Blog post written by Elizabeth Donison, staff archaeologist, Fairfield Foundation.

Most of us can agree that 2020 was a year of reckoning with our notion of death, and the Fairfield Foundation’s various projects seemed to align with this challenging and often depressing year. Some of you might remember our participation with the mid-19th-century graves under The Basilica of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Norfolk in May and June of last year. Our more recent project in Urbanna (Middlesex County) was initially a salvage excavation, exhuming human remains accidentally discovered during construction on private property. To make sure no other human remains would be disturbed, we excavated in an area of future impact, finding evidence of a second burial before the backhoe did. And while there was an attempt to move the body in the early to mid-20th century, the act was not complete, leaving much of the deceased’s bones and coffin behind. As we continued to excavate, we found a plethora of coffin hardware and eventually the coffin outline.

Right: Base of the coffin and the early 20th-century cut made to exhume the body.

The coffin hardware pieces were among some of the most beautiful artifacts I’ve uncovered. Their detail and stylistic rendering lead me to believe they must belong to the late 19th-century (also known as the Victorian era).

The word “beautiful” is apt, because in the second half of the 19th century a Romantic movement occurred, a “Beautification of Death”, where the concept of death became romanticized and was seen by the middle class as an escape from an imperfect, unstable, and increasingly capitalistic world.1 The Civil War had just ended in the United States, leaving over 600,000 dead, and the “Second” Industrial Revolution was driving many families apart.2 This industrial revolution in the mid- and late 19th century saw increased urbanization due to centralized mills, plants, and factories that drew in many rural workers away from their homes. Likewise, this period of the industrial revolution further developed a middle class that sought to establish itself through social cues.1 As a result, there was a general shift towards more public displays of mourning. The supply and demand for mass-produced coffin hardware increased substantially alongside the need to demonstrate status through rituals associated with the dead.3

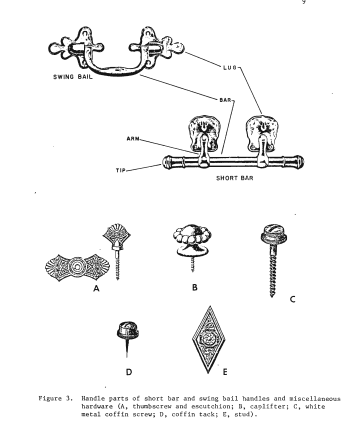

The coffin hardware we found included structural pieces (related to the physical construction and use of the coffin), such as coffin handles and nails, that were not disturbed when the body was removed. In contrast, the coffin lid and some of its associated artifacts were missing. The largest structural pieces were the numerous handles on all sides of the coffin. After cleaning these pieces, we realized they are in a ”swing” form, manufactured in a way that allowed pallbearers to pivot handles upward.1

The handle pieces are composed of a combination of extended bar handles and short bar handles with wood inside the iron grips, as well as lugs, arms, and tips made from white metal (a type of metal alloy that creates a silvery surface).5 The tips appear to resemble crowns while the lugs resemble shields or scrolls.

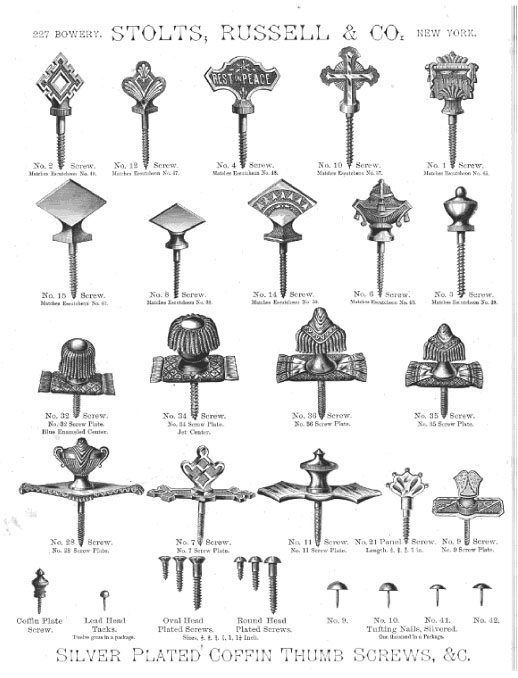

Some of the most intriguing artifacts were the thumbscrews. These artifacts were found in the dirt used to fill in the coffin and disturbed grave after removal of the body. These attached the coffin lids to the coffin body. They underwent three stylistic changes in the 19th century. The screws recovered from this site are third generation thumbscrews (first patented in 1874), with broad flat heads made from white metal.1 These contrasted with earlier versions that either resembled coffin screws or cylindrical urns. The thumbscrews were the first indicators of an ornate coffin and a potentially well-off occupant.

