Written by Sara Lewis, Development Officer

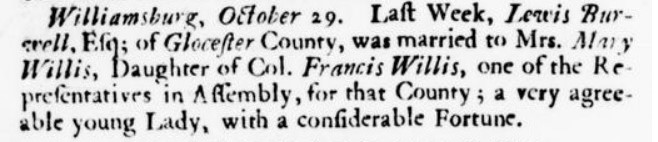

On a fall day in 1736, when Lewis Burwell (1711/12-1756) married Mary Willis (1718-1746), it may have been crisp and sunny with orange-yellow leaves rustling under foot, a day not unlike today. Although we don’t know exactly where the nuptials took place, we can imagine that they were as grand as possible, given the customs of the times and the family’s wealth. The marriage was between two young people who had ascended to the pinnacle of the Virginia gentry class, and would soon have their portraits painted, as was customary among their peers.

According to an announcement in the Virginia Gazette:

They lived at Fairfield Plantation, built largely with the labor of the enslaved people owned by their Burwell grandparents in 1694. It was one of the largest and most grand houses of its day. Although it burned to the ground in 1897, the Fairfield Foundation knows a lot about the Burwell family’s wealth from archaeological research. Along with systematic excavations, the Foundation’s archaeologists use written records, oral traditions, folkways, and other evidence to make sense of the past and to tell the stories of those who came before us.

By the time Lewis and Mary were married, her mother, Ann Rich Willis, had died. It is likely that she was one of the sources of her daughter’s considerable fortune. Ann was born about 1695, the daughter of Edward Rich of London. She is mentioned in her uncle Elias Rich’s will, proved in England in 1719, which also mentions Edward as his deceased brother. Elias surely felt responsible for his niece since he placed property “in Broad Street, near the Royal Exchange, and all other my freehold messuages, lands, &c.” in trust to provide an income to Ann during her lifetime. Afterwards, the property descended to her three children, among whom was Mary Willis Burwell. Ann was described in her uncle’s will as the “wife of Mr. Francis Willis, a Virginia planter.” Daughter Mary Willis also inherited Purton plantation on the York River after the death of John Smith (1685-1712), her step grandfather. Elizabeth Smith Harrison Willis, her stepmother, was Smith’s daughter, and Francis Willis’s second wife.

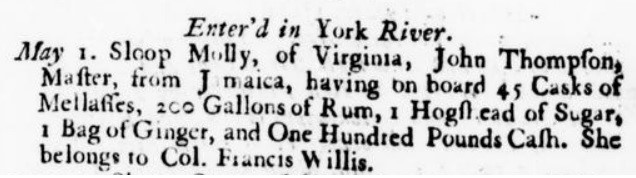

Mary’s father, Francis Willis (1689-1769), had inherited land in Gloucester from an uncle and is believed to have built the first house on the Ware River site that became the Willis family ancestral home (later White Hall on the Ware River in Zanoni). The Virginia Gazette provides advertisements for his business as a merchant, participating in the triangular trade between the Americas, Europe, and Africa for commodities, money, and slaves, such as this one from 1738:

Mary’s husband, Lewis Burwell, was also wealthy, as the eldest of the fourth generation of Virginia Burwells. His father, Nathaniel Burwell (1681-1720), and grandfather, Robert “King” Carter (1662/63-1732), were among the colony’s wealthiest landowners, slaveholders, and planters. His father died before he was 10, though, and his grandfather stepped in to secure the future of his grandchildren by his daughter Elizabeth Carter Burwell (1692-1734). Lewis was sent to school in England, to Eton and then Cambridge. After his grandfather’s death, Lewis’s responsibilities and inheritance increased. In 1734, two years before his marriage to Mary, he wrote to a friend in England, “I have had the misfortune to lose my Mother since I return’d to Virginia whereby my Estate is pretty much increasd; the greatest part of her dower falling to me . . .” As oldest son, he inherited his parent’s large manor on Carter’s Creek.

