Sara E. Lewis, Development Officer, Fairfield Foundation

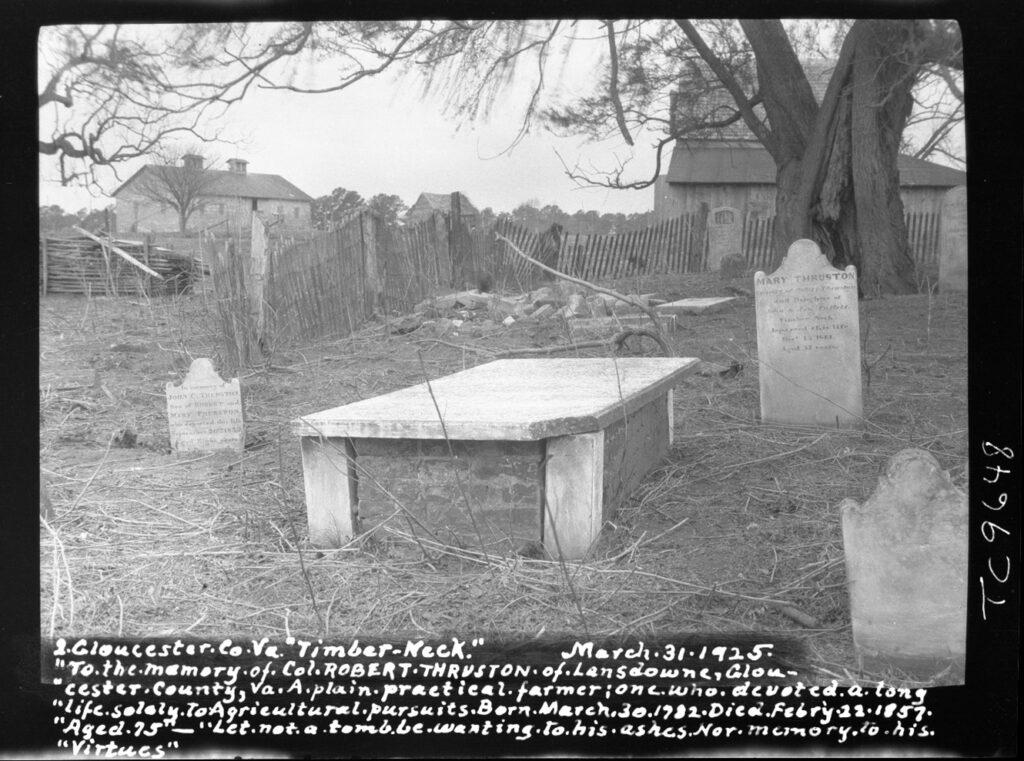

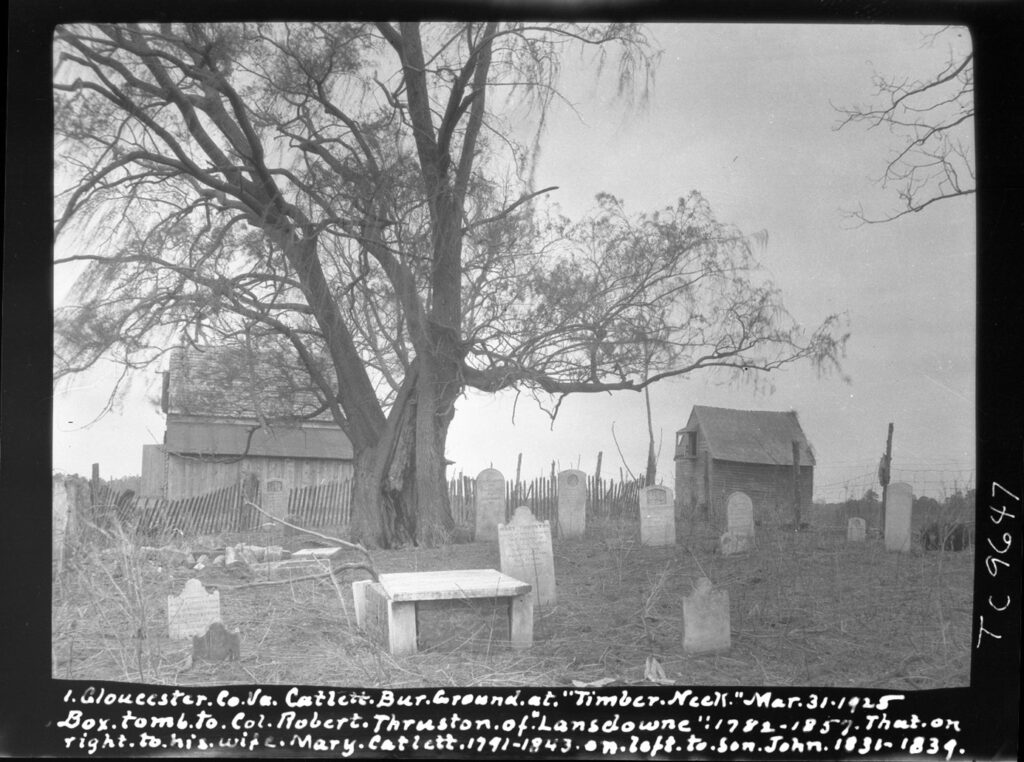

The headstone of John Thruston (1831-1839), who died at the age of eight, is the oldest surviving memorial in the Catlett family cemetery at Timberneck. The second oldest is his mother’s, Mary Catlett Thruston (1791-1843). The table tomb of Col. Robert Thruston (1782-1857), father and husband to John and Mary, respectively, is the fourth oldest.

Robert’s tomb inscription says he was “A plain, practical farmer, one who devoted a long life solely to agricultural pursuits” and this seems to be true. There is little other documentation, neither letters nor lore, to add colorful stories to illuminate his or his immediate family’s lives. Even so, genealogical research and historical documents, such as census records, encourage the following deductions explaining