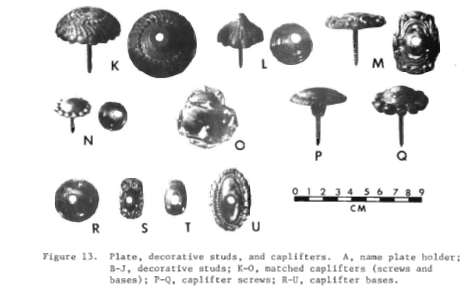

We also found coffin tacks with black fabric, a caplifter (used to lift a coffin lid for viewing) without its screw, corrugated iron fasteners, coffin screws, and iron objects we believe to be closures.

Photo 2. Corrugated fasteners were used to secure two pieces of wood together, and first patented in 1884.5

Photos 3 & 4. Caplifter – These gained popularity in the 1870s and went out of style in the 1920s.1 It mostly resembles the caplifter screws (P-Q) in Photo 4.

The coffin appears to have incorporated many stylistic hardware choices with various dates of manufacture, making it difficult to date to a specific period. We don’t know whether these choices were affected by the popularity of a particular style, the expense of the coffin, personal style preferences, availability, or the limited selection in a small late 19th-century port town. Based on various patent dates and historical trends, however, this coffin likely dates to the 1880s-1890s. We currently know of two people whose bodies were removed from this property and reinterred at Christ Church cemetery (Middlesex County): Alfred Palmer, who died sometime between 1880-1900, and his wife Sophionia (d. 1906). Although Alfred’s death date range matches the coffin’s description, it is also possible that Sophionia and her family selected a coffin with hardware in an earlier style. However, we know there are multiple graves on this property and can not confirm the connection yet.

As with most archaeological sites we encounter, this feature prompts a multitude of questions: Where did the coffin hardware come from – a local source or a catalog? Where was the body reinterred? What was the occupant’s gender? How did they die? Why was their body removed? What was the occupant’s ethnicity? Does their coffin hardware reflect the stylistic trends from the time they were buried?

We might not be able to answer these questions right now (or ever!), but we can infer that the deceased and their family considered burying the dead an elaborate affair that justified a more “beautiful” coffin. Just like today, death felt like an increasingly pervasive entity in the late 19th century. It was so pervasive that it sparked a cultural movement seeking to establish social solidarity to grapple with how to cope with death and its associated emotions; the rituals of burial changed to help cope with the loss of loved ones. Communities built a sense of social solidarity through these rituals, that romanticized death and the afterlife, which further affected all social and economic classes through the material display of ritual knowledge and social status. These sentiments are present in the artifacts we uncovered, and can contribute meaning to how we study Urbanna’s history.

Sources:

1Springate, Megan

2015 Coffin Hardware in Nineteenth-century America. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

2Mokyr, Joel

1998 The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870-1914. Northwestern University https://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jmokyr/castronovo.pdf. Accessed Feburary 2, 2021.

3Bell, Edwards

1990 The Historical Archaeology of Mortuary Behavior: Coffin Hardware from Uxbridge, Massachusetts. Historical Archaeology 24(3): 54-78.

4Hacker-Norton, Debi, and Michael Trinkley

1984 Remember Man Thou Art Dust: Coffin Hardware of the Twentieth Century. Chicora Foundation Research Series, No. 2, Chicora Foundation Inc., Colombia.

5Hill, Mary C., and Jeremy W. Pye

2012 New Home Cemetery (41FB334): Archaeological Search Exhumation, and Reinterment of Multiple Historic Graves along FM 1464, Sugar Land, Fort Bend County, Texas. Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State, Vol. 2012, Article 1.1Bell, Edward L.

Amazing work. So interesting article.

Awesome

Fantastic historical description

Thank yiu

iNTERESTING WORK – found in unusual places

Elizabeth, this is perhaps the most complete, well written, enjoyable write up that I have read in a long time… thank you so much for sharing your skills with us, not only in the field but also at the keyboard…

Very interesting article that relates to most of our country. I am in East Tennessee and found this page by accident while searching for clues in my Burwell descent through the Page family of Rosewell. I am also the head of East TN Cemetery Research and would love to be able to share this with my facebook readers. Can it be done?

Hi Robert,

We would happy if you shared this blog with your facebook readers. You should be able to just cut and paste the link into a facebook post. We have worked at both the Burwell plantation known as Fairfield, as well as Rosewell, for more than 20 years, so let us know if you’re interested in learning more.