By Sara Lewis, Fairfield Foundation Development Officer

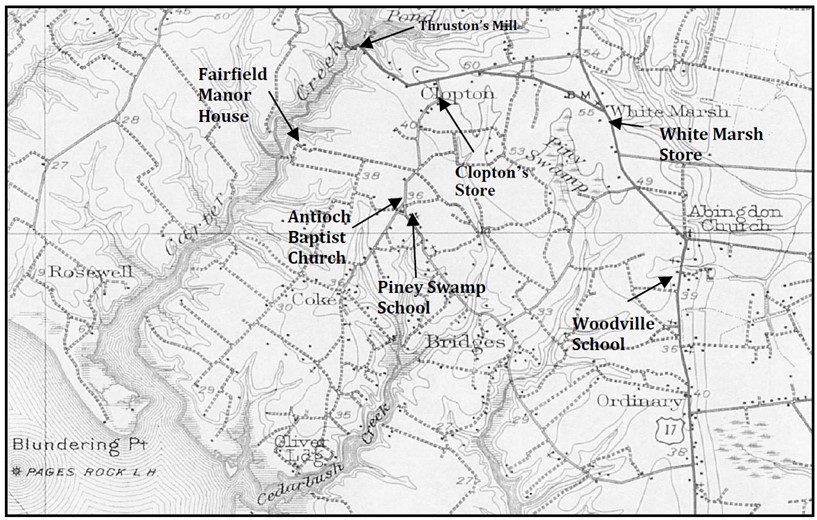

The Fairfield Foundation, a 501(c)3 organization in Gloucester, Virginia, has used its flagship Fairfield/Carter’s Creek archaeological site in White Marsh as one of its locations for historic preservation and educational outreach since 2000. The organization is planning to open the site to the public as a place for exploration and discovery of archaeology and local history.

Until recently, the history of plantations like Fairfield has been the story of European American planters who developed them. Today, people are more interested in knowing the full story, which includes truths about the indigenous people who were displaced and the people of African descent whose forced labor built them. But the written and documented history of these people is not easy to find, and many stories have been excluded or erased. The Fairfield Foundation continually seeks to bring together information gathered from documents, archaeological findings, maps, oral histories, and more. Our mission is to involve volunteers in this inspiring hands-on experience of historical discovery in ways that change their appreciation for the past and actions in the present.

Background

In 1648, Lewis Burwell acquired one of the first land patents north of the York River, in the heart of land formerly inhabited by native Algonquin people. By this time, however, these indigenous people had moved their villages west, while still interacting with the small group of new people from a foreign land. But European settlers were quickly expanding their occupation of Virginia and most saw the native people as savages. They actively sought to remove them, especially as tobacco cultivation was established as the colony’s money-making venture.

To satisfy his need for laborers to establish tobacco, the first generation Burwell (mid-1600s) brought over European servants to work for a period of indenture. Upon completion of an indenture, servants earned a plot of land of their own. A few indentured servants were descended from Africans, making the work groups and some offspring interracial, yet Blacks were a small minority of colonial Virginia’s population.

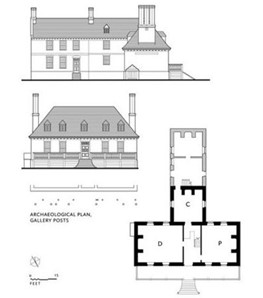

By 1694, when the second generation Burwell oversaw the building of the manor on Carter’s Creek called Fairfield, one of the largest home in Virginia at the time, this had changed. Elite planters were investing in the market for enslaved laborers, who represented 20 percent of Virginia’s population by 1720. Planters like the Burwells acquired more land and slaves to grow a crop that required intensive labor.

The first and second generation Burwells acquired slaves from various sources, including one from a ship sent by the Royal African Company and several Virginia-born slaves acquired from neighbors, including Nan, Yambo, Dick, and Betty. Larger numbers were inherited or acquired by marriage, including Mulatto Kate, Jack Parratt, Tom, and Will Colly. Inherited slaves may have included Yaddo, Cuffey, Denbo, Bungey, Cumbo, Harry, Sue, Jacob, Frank, and Corajo, as well as two Virginia Indians, given the English names Will and Dick. Many of these people or their parents came from Africa in the preceding decade or two.

For prosperous and eager planters like the third generation Nathaniel Burwell, who died in 1721, hereditary slave labor was the established answer to his labor requirements. Slavery had become an established institution and slave labor the foundation of wealth.

Africans and African Americans did more than work in the field. Black artisans included coopers, carpenters, and others who adapted their West African skills. Domestic workers at Fairfield became expert in the preparation and serving of European cuisine.

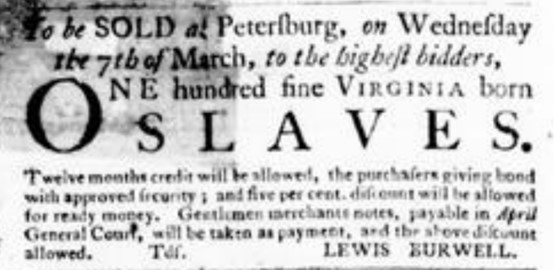

Burwell bought people directly from Royal African Company ships that landed in Chesapeake Bay ports like Yorktown. The people represented a variety of West African ethnicities and languages. It is unlikely that we will ever know enough to trace the individual family trees of many enslaved people who lived, toiled, and died at Fairfield. But research and archaeology continue to recover information about them as a group.

