn of an outbreak of yellow fever on board.

The Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic of 1793 caused many to flee the city, which was then the capital of the United States. Some looked with suspicion on the grubby dockyards and immigrants from the Caribbean. One doctor, Benjamin Rush, blamed the outbreak on spoiled coffee that he found on the docks. Alexander Hamilton was stricken with the disease, but survived. George Washington delayed his usual trip home to Mount Vernon, but finally left, not wanting to risk his family’s health. Doctors were exhausted, homeless orphans became a problem, and the city was running out of burial space. At least one in ten Philadelphians died during the summer and fall, until the epidemic subsided in November.

About the same time as the Philadelphia epidemic, a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States recorded in his journal that he visited a society of Methodists in Gloucester County, Virginia. He met with the group in the home of Joseph Bellamy. By the early 19th century, the Methodist Episcopal Church became the largest religious denomination in the United States. This expansion was largely due to the activity of circuit riders, itinerant preachers who spent two years each attending to a circuit of churches in rural communities.

Lemuel Sutton Reed (1819-1897) was one such man who preached to congregations in North Carolina and Virginia. In 1851, he was assigned to the Gloucester circuit that included Bellamy’s Church. But shortly before the Reed family was expected to arrive, the church parsonage burned down. A small home in the crossroads community of Belroi was found to house Reed’s family, which included five children and his wife, who was expecting another child soon. On September 13, 1851, in this modest structure which still stands today, the Reeds welcomed their sixth child, Walter.

The small house where Walter Reed was born was typical of dwellings in rural Gloucester and throughout Virginia’s Tidewater and Piedmont regions. Dendrochronology, or tree ring dating, indicates the house was likely built in 1821. Originally, the house had one room on the first floor and another on the second. At some point two additional rooms were added to the back of the house, and one of these still survives. The frame house is clad in weatherboard and sits on brick piers. The walls are plastered and the wood trim is plain. When interviewed later in life, Walter Reed’s brother said that the family was cozy and comfortable there. Although small homes like this were common into the mid-20th century, most of them have been lost due to development, or deterioration, making this a rare survival.

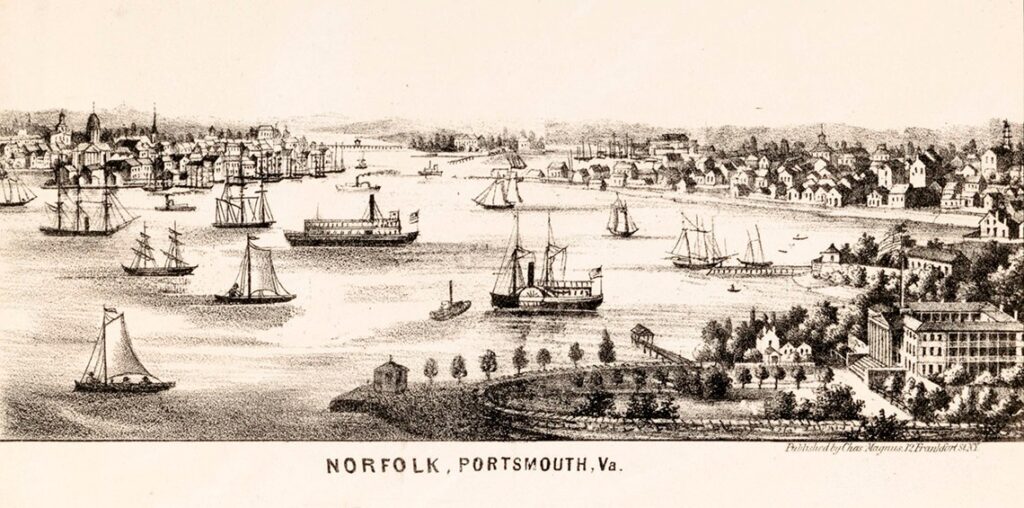

Fifty miles from rural Gloucester was the burgeoning city of Norfolk, Virginia. The city was bustling as a growing hub for oceangoing trade and commerce, and local merchants were optimistic about the future. But in June 1855 the steamer Ben Franklin, which stopped in Hampton Roads en route from the Caribbean to New York, unwittingly brought mosquito larvae in its water barrels. Two men died of yellow fever on the ship. Officials tried to deny the presence of the deadly disease because of the impact it might have on commerce, but by August there was no denying that the disease had spread. Quarantine areas were established in the cities of Norfolk (population 16,000) and Portsmouth (population 10,000). Pest houses were filled with the sick and dying. Newspapers published lists of the dead. Richmond’s citizens were asked to help the widows and orphans who were without food and wandering the otherwise deserted streets. By the end of October when the disease subsided, 10,000 had been stricken and 2,000 had died. The epidemic made an indelible mark on the city, and helped frame the world in which young Walter Reed grew up.

Read more next week about Dr. Reed’s contributions towards understanding and controlling these deadly epidemics.

You can tour the Walter Reed Birthplace (4021 Hickory Fork Road, Gloucester VA) on Saturday, April 17, 2021 during the Garden Week Open House from 9:30 – 3:30.

Very interesting. Look forward to next week’s episode.

Most interesting. Thank you.

Really delighted to learn this history. The restoration seems very good.

David and Thane,

Shouldn’t it be noted somewhere that the Walter Reed house had formerly been located at Purton and was moved to Bel Roi some time before the Hibble’s occupied it. That’s ‘according to an interview that Billy DeHardit had with Clyde Singleton (Clyde’s mother was a Hibble and it was she that gave up the house to the Reed family) in a long ago Glo-Quips article. I can find it if necessary.

We would like a copy of that Glo-Quips article- I don’t think we have it. This is certainly a good thing to mention, but I would love to figure out if there is additional evidence that can corroborate this story.