Antioch Church in Gloucester was built by African-Americans who had been slaves at Fairfield and other local farms. While there are many marked burials here, mostly from the 20th century, earlier cemeteries in the area have yet be located.

Antioch Church in Gloucester was built by African-Americans who had been slaves at Fairfield and other local farms. While there are many marked burials here, mostly from the 20th century, earlier cemeteries in the area have yet be located.

On February 8th we had the opportunity to give a brief presentation to the Middle Peninsula African-American Genealogical and Historical Society of Virginia (MPAAGHS) and the Middlesex County Museum and Historical Society. As a follow-up presentation to a lecture by Dr. Michael Blakey on his work with the Remembering, Slavery, Resistance, and Freedom Project, we discussed some of the ways to search for and confirm locations of African-American cemeteries, particularly of enslaved Africans, and what to do once you’ve found them. These challenges apply to anyone searching for the burial site of an ancestor, or looking to preserve sacred spaces in their community. What follows is a short summary of what we recommend, along with some suggested links to help you document these sites and share what you’ve learned with others.

While most of the cemeteries we see today are associated with churches, until the late 19th century, burial commonly took place at small family cemeteries. Sometimes there were stone or wood markers to identify burials, and sometimes memory and tradition alone preserved this knowledge. As land was sold and subdivided, adjacent houses burned or deteriorated, people moved away, and memories went unrecorded, many of these cemeteries have been forgotten. Without the care of a community, headstones have often been moved, re-used, or damaged by vandalism and natural causes. At Fairfield plantation, it took the hard work of Sally Nelson Robins to rescue the Burwell family tombs in 1911 when she raised money through subscriptions and went door-to-door to find tombstones adaptively re-used as door steps. While she assembled a team to move both the stones and the burials to Abingdon Parish church, a similar preservation project at the Page cemetery at Rosewell simply moved and repaired the tombstones, leaving the bodies where they were originally buried. In both instances, attention was paid to the colonial landowning families, with their elaborate imported stone monuments, while the locations of burials for the hundreds of enslaved African-Americans on both properties are still unknown.

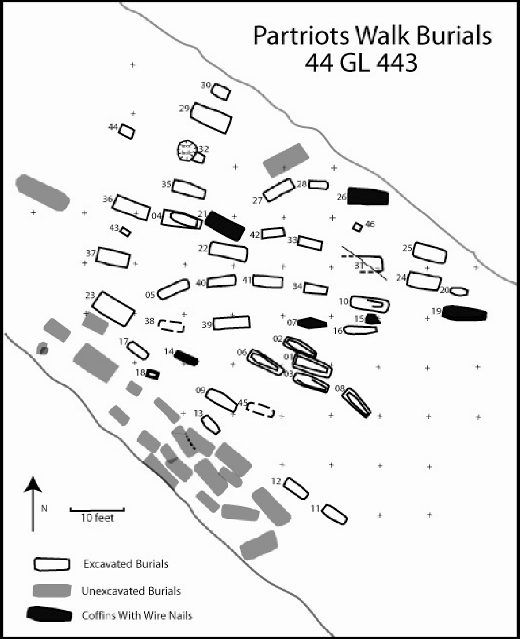

This African-American cemetery, largely forgotten and invisible on the ground surface, was almost destroyed when development came.

This African-American cemetery, largely forgotten and invisible on the ground surface, was almost destroyed when development came.

But suppose you have a suggestion, whether through oral history, a vague map reference or an aerial photograph, of where a cemetery might be. At the edge of a field, or just beyond the plantation’s main cemetery, it is possible to find rows of oblong depressions, one after the other, potentially marking individual burials – not a tombstone or marker in sight. Your first step in confirming the cemetery is NOT to dig. State and Federal law prohibit this. Knowingly excavating or disturbing a burial without a permit is a felony. Rather, your first step should be to record the location and then start scanning through historic documents, whether court records, plats, aerial photographs, maps, church records or family papers that might reference the cemetery. A second step might include mapping the depressions, noting their frequency, their shape and location, potentially finding some markers after gently raking the ground clear of debris. More expensive options for confirming burials include ground penetrating radar (GPR) or soil probes, looking at soil changes that would confirm the cemetery’s presence and extent.

Locating the cemetery is only half the process, though. Once you’ve found it, your next challenge is documenting the location and sharing the information with local historical and genealogical societies, and others who may be interested or have ancestors buried in the cemetery. The more people who know about the cemetery the less likely that it will be inadvertently destroyed by future development. Including it in the property’s legal documents is the best way to protect the cemetery, short of donating a conservation easement on the acreage around it, but there are additional ways to preserve knowledge of these sacred spaces. Registering the cemetery with a local genealogical society, recording it with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), or adding it to the Remembering, Slavery, Resistance, and Freedom Project Database of Cemeteries would bring local recognition, state-level acknowledgement (VDOT, DCR, etc.), and the attention of scholars.

Despite more than fifty burials dating to the 19th century, this cemetery disappeared almost entirely from historic records. Excavation by permitted archaeologists is often the last resort when a cemetery cannot remain where it is.

Despite more than fifty burials dating to the 19th century, this cemetery disappeared almost entirely from historic records. Excavation by permitted archaeologists is often the last resort when a cemetery cannot remain where it is.

The most important and effective way to preserve a cemetery is through maintaining the site and having it known in your community. This is also the most difficult, labor intensive, and time consuming challenge. Few small private cemeteries have funds for maintenance, or a person dedicated to mowing the grass, raking the leaves, and otherwise keeping mother nature at bay. But these “threats” are the most destructive because a forgotten cemetery, reclaimed by forest and field, easily disappears from memory. The key is having a community dedicated to remembering these places, and the people who are buried there.

For more information on cemetery preservation, contact us at fairfield@fairfieldfoundation.org. There are several local organizations actively documenting and preserving cemeteries and a welcoming community of researchers happy to share their resources and ideas. It is our hope we can put you in touch with them and help all of us protect these special places.

Where can I read the results of the studies done on The Patriot’s Walk Cemetery. I am interested because I grew up close by and know the area very well. I checked online and can find no information on it. Thank you for this wonderful web site.

Kindest Regards

Gene

YES! Great article! Marilyn

Really good article! I couldn’t get to the recent presentation on Feb. 8, so I really appreciate the information. Is the report on the Patriot Walk excavations available?

Hello brothers and sisters of Blackness my name is David Anthony powdrill senior I live in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania and I would do anything and everything to be put to rest among my own people my soul will never ever rest if I were placed somewhere among the slave masters descendants

My grandmother showed me the site where she claimed as she said slaves and witches were buried. The site is located just to the right of the logtown cemetery near pearlington ,ms . I believe there are more also located at the older cemetery that is a short distance from there.

I know where there r some graves of slaves on some tn land ,who do I contact before these people try to destroy them or have them covered up

Hi Crystal, it would be best to contact the State Historic Preservation Office to let them know about the graves, or a local historical society if there is one in your area. Slave cemeteries are often not marked and rarely show up in records, so it is important to preserve them when we can.