what brought these three Thrustons to rest in the Catlett family cemetery at Timberneck, rather than at their home, which was customary before the mid-19th century.

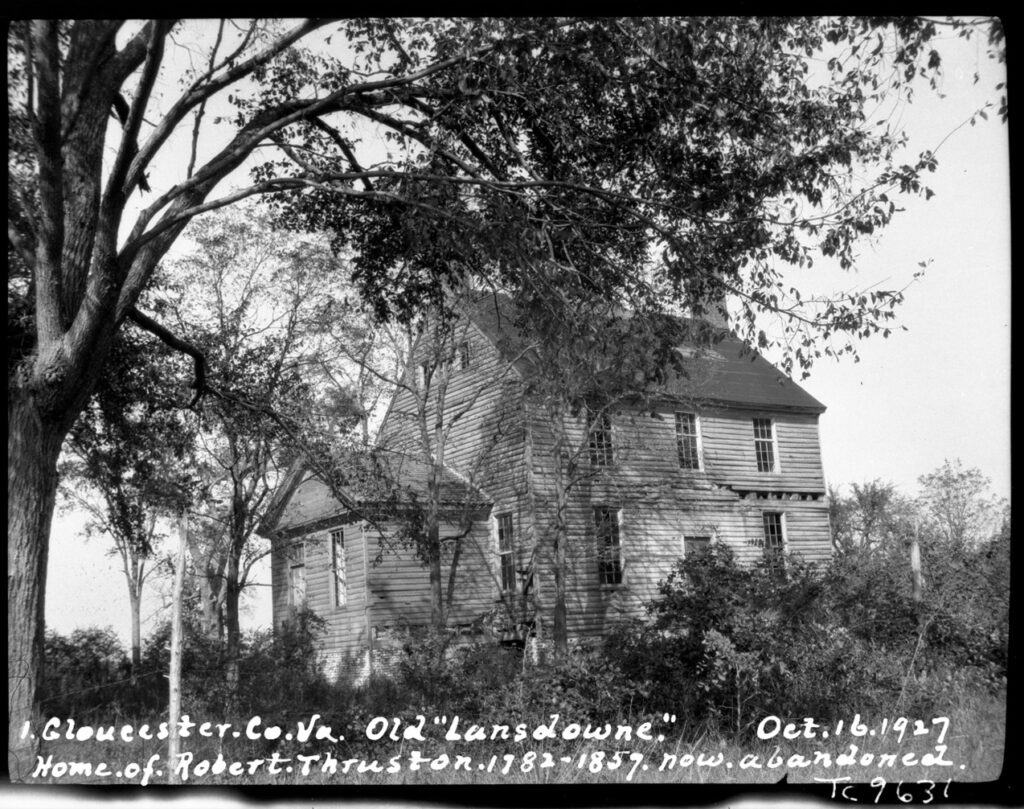

Landsdown[i] was a two-story frame house on a brick foundation. It was probably built sometime after Robert’s grandfather, John Thruston (1709-1766), signed a marriage contract on November 30, 1737, stating that “I John Thruston of York town am held and firmly bound unto Sarah Haynes of Gloucester Town.” Formerly Sarah Mynn (1716-1786), John’s betrothed had been bequeathed land in Hertfordshire, England and York County, Virginia. Sarah’s baptism, marriages, and burial are captured in the Abingdon Parish Register. Apparently quite the catch, young Sarah had been married briefly twice before to much older men. In choosing Sarah for his wife, Robert Thruston’s grandfather had married well.

