By Sara Lewis, Development Officer

This blog is part of a series about the Catlett family members buried at Timberneck in Gloucester County.

April 3, 1903″

“Fanny” was the eighth child of Armistead Burwell (1771-1841) and Mary Cole Turnbull (1782-1860) of Dinwiddie County, Virginia. Her parents had 13 children in about 20 years and Fanny grew up with eleven surviving siblings.

Her fourth great grandparents were Lewis Burwell II (1650-1710) and Martha Lear (1668-1704) of Fairfield in Gloucester, whose son and her third great grandfather, Lewis Burwell III (1698 or 9-1744), established the Kingsmill branch of the family in James City County. While the Burwells were known for having large families, Armistead was an only son, his father was a second son, and his grandfather was a third son. He didn’t stand to inherit the wealth of a first born and was less prosperous than some Burwell relations. In fact, Fanny’s father struggled to make ends meet, especially after the Bank Panic of 1819. He sold his 1,000-acre property in Dinwiddie, where most of his children were born . . . and they grew up playing with an equally large number of children born to their father’s enslaved women. He humbled himself in taking a job as a steward at Hampden-Sydney College in Prince Edward County, but soon moved to Boydton, Virginia, to make a new start. He died in 1841 when Fanny was 27.

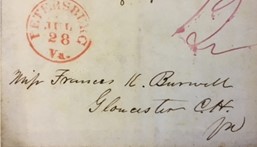

After Armistead Burwell’s death, Fanny, her mother, and Fanny’s youngest sibling, Bettie, lived with an older, married sister, Anne, at Mansfield near Petersburg. By this time, all the other siblings had moved away to other parts of central Virginia, to North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas. Several were teachers, one was a preacher, another was an attorney, one was in the Army, and others headed to Texas to raise cattle and grow cotton. Fanny enjoyed a lively exchange of letters with her siblings, which she saved. They were transcribed and accessioned as the Burwell-Catlett Papers, donated to the College of William and Mary’s Swem Library in the 1960s by Fanny’s great-grandson, Powell Burwell Rogers.

From her correspondence we learn that Fanny’s life changed soon after her father’s death. On March 11, 1842, sister Bettie sent a letter to Fanny at her new address in Gloucester that tells us how. “We are delighted at receiving your letter, and to hear you are so well fixed, and satisfied with your new home. I am really glad to learn your scholars are not dull, there will be satisfaction in teaching them.” Fanny had taken a position as governess for Reverend James Baytop and his wife, Lucy Taliaferro Catlett, of Springfield in Gloucester.

Perhaps one of the most interesting letters to Fanny in the William and Mary collection is from Lizzie (Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly, 1818-1907), a woman who began her life as a slave to the family of Armistead and Mary Burwell. Lizzie wrote a long letter to her half-sister Fanny on April 25, 1842, although they didn’t know about their blood relationship at the time. (On her deathbed, Lizzie’s mother confessed that Armistead Burwell was Lizzie’s father.)

Lizzie’s mother, Mammy Aggy, is believed to have been one of the Burwell family’s most loyal and valuable slaves, inherited by Armistead Burwell from his parents and very likely descended from people enslaved by the Burwells in Williamsburg and, before that, Gloucester. Sometime in the spring of 1817, when Armistead’s wife, Mary, was pregnant with his tenth child, he sought the attention of Aggy, and she had no choice. Later, Mary’s commonplace book, or housewife’s diary, included the entry “Lizzy – child of Aggy/Feby1818.” Aggy was allowed to bring Lizzie into the Burwell’s home and four-year-old Fanny made Lizzie her “special pet.”

By the time Lizzie wrote to Fanny at the age of 24, she had been “loaned” around to other family members, raped while on loan to Robert Burwell in North Carolina, and had a son. To learn more about the life of Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly, see the Burwell School website that includes part of a PBS documentary on this remarkable woman who would later be Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress and confidant. The Burwell School was founded by Robert Burwell’s wife.

Lizzie’s letter to Fanny was written from Anne’s home near Petersburg, where she was loaned after the situation in North Carolina deteriorated. It was full of news about family, neighbors, events, and upcoming marriages among the white family and friends. Her sentences also subtly reveal the involuntary nature of the duties she performed as a house slave. “In your letter to Miss Betty you said that you were expecting a letter from me,” wrote Lizzie. “I guess you will not be surprised when you receive this . . . I am very busy making shirts. I have had to stop two or three days to cook as the women are chopping corn. I have got to make Miss Bet’s frock to wear to Miss Betty Scotts wedding . . . Every one of the servants send their Love to you, Mammy in particular, and also all of the white people, little and big.”

