King William County, Virginia boasts our nation’s longest continually used courthouse. The 1725 structure is set back from Route 30 amid a cluster of brick buildings inside a pair of nested walls. These include a late 19th-century jail to the east (now offices and restrooms), a mid-19th-century clerk’s office to the southwest (now the King William County Courthouse Museum), and a Confederate monument erected in 1922. For the past several years, the Fairfield Foundation has worked with the King William County Historical Society on archaeological survey and excavations at the complex, seeking to uncover details about the standing structures such as when they were built, modified, and used. Archaeologists have also found evidence for several buildings and features long vanished from the grounds. Recent work focused on locating the historic tavern where locals, members of court, and trial participants gathered after

the proceedings.

The search for the tavern and other lost structures began with Alonzo Dill’s remarkable ‘blue book’ published by the society in 1986. It provided tentative locations for missing buildings like the store, hotel, stable, and taverns. A 1777 Virginia Gazette article mentions John Quarles’ 72-by-20-foot “publick house” at King William courthouse with a full-length portico or porch. The “4 rooms below and 4 above, with 4 closets on a floor” were under the management of various innkeepers who leased the business from Quarles. The documentary record is silent for most of the 1800s, but oral history indicates the structure burned around the turn of the 20th century. Archaeologists seek to pinpoint its footprint and dimensions, the locations of dependencies and other landscape features, and whether “four [rooms] above” meant a dormer-lit garret like the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg or a full second story like the Botetourt Hotel in Gloucester (Va. Gaz., D&H, 26 Dec. 1777).

The Courthouse complex is situated behind a three-foot high brick wall, erected about 1840. It sets the official space apart from the commercial landscape around it, historically including Puller’s Tavern and a livery stable to the northwest and southwest across Horse Landing Road (Rt. 619), a general store to the south, Quarles Tavern to the southeast and Hill’s Hotel across the Old Road (Rt. 1301) and southeast.

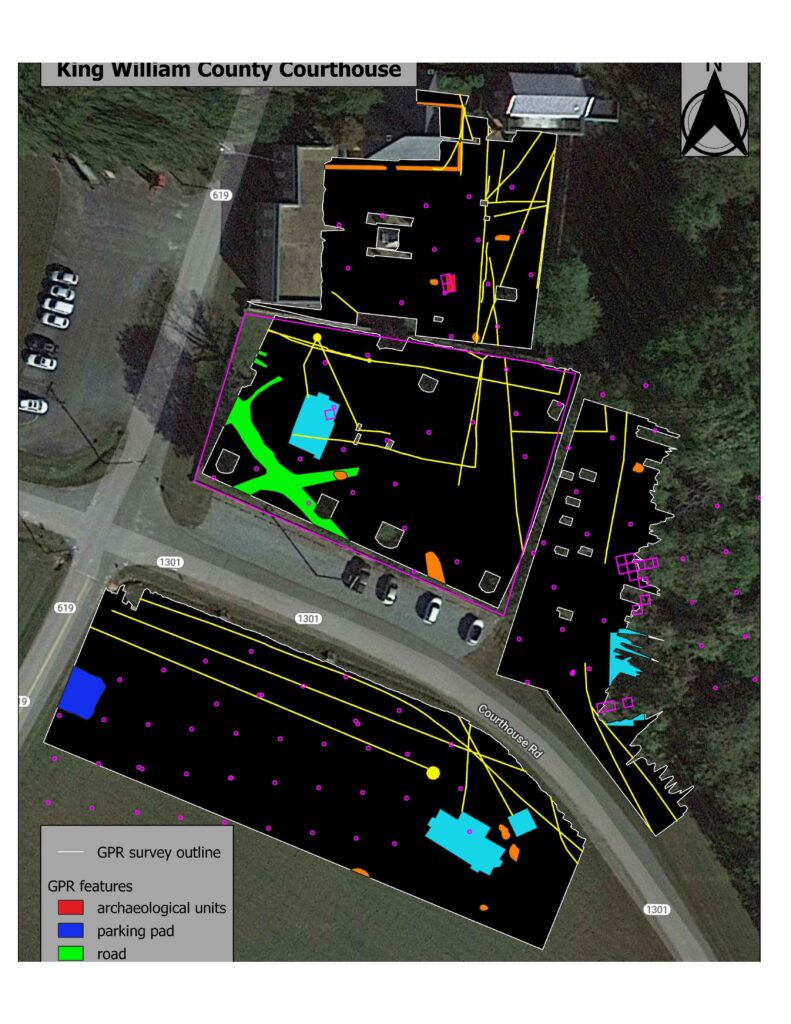

With the ‘blue book’ to guide us, we excavated 114 one-foot-diameter shovel tests on a grid across the property to ‘ground truth’ the document-projected landscape and inform the placement of larger, five-foot-square test units. Using ground penetrating radar (GPR), Bob Chartrand was remarkably successful in defining tavern features beneath the sod, delineating a 40-x-20-foot rectangular brick anomaly as the most likely candidate for Quarles Tavern. The GPR-detected footprint is smaller by 32 feet than the building reported in the Gazette, but the remaining width of the original building may have rested on simple brick piers. Across the site Chartrand found four additional structures through GPR including the clearly visible Hill’s Hotel, with an associated outbuilding across the road south of the tavern, and a possible store south of the clerk’s office whose deep basement was previously encountered by the archaeologists. This work produced a medicine bottle dating the basement fill to after the turn of the 20th century. No photographs of this, or indeed any of the other lost buildings besides the livery stable, have come to light. The GPR survey also identified an ‘X’-shaped anomaly immediately south of the General Store, possibly representing an older crossroads, and a slightly larger feature around the courthouse itself that could potentially be the remains of a still-earlier courthouse or an earlier, more extensive arcade.