Landsdown was built on low, fertile ground off the Severn River to the northeast of Timberneck. The late Georgian/Federal style of the house leads us to believe that either the second-generation John Thruston (1750-1782) and his wife, who was also named Sarah (Stevenson), had Landsdown constructed, perhaps in the third quarter of the 1700s, or it was built for their son, Robert.[ii]

Robert was born on March 30, 1782, an only child whose father died the year he was born. His mother died about 1800, so mother and son may have lived with an aunt or uncle.[iii] In 1787, when Robert was five years old, his uncle, Robert Thruston (1759-1816), the youngest of his aunts and uncles, bought Carter’s Creek (Fairfield) and 500 acres for £1500 from 23-year-old Lewis Burwell (1764-1833).[iv]

According to a Thruston family Bible, Rev. Armistead Smith united Robert Thruston of Landsdown and Sarah Brown in holy matrimony on December 22, 1804, at Belle Farm. The couple had five children before Robert served in Gloucester’s 21st Regiment of Virginia Militia from 1813 to 1815 during the War of 1812. Afterward, Sarah gave birth to a sixth child, a son, before she died in 1818. Then, in a household without a wife or mother, it fell to Robert’s four girls, Ann, Agnes, Sarah, and Eleanor, ages 8 to 13, to care for their younger brothers, William and Edward, ages 5 and 1. Enslaved people at Landsdown certainly were tasked with caring for the household, too.

Soon, however, they had help. Robert Thruston married his second wife, Mary Catlett (1791-1843) of Timberneck on December 20, 1820. When she arrived, 1820 U.S. Census records tell us there were 5 white males, 3 white females, and 32 enslaved people at Landsdown. Mary added two daughters to the family in 1824 and 1827. As was customary, they may have been born at her childhood home, Timberneck, where Mary’s sisters and stepdaughters could have attended her.

On July 6, 1826, Robert Thruston’s second-eldest daughter by his first wife, 20-year-old Agnes Jane Thruston (1806-1838), married Mary’s brother, Timberneck’s prosperous young inheritor, John Walker Carter Catlett (1803-1883). By marrying Mary’s brother, Agnes became Mary’s sister-in-law, in addition to being her stepdaughter.

Ann Thruston (1805-1836), the eldest daughter of Robert and Sarah Thruston, also married into the extended Catlett clan about this time. She became the second wife of Mary’s sister’s husband, Christopher Staat Morriss (1797-1851), who was the much younger husband to Mary’ sister Matilda Catlett (1780-1819). Ann and Christopher lived at West End in Gloucester. Ann died young, probably during or after childbirth, and the twice-widowed Morriss bought land in Mississippi. He left Virginia with their daughter and overseer to seek his fortune in Deep South cotton.[v]

Stepmother and sister-in-law Mary probably oversaw the birth of John W.C. and Agnes Catlett’s first two children in the late 1820s. By 1830, the Catlett household at Timberneck included 2 white males (John and his bachelor brother) and 3 white females (Agnes and the babies). Eighteen people were enslaved by the Catletts to work in their home and in the fields. In the same year, at Robert Thruston’s Landsdown there were 3 white men, 5 white women, and 35 enslaved people. Then, in 1831, both sisters-in-law, Mary and Agnes, gave birth to children: John and Charity were each woman’s third child.

The Catlett and Thruston families suffered a series of personal losses in the 1830s.[vi] Charity Catlett died in 1833. After the birth of two more sons, Agnes Jane Thruston Catlett died in 1838. The Thruston’s son, John, died at eight years of age in 1839. He was laid to rest in the cemetery behind Timberneck house, the earliest marked grave known in the Catlett family cemetery. Might his cousin Charity and Aunt Agnes have been interred nearby, in graves that have since lost their markers?

Next, tragedy struck when Mary Catlett Thruston died in 1843. In the five-year interim between her stepdaughter/sister-in-law Agnes’s death and her own, Mary may have provided comfort and structure to the Timberneck household which included four children. The youngest was born in 1838 and may have been the cause of Agnes’ death. William Thruston Catlett, born in 1838, died three years later in 1841. Before and after Agnes’s death, Mary may have brought her three children and up to four stepchildren to Timberneck when she visited. There, the Catlett and Thruston children, up to 12 cousins, were playmates and household helpers.

Dec. 1st, 1843/ Aged 52 years”.

