The 17th century was a dynamic time in Virginia history. The arrival of English settlers at Jamestown in 1607 initiated a massive transformation of the landscape, both natural and cultural. The constant influx of European immigrants from the 1620s onwards resulted in large amounts of land opened for settlement. As the colonists pushed the local Virginia Indian tribes out of their traditional territories, they quickly divided up the land by acquiring ‘patents’, or grants of land. Most patents were acquired through the headright system, whereby an individual was due 50 acres of land for each person, including themselves, that they transported from England. For people of some means, this was a great way to quickly acquire large tracts of land that could then be settled with indentured servants who would begin the process of clearing land, planting tobacco, and building the first houses. In this way all of Virginia’s Middle Peninsula began filling with English colonists between the 1650s and 1680s. As access to water was key for these settlers, land with good water frontage was often claimed first, including most of present-day Mathews County (which was formed out of Gloucester County’s Kingston Parish in 1790). What did these early European farmsteads look like?

One of the first projects initiated between the Fairfield Foundation and the Middle Peninsula Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia in 2008 was the exploration of the Bailey site in Mathews County. The Bailey site appears to be one of the area’s earliest colonial settlements, with artifacts likely dating to the 1650s. Our goal is to answer questions about the size and longevity of the site, and obtain more information about how these early settlers managed to survive in this new land. While little is known about the 17th century in Mathews, this century has been studied by scholars for decades, and continuing excavations like those at Jamestown have greatly enhanced our understanding of what happened during this tumultuous century. The Bailey site is representative of the hundreds of farmsteads that sprung up along the waterways of the county, but which have left no visible trace.

Chris Knowlton sorting through pipe stems from the Bailey site.

The Bailey site was discovered by the landowners as they walked the field near their house, picking artifacts off the surface that the plow had turned up. These bits of broken and discarded refuse included dozens of fragments of English tobacco pipe stems, North Devon gravel-tempered ceramic, German stoneware fragments, and dark green wine bottle glass. Each of these artifact types have much to tell us about colonial life, not the least of which is the international nature of the colonial material world. Very few of the finished goods used in daily life were made in Virginia. The tobacco pipes speak to the prevalence of smoking and the prominence of tobacco as the colony’s primary cash crop. The style of the pipes, maker’s mark and decorations, and the diameter of the stem bore can all provide more detailed information about site occupation. The North Devon gravel-tempered ceramic comes from large vessels known as milk pans, which were used in dairies and for other general food preparation tasks. As the name implies, they were made in England and include very distinctive gravel added to the clay body, which makes them easily identifiable. This type of ceramic was widely imported in the 17th century but was largely supplanted by other English earthenwares from the Staffordshire region by century’s end. The German stoneware is from a vessel known as a Bartmann, a jug or bottle with a narrow neck that has been decorated with a bearded man figure. These vessels were shipped from the Rhineland to England in vast quantities until the English began manufacturing cylindrical wine bottles to replace them. The stories behind these artifacts tell us much about the wider colonial world, and give us insight into the daily lives of colonists in Mathews County.

In addition to looking at the surface collected artifacts, we have conducted an archaeological survey of the property to determine the bounds of the settlement. The Bailey site was not large, and after a hiatus during the first half of the 18th century, new residents returned to the site, leaving behind a different array of artifacts that allows us to differentiate between the two occupations. More recent excavations, often including Mathews County school kids, have opened up several test units at the site with the goal of uncovering intact features that will allow us to virtually reconstruct what this early settlement looked like. Post holes dug into the ground for fences and building support posts, ditches, and cellars are all visible as stains in the soil. By mapping in these stains and figuring out which ones fit together, we can interpret the size and location of structures, yards, gardens and other features.