Since 2019, Fairfield volunteers have helped dig 21 five-foot-square test units in search of buildings and landscape features at the site of John Quarles’ ‘colonial ordinary’. Our finds include classic tavern artifacts: fragments of thick, dark green wine bottles, stoneware jugs, tankards, pewter, animal bones, oyster shells, and clay tobacco pipes. There were also some surprises. The diversity and quality of the ceramics is scarcely known outside the taverns of colonial-era Williamsburg. King William’s jurists, planters, and plaintiffs supped from Chinese porcelain, decorated delftware, and finely molded English stoneware. Archaeologists rarely find complete ceramics; pieces are generally found scattered between various rubbish dumps, fire pits, or compost piles. When multiple fragments of the same finely-decorated delft dish started appearing in the bottom of one pit, all held their breath. In the end, there emerged the better part of a blue and white delft dish with a Chinese-style garden scene. A near exact match, made in Liverpool and dated 1744, gave us a rare confirmation of the deposit’s minimum age and a wonderful example of the table wares that once served tavern guests. The soil conditions which preserve animal bone intact also yielded remarkable pewter fragments of soft, mellow gray. Some metals, however, don’t suffer from adverse soil conditions. The crew has now found two of what most archaeologists never find in their careers: gold coins. The two five-dollar gold eagles bear the dates 1834 and 1846. How they were lost will remain a mystery. The brilliant, nickel-sized coins were found among the remains of outbuildings north of the tavern. A brass scale weight found close by recalls days before standardized currency when coins of all nations were legal tender and a tavern-keeper relied on weights to reckon his customers’ motley specie.

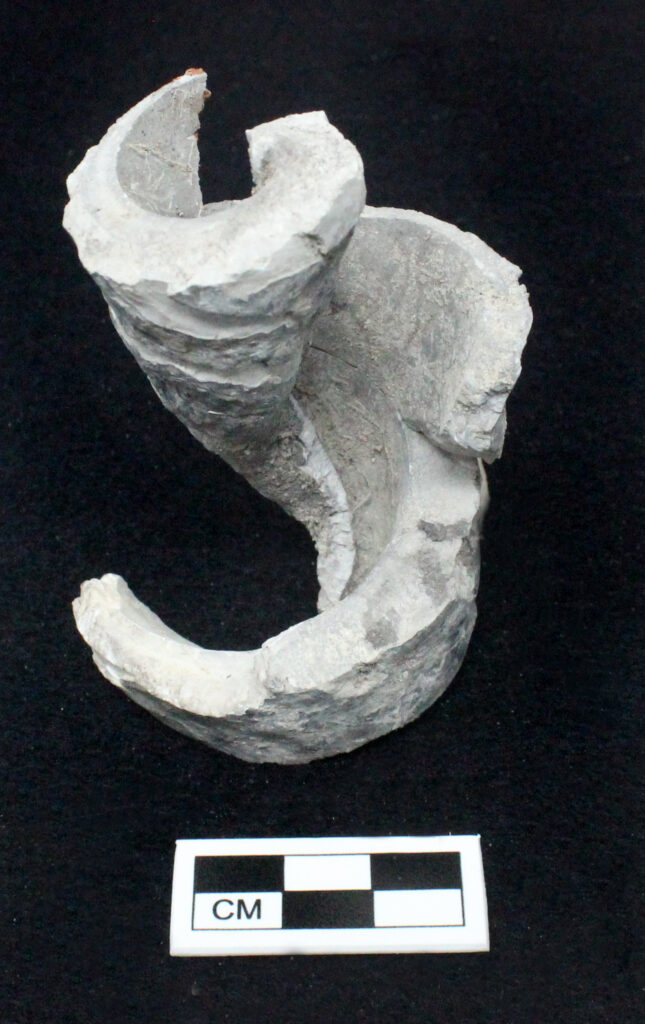

Life at the tavern in the mid-19th century seems underrepresented by the artifacts, possibly reflecting lean years; but the structure was clearly in use at the end of the 1800s. Many of the most evocative artifacts come from the thick layer of greasy charcoal and gray-white ash that marks the building’s fiery destruction before the turn of the 20th century. The test units that encountered this layer opened a near literal window on the southwest corner of the tavern, onto a room with a marble-topped piece of furniture, a carbonized piece of whose woodwork may survive, decorated with lightning and channel whelks. The lack of metal hardware suggests a table or dresser with the wooden handles common to the 1870s-80s. Fragments of decorative pressed glass vessels, bottles, and windowpane abound, many contorted into fantastic shapes as they puddled and dripped among burning timbers. Oddly repetitive circular rust stains were revealed to be the springs of a bed or piece of upholstered furniture. There is even the grip of a red rubber dip pen marked Eagle Pencils.

Under and among the glass, nails, and sugary marble were charcoaled fragments of beams. At the base of the burn layer are the broad, carbon black floorboards of the tavern, still in their original north-south alignment where they fell as the joists burned away beneath them. This whole layer reeks of acrid smoke, un-smelled since the day the rubble was raked together and covered in earth. The surface of the burn layer was scattered with the brass caps of cardboard Remington shotgun shells dating to the late 1890s and, in between, a souvenir badge from the 1896 cornerstone laying of the Jefferson Davis monument in Richmond.

Future excavations will continue to uncover more details about these lost buildings and the changing landscape of King William Courthouse. We are planning continued excavations at the site every second and fourth Thursday through the spring, and we welcome members of the public to visit the site while we are working.

Blog written by Oliver Mueller-Heubach, Staff Archaeologist

Interesting! Another job well done!

Great job, Oliver. Well done!