After Mary’s death, the Timberneck household surely grew quiet. The Catlett children once again needed a mothering influence. Widower John W. C. Catlett quickly remarried in 1844. At Landsdown, Robert did not marry again. In 1840 when Mary was still alive, their household included 5 teenaged and young adult children who perhaps needed little mothering. Thirty-seven slaves were necessary to maintain the household and fields for this “plain, practical farmer.” When the 1850 census was taken, 69-year-old Robert enslaved only five people to care for his household. Robert and Mary’s daughter, Sarah, now 23 years old, still lived with her father. So did 60-year-old Sarah Stubblefield, whose role in the household is not defined by the census. His son Edward and wife Julia, with their four children, lived in the household following Landsdown as listed in the U.S. Census, so probably next door.

On February 10, 1857, Robert’s brother-in-law John W. C. Catlett wrote in his ledger: “I came from Colo Thruston’s today, he is still alive but as low as he well can be.” After another visit nearly two weeks later, on February 23, he wrote that “Colo Thruston” had expired the evening before “after a most tedious and painfull spell of more than two months.” He was less than a month short of his 75th birthday.

On February 24, Robert was laid to rest between his wife and son in the Catlett family cemetery at Timberneck. “He was attended by a respectable number of friends,” said his brother-in-law. “His children & servants[vii] are much distressed.” Perhaps the man, who was once an only child, preferred the lively site of his second wife’s happy years for his interment.

(Filson Club Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky).

[i] Landsdown is how the home name appears on the tombstone from 1857; it is also spelled Lansdown in Gloucester’s Land Tax records. In the 1917 publication “Colonial families of the United States of America, in which is given the history, genealogy and armorial bearings of colonial families who settled in the American colonies from . . . 1607, to . . . 1775” George Norbury Mackenzie (1851-1919), editor, it is noted that “Lansdown” is the name of John Thruston’s (1709-1766) home in Gloucester. I have used Landsdown to match the tombstone inscription.

[ii] However, we don’t know much about Landsdown. A brief land tax search found Robert Thruston owning it from 1811 through his death (part of the Brew house tract), but it is unclear who has it before 1811 and it does not appear to be Thruston land then. More research is needed. There is building value listed in 1820, which suggests the house is at least this old.

[iii] Robert’s father was one of possibly 10 children of John and Sara Mynn Thruston, of whom four or five were living in 1782.

[iv] His second great grandfather Lewis Burwell (1650-1711) had overseen the building of Fairfield nearly 100 years earlier.

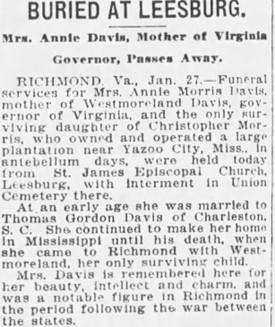

[v] The family would become wealthy as cotton planters. Robert Thruston’s granddaughter, Ann Morriss (1836-1921), married Thomas G. Davis (1832-1860), who moved to Mississippi from South Carolina in the 1850s. By the time of his death in 1860, he enslaved 202 people on his Palmetto Home plantation near Yazoo City, Mississippi. Ann and her son, Westmoreland D. Davis, (1859-1942) moved to Richmond, Virginia, during the Civil War. Westmoreland Davis was a lawyer and agriculturalist who published the Southern Planter magazine from 1912-1942. He served as a Democratic Governor of Virginia, who identified with the Progressive movement, from 1918-1922.

[vi] During these busy years, both John W. C. Catlett and Robert Thruston participated in Gloucester’s Jacksonian political caucus that led to the election of Andrew Jackson as president. They continued to support his Vice President, Martin Van Buren, in his run for President. The so-called Jacksonian movement championed suffrage for the common man, not just landowners, and the restructuring of the federal government to give more rights to individuals. Historians point out that these seemingly egalitarian ideals were quite limited, as the case for greater democracy was for white men only. However, it marks the beginning of the expansion of voting rights in the U.S.

[vii] In his ledgers, John W.C. Catlett referred to enslaved people as “hands” or “servants.”

This is quite interesting. I didn’t know about the additional house. It’s a good illustration of the shortness of life in those times and the multiple marriages across households. It’s also a reminder that “plain folk” relied economically on slavery as well. I wish we knew more about those folks. I’ve always assumed that the many people of slave heritage who are named Catlett. Can well be my relatives too.

Thanks, Kitty! This was interesting to research. Hope all is well with you.

Thank you for the excellent genealogy. I always wondered why one stone was marked Thurston. Glad to know it was a misspelling of Thruston.

Thanks, Ann! I think some of the stones are replacements/later additions, so perhaps it may have happened when someone was “straightening up.” For example, William Burwell Catlett’s is suspicious because of the willow tree iconography. That imagery wasn’t used until the turn of the century. Also, it matches Powell Burwell Catlett’s headstone and they died 30 years apart.