The house is magnificent. It is everything that you would want in an 18th-century Virginia manor- symmetry, mass, rhythm- and it sits boldly on an elevated landscape surrounded by extensive cropland rimmed with forest and descending towards complex terraced gardens and a wide creek in the distance. It also stands out in the Flemish-bond land of Tidewater, with its rough, brown sandstone walls and thick white stucco contrasting with the two brick chimneys that pierce its hipped roof. It is best known as the home of a “signer”, specifically Francis Lightfoot Lee, an important historic figure who receives less attention than he deserves. Lee, along with his formidable wife, Rebecca Tayloe, and their relatives, owned and operated this plantation during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The place is called Menokin.

A historic photo of the facade of Francis Lightfoot Lee’s home. (Photo courtesy of www.menokin.org)

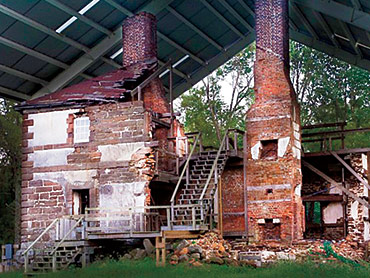

But the house is also incomplete, having begun a slow collapse in the mid-20th century, exposing its failing interior to the elements. Preservationists are endeavoring to stall its deterioration and turn this disadvantage into the one of the most remarkable preservation project of the 21st century.

Incomplete doesn’t simply refer to how it looks today. While there are significant sections missing, including all of its southeast corner and the majority of the northwest corner, gone as well are most of the major outbuildings, and any evidence of enslaved dwellings and agricultural structures. Perhaps the most “absent” part of this landscape is the unseen archaeological record. This part of the story has several chapters yet to share, but the progress to date reveals just how significant the below ground evidence is for rebuilding and interpreting what once was. It has been our pleasure to work with the Menokin Foundation since 2008 to interpret past excavations on the manor house and surrounding landscape, and to continue this effort through several projects that are slowly extracting and excavating the fabric of the collapsed house. The exhausting and time-consuming process of extraction, documentation and excavation is helping to ground the efforts of the Menokin Foundation. Their goal: to transform this home into an educational centerpiece of a forward-thinking and innovative preservation initiative that will influence the field of historic preservation.

The Menokin ruins, extraction and rebuilding in progress.

Extraction is a particularly intriguing word in the context of this project. When John Milner and Associates, and later Jim Gibb and Associates, first undertook their work on the manor house, the focus was primarily on “extracting” woodwork that had fallen into the house’s cellar. They painstakingly documented the location and condition of each rafter, wall stud, floor joist, and other architectural elements so that future architects and engineers could carefully connect these pieces to their place of origin. As many of these elements were deteriorated, and nearly identical in size and shape, their placement in the house cellar could provide key pieces of evidence needed to accurately link them with their original position in the 1760s structure. When we began our work with the Menokin Foundation in 2008, we embraced this detailed documentation strategy, finishing the extraction of wood elements within the central hallway of the basement. Our work over the next few years shifted to stone-focused documentation, clearing the remaining wood fragments and soils associated with the house collapse, but primarily photographing, drawing, and precisely locating the key sandstone elements of the building from the vaulted cellar, hallway, and northern basement rooms. Most recently, we began clearing the deeply filled southeast room and moved to the building’s exterior, particularly at both the southeast and northwest corners. Our work this summer focused on completing the southeast room, in preparation for the substantial rebuild of the basement walls up to the first floor water table, while subsequent work will remove the remaining rubble along the east wall and around the north porch.

Thane stands in the southeast corner room during the most recent round of extraction at Menokin.

Extraction does not focus exclusively on the sizeable or unique stones and wood pieces of the building. It also includes the careful excavation and screening (through 1/4″ mesh) of the tremendous amount of small debris mixed within this above-ground archaeological context. The nails, window glass, metal door and window hardware, and hand-made brick fragments have their own contributions to make to this building’s story, even if they are not re-incorporated into the rehabilitated building’s fabric. They speak to craftsmanship, reveal repairs and modifications to the building’s design, and connect the building and Lee/Tayloe family with the plantation and world around them. They also tell us much about the laborers who built this imposing structure, largely unnamed enslaved and contracted men who left their chisel marks in the stone, the indentations of their trowels in the thick coatings of interior and exterior plaster, pressed the occasional piece of broken pottery or glass into the wet mortar, shaped the thousands of wrought nails used for attaching all the hand-split wood lathing, and revealed their skills as masons in the carefully delineated line of exterior versus interior bricks on the chimneys, and perhaps some of their unfamiliarity with working in stone by the lack of tie-stones in the walls. These mundane materials are at the heart of Menokin, and its preservation will help capture the skill and humanity that goes into building an architectural gem.