Portraits of Lewis and Mary were made at some point during their decade-long marriage. According to the provenance recorded by the Frick Art Library, they were painted by Charles Bridges, an English portrait artist who worked in Williamsburg from 1735 to 1744. However, a more recent study by Janine Yorimoto Boldt appearing as a website, Colonial Virginia Portraits, and produced in collaboration with the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, notes “For many years, many paintings from Virginia dating to the early to mid-eighteenth century were attributed to Bridges based almost entirely on the fact that he was one of the only documented portraitists working in the colony in that period. Many of these attributions are incorrect and are now considered works of unknown artists based on stylistic differences from Bridges’s signed works.” By this means, Boldt attributes Lewis and Mary Burwell’s portraits to an English portrait artist whose identity is currently unknown.

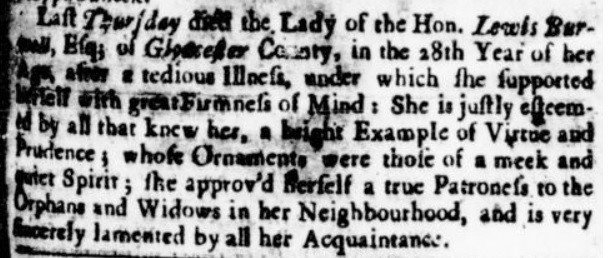

Lewis and Mary soon had their first child, a son, Lewis Burwell (1737-1779). Daughter Elizabeth was born in 1739 and another daughter, Anne, was born in 1741. A third daughter, Mary, was born in 1744. A final child, Rebecca, was born in May 1746. On May 29, 1746, the following announcement appeared in the Virginia Gazette.

By the time of Mary’s death, Lewis Burwell had risen from a position as an elected member of the Virginia House of Burgesses to an appointment on the Governor’s Council. He became the senior member of Council in 1750 and served as acting Governor for about a year while the Governor and Lieutenant Governor were absent from Virginia. At the November 21, 1750, Council meeting held at his home in Gloucester he said, “I hope my very ill State of Health will Sufficiently plead my Excuse, for giving you the trouble of meeting here . . .” By 1756, a letter by Landon Carter noted that Lewis Burwell had fallen into a reverie, or an altered state of mind. Burwell’s brother, Carter Burwell of Carter’s Grove Plantation in James City County, had also fallen into an illness that alarmed his friends. Both men died within the year.

The children of Lewis and Mary Burwell were still young and went to live with their Page family relatives, who also descended from Robert “King” Carter. For reasons unknown, perhaps because the Burwell manor was unoccupied or that Lewis and his brother Carter were close, the portraits of Lewis and Mary Burwell made their way to the family of his brother at Carter’s Grove. From there, the Frick’s provenance places the portraits with the family of a Burwell wife’s second husband, then his niece, and then in the hands of a New York City art dealer. By some means, perhaps a contact by the art dealer, Lewis and Mary Burwell’s third-great granddaughter, Mrs. William T. Reed, Sr. (Alice Lewis Burwell) of Richmond, Virginia, acquired the portraits in New York. The portrait of Lewis was inherited by Reed’s son and the portrait of Mary was inherited by her daughter.

After sleuthing through genealogies, census records, and newspapers, the portrait of Mary Willis Burwell was found on Zillow.com, where the family home was offered for sale. Through acquaintances, an introduction was made to Christie Reed Smith, Lewis and Mary Burwell’s sixth-great granddaughter, who with her brothers has donated the portrait to the Fairfield Foundation.

The Foundation is thrilled to welcome Mary Willis Burwell’s portrait home again, safe after nearly 300 years of travel and possibly ten different owners. Staff and experts will continue to examine the portrait, its provenance, and its connections. Mary’s life was short but connected in many ways to the Virginia gentry as well as those who were formerly enslaved at Fairfield, who likely tended to her during her life, and in her final days. Her short life was connected to the story of the roles of Virginia women and plantation life, and highlights the extreme contrasts that existed between the gentry and the enslaved African men and women who labored for them. Mary Willis Burwell’s portrait puts a face with a name that will make the story resonate with many who are invited to learn more about the life and legacy of a Virginia plantation as they engage in archaeology research and educational opportunities with us.

Excellent and exciting history! Fairfield Foundation continues to rule.

How delighted I am that the painting of Mary Willis Burwell is home again where she belongs. Congratulations!

Thank you, Tracy!

Sara

What a delightful find. Good job!

Congratulations on the return of a real treasure!

Thanks, too, for such a fact-filled article that’s so readable as well as interesting. Sara Lewis always does a great job. Many thanks to all.