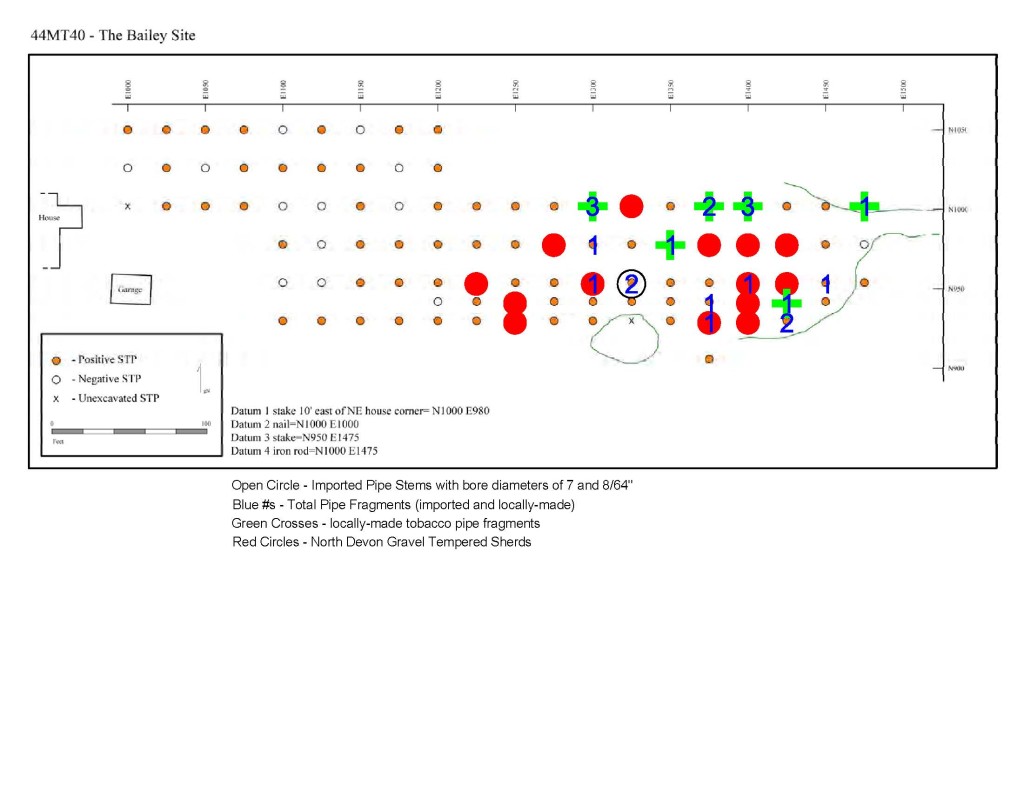

A concentration map, indicating the locations of all shovel test pits excavated on the site, as well as the locations of artifact concentrations, such as pipe stems and ceramic sherds. This concentration map allows us to interpret which areas contain certain artifact types and aids in our decisions about where to excavate future test units.

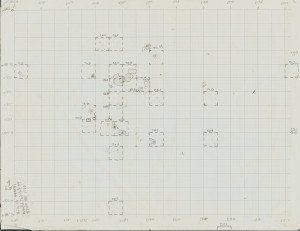

Our field sketch map of the locations of excavated test units and approximations of the features (such as post holes) within those test units. This kind of field map helps us brainstorm about possible interpretations for what we’re finding and allow us to plan strategically for future test unit locations.

But this is a long-term process. Our work is careful and methodical, excavating a couple units at a time, with the eventual goal of understanding the site. Each new dig day, and each batch of artifacts that is carefully cleaned and cataloged, informs our understanding of the site and guides our continued research. In this way we get to involve you in the careful discovery of our shared heritage.

If you are interested in participating in excavations at the Bailey site, or any of the many public archaeology projects that the Fairfield Foundation conducts across the Middle Peninsula and beyond, please send us an email or drop by one of our Tuesday evening lab nights (our web calendar has a current list of upcoming events). If you have interesting artifacts that you have found, please let us know. You too may have found an archaeological site that can contribute to our understanding of the past.