An aerial view of the southeast corner room before the rubble extraction occurred this summer.

An aerial view of the southeast corner after the most recent extraction work.

Careful screening of hundreds of buckets of material is also yielding many non-architectural artifacts, which breathe life into this dusty edifice (and literally breathe dust across our worksite and into everything!). These artifacts range from the common (whiteware ceramics, medicinal glass bottles, and animal bone fragments) to the truly exceptional (an 18th-century locket with a lock of hair carefully preserved inside), and together animate the lives of the Lees and Tayloes who lived here, as well as the Boughton, Harwood, Irgens, Belfield , and Omohundro families who followed. A box of batteries, perfume bottles, and dozens of clothing buttons from the early to mid-20th century paint a vivid picture of rural Virginia life on the Northern Neck.

Hidden within the debris of the collapsed house at Menokin were these amazing finds – a little glimpse into the personal lives, and architectural details, of this great house and its inhabitants. Including a copper alloy rosette, a lice comb, springs from a screen door, and various buttons.

A collection of complete bottles found beneath five feet of rubble in the southeast corner.

At the center of this extraction work, in between sifting buckets of archaeological debris and drawing carefully carved water table stones, is the opportunity to merge the lessons of the past with the experience and vision of the future of historic house museums. Our work is complimented and made more significant by the contributions of engineers, architectural historians, and the restoration architects who are designing the structural elements in glass and steel that will allow the rebuilding of this manor. As we uncover and document a collapsed corner, each quoin clearly having fallen away in succession, seemingly stopped in time, we know that the other team members can take this information, assess the conditions of each stone, and design how best to rebuild it, and selecting which stones to carefully set back in their original locations. This effort will not yield a fully restored house, but instead a reinvented Menokin that can better tell the stories of its construction and builders, its residents and owners, and its journey through the centuries.

The section of the northwest corner of the house underwent extraction and archaeology in the summer of 2015. In the collapsed rubble, some of the building corner “quoin” stones were visible and still somewhat in their construction order.

An interior view of the southeast corner room after the most recent round of excavation and stabilization.

In the constant search for accuracy and authenticity, alongside innovation and inspiration, the Menokin Foundation can share with future visitors how the intersection of many disciplines – archaeology, architectural history, engineering, conservation – not only can preserve the past, but also create a new future for it.

Thank you. I enjoyed the article on Menokin and visiting Menokin a year or so back. This reminds me, I need to make another trip back. The architectural material is incredible.

Be well

Thanks. Menokin is a fascinating place and we are excited to be part of this preservation adventure.

David and Thane, this article is beautifully written. Thank you so much for capturing all of the years of work and planning and brainstorming and love for this huge, complicated, groundbreaking project in one perfect narrative. You rock. Pun intended.

Leslie

Thanks Leslie! We love being able to help reimagine Menokin.

So happy all this marvelous work is being done so meticulously to preserve this important place. Thank you Thane and David and your team!

It is a wonderful project and a lot of people have helped out over the years.

Fascinating! Thanks for all that you do.

I was lead on the construction of the concrete footings/foundation for the canopy. The house always had my interest in it, the Lees, the time period, and the surrounding area. From what I remember, more of the house collasped. The historic photo is the first I have seen of the tree that fell on the house starting the collapse

Great work- that canopy has definitely helped preserve the remaining portions of Menokin, and made it easier to do archaeology at the house. You’ll have to come back to Menokin as the house gets stabilized and the canopy eventually comes down.

Tremendous article!

You guys do so much to help all of us grow intellectually and learn about the past. Helps us better understand the world we live in. Can’t begin to thank you enough.

Tom

Mattacock, Virginia