Although Fanny’s mother schemed for her to come back to Petersburg and set up a school with her and Bettie, Fanny didn’t reply, much to her mother’s dismay. In a letter to Fanny written on June 12, 1844, her mother writes curtly, “. . . it was with feelings of the deepest interest that I received from yourself the intelligence that you had made choice of one in whom you can place your affection . . . it is a most responsible station the one in which you are about to enter, that of wife and mother . . . I had heard that you were going to be married and all that I could say was that I had not been apprised of it by you: and had felt a little uneasy at not getting a letter from you for so long a time.” Fanny was to marry Lucy Taliaferro Catlett Baytop’s brother, the widower John Walker Carter Catlett.

Fanny’s brother, Armistead Burwell, an attorney in Vicksburg, Mississippi, sent her a topaz he brought from Texas or Mexico and made into a brooch to wear at her wedding. None of the letters indicate that her mother or any of Fanny’s siblings attended the wedding. By 1850, her mother was living in Mississippi with her son and his family.

John W.C. and Fanny Catlett’s household included three girls and two boys by his first wife, Agnes Thruston. Fanny’s first child, Charles, was born July 12, 1845. William was born in 1847, Mary in 1850, Hettie in 1852, Powell in 1854, and Landon in 1857. The Catletts enslaved 45 people by 1860, but Fanny’s life was surely hectic despite the involuntary involvement of enslaved people in many tasks. Fanny’s mother was unsympathetic to her situation, and she frequently complained that her daughter had not written in a long time. She said, “every letter I get from any [of your siblings] they say they think hard of your not letting them ever hear from you.” In another letter she said she “heard indirectly that you had a daughter. I could not help feeling mortified that Mr. Catlett had not apprised me of it.” Remarkably, Fanny’s mother’s letters also indicate that Aggy, the enslaved woman who had had a child with her husband, was still Mary’s “servant” at her son’s home in Mississippi.

When John W.C. Catlett was in Richmond as a state senator, he also complained that Fanny would not write often enough to suit him. “Why my Dearest have you not written: William Baytop came very unexpectedly to see me on Friday night and informed me that you were at a party as lively as a lark: He did not even bring me your love until I asked him if you sent me no message: I was pleased to hear you were at the party for it afford me much pleasure to know that you are well and enjoying life: May God in his mercy never visit you with misfortune.”

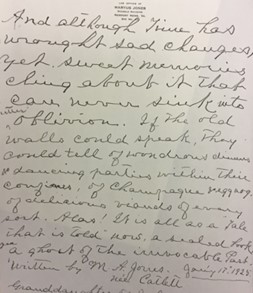

The letters became less frequent with the years. Fanny’s mother died in 1860 and was buried in Vicksburg. It is not clear from the correspondence whether she ever made it to Timberneck, although her letters do say to give her love to friends in Gloucester. It is clear, however, that Fanny’s daughter, Mary Armistead Catlett Jones (1850-1933), had fond memories of her mother, her family and friends, and growing up at Timberneck. She wrote essays for her children that are included in the Burwell-Catlett Papers.

The parties at Timberneck Mary described must have been legendary and Fanny a cheerful hostess. Crowds of guests danced to fiddle music on the first floor and had supper of ham, mutton, oysters, and more on the second. Because they danced, ate, and were merry, it wasn’t unusual for guests to stay the night rather than take horses and carriages home in the dark. “My mother told me she had breakfasted as many as forty people after a party,” said Mary Jones in her story, “Gloucester in Other Days.” Fanny must have been quite fun . . . lively as a lark, indeed.

Sources

Burwell-Catlett Papers, 1794-1887

Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly 1818-1907

Burwell School Historic Site. https://burwell-school-historic-site.square.site/elizabeth-keckly

Fleischner, Jennifer (2003)

Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship between a First Lady and a FormerSlave. Broadway Books

U.S. Census Records, 1840, 1850, and 1860 population and slave schedules.

Another excellent story. Interesting how so many historic families intertwined.

WOW…Sara…….SUPERBLY DONE !!!!!

I will have to read this multiple times to digest the great information you have here.

This gives me a completely different and more educated perspective on the people who lived and died at Timberneck. The house will become more alive to me than ever.

THANK YOU !!!

Tom