By the time the fourth generation Burwell was an established gentry planter he controlled a 7,000 acre plantation and Virginia’s workforce was almost entirely African American. By his 1736 marriage to Mary Willis, more slaves were inherited. Domestics at Fairfield catered to the needs of the family and a steady stream of guests, especially when Lewis Burwell was appointed as the temporary Governor of Virginia in the 1750s and the Council met at his home in Gloucester.

The fifth generation Burwell, who married Judith Page from neighboring Rosewell plantation, enjoyed the life of a gentry planter, made possible by the corps of enslaved people. But in 1770 he sold 100 of them in Petersburg. He continued to sell off unknown numbers of slaves, probably to pay off his debts related to horse racing and circumstances surrounding the American Revolution. He died in 1779.

In 1784, records show that his son, of the sixth generation of Burwells, still enslaved 163 people at Fairfield and another nearby plantation. These people are not mentioned in his 1785 and 1786 advertisements for the manor house and surrounding land, then reduced to 1,300 acres. When the plantation in its entirety could not be sold, the property was subdivided.

In 1787, the manor and 804 acres were sold to Robert Thruston and Burwell moved to Richmond. During the Thruston ownership, between 15 and 30 people were enslaved on the farm and in the household. In 1850 his son sold the old manor house and 500 acres. Carter’s Creek farm, as it was commonly known by then, passed through the hands of the Leavitts, Cookes, and Wares from the 1840s until the house burned in 1897.

After the Civil War, the farm was leased to black and white tenants. Only six photographs of the house have been found from this period. One includes the African American woman who lived there just before the fire. Will we ever know her name?

Using archaeological research, the Fairfield Foundation is filling in the gaps and asking new questions. During archaeological excavations in and near the manor and on the surrounding property are found the physical remains of everyday life, including the material world of indigenous people, the formerly enslaved, and free people of the 19th and 20th centuries. They left behind such things as African shells, buttons, dishes, shoes, cutlery, tools, food waste, medicine bottles, and toys.

Telling the Story of the Emergence of an African American Community

After the Civil War, facing new social and economic realities, the owners sold, leased, and gifted parcels of land to former slaves to keep some of the laborers nearby, therefore allowing the farm to survive. Randall and Nancy Carter purchased land near the corner of Cedarbush and Hickory Fork Roads about 1880. Others who owned neighboring land included James Cary, Achilles and Maria Johnson, and Anthony Thornton.

The late 19th-century dissolution of white-owned farms on former plantation land aided in the development of an independent and thriving African American community. They joined together as families, civic groups, and churches. They pooled resources to buy land and farmed together to guard against malicious creditors and poor harvest years. In addition to farming, others worked as watermen, artisans, domestics, and mill operators.

By themselves, a list of occupations or a handful of land deeds do not adequately communicate the look and feel of the community, nor the hopes and aspirations of its residents. How did these people build and furnish their homes? What did owning land, a house, or a horse mean to families of this “First Generation of Freedom” in Gloucester? How did they interact with neighboring white landowners, store owners, and residents? Many yearned for a life of better opportunities. They pooled their money to build schools. As a group, they laid the foundation for the next generation, but few personal records from this era have been found. Were their stories passed down to descendants?

Future discoveries that will add their voices to a more complete interpretation rely heavily on an inclusive approach to research and public outreach. It is essential that any approach to understanding the lives of new freedmen and their children and grandchildren, and the choices of late 19th- and early 20th-century citizens involve the descendant community. Not only does the community possess vital elements of the past, such as family papers, photographs, and genealogy, but they are the keepers of oral history and remembered tradition that provide a critical avenue to understanding the past.

The Fairfield Foundation wishes to share knowledge with the community and open a dialogue about our shared cultural heritage. Our goal is to better understand the evolution of this plantation landscape through archaeology-based research from the time colonial settlers first claimed its forested lands, through its turbulent years of growth, war, and decline, to its dissolution in the 19th century. Our goal is to interpret to our visitors that this land gave rise to a vibrant African American community.

But homes and other neighboring buildings of this period are quickly disappearing due to development and displacement. Elders are passing. Discussion with the descendant community is essential for guiding documentation and preservation efforts as research continues into the more recent past. This is a vital part of Gloucester’s history that the Fairfield Foundation wishes to preserve and share.

References

Walsh, Lorena Seebach

1997 From Calabar to Carters Grove: the history of a Virginia slave community. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Brown, David, and Thane Harpole

2020 Fairfield Plantation and the Emergence of an African American Community. Fairfield Foundation, Gloucester, Virginia. https://fairfieldfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fairfield-VFH-Booklet-updated-2020-pamphlet-size2.pdf

What a great article to read on the eve of Juneteenth.

Thanks!

Best, J. Bland

Thank you!

Sara

Actually it is Juneteenth! Started my work day too early today.

An exciting project! Keep up the great work!

Thanks, Bert!

Sara

Lots of great information. So glad you’re helping to preserve this special history!