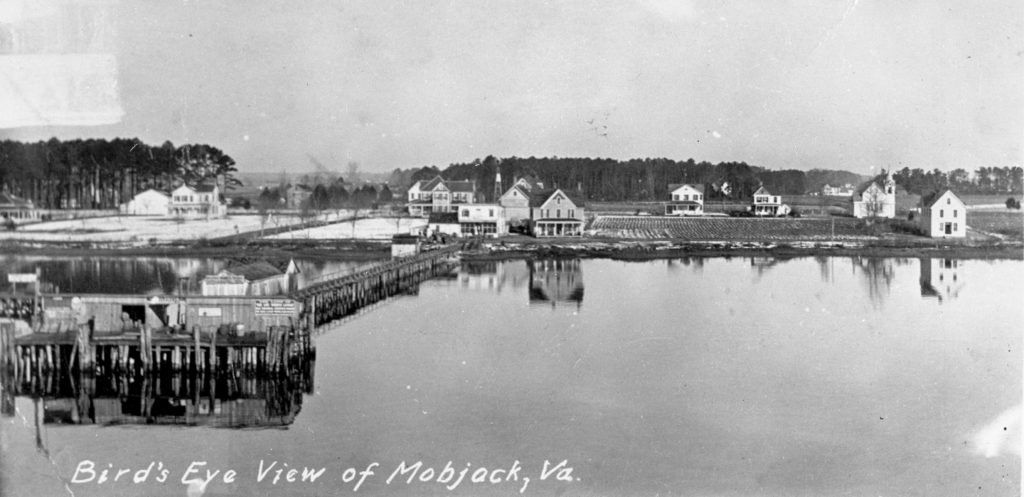

Mobjack ca. 1910 (Gloucester-Mathews Gazette-Journal)

One of the best parts of our work is the idea that you can discover something new and exciting every day. Most of you see this excitement from our archaeological excavations, and if you visit our facebook page you can see how frequent these discoveries occur. But there are other discoveries to be had, ranging from fascinating oral histories and hidden gems in the archives to the architectural fabric of the Middle Peninsula. We are not necessarily the first to discover these precious places, but our introduction to them certainly fills us with joy and excitement. Stumbling upon the beautiful fishing village of Mobjack in Mathews County is a great case in point.

You arrive in Mobjack along an unassuming road after passing an old country store and driving along a tree-lined lane with views of agricultural fields and the East River in the distance. The first surprise is seeing a concentration of magnificent early 20th-century buildings of all shapes and sizes, including a church, country store, dock, and marina. The small lots and gridded street plan contrast strongly with the surrounding agricultural landscape, suggesting there is more to this community’s story than first meets the eye. Mobjack Bay extends off into the hazy horizon, and the reason for the village appears clear – these are the homes of watermen, entrepreneurs, and their families. The surrounding waters are the lifeblood of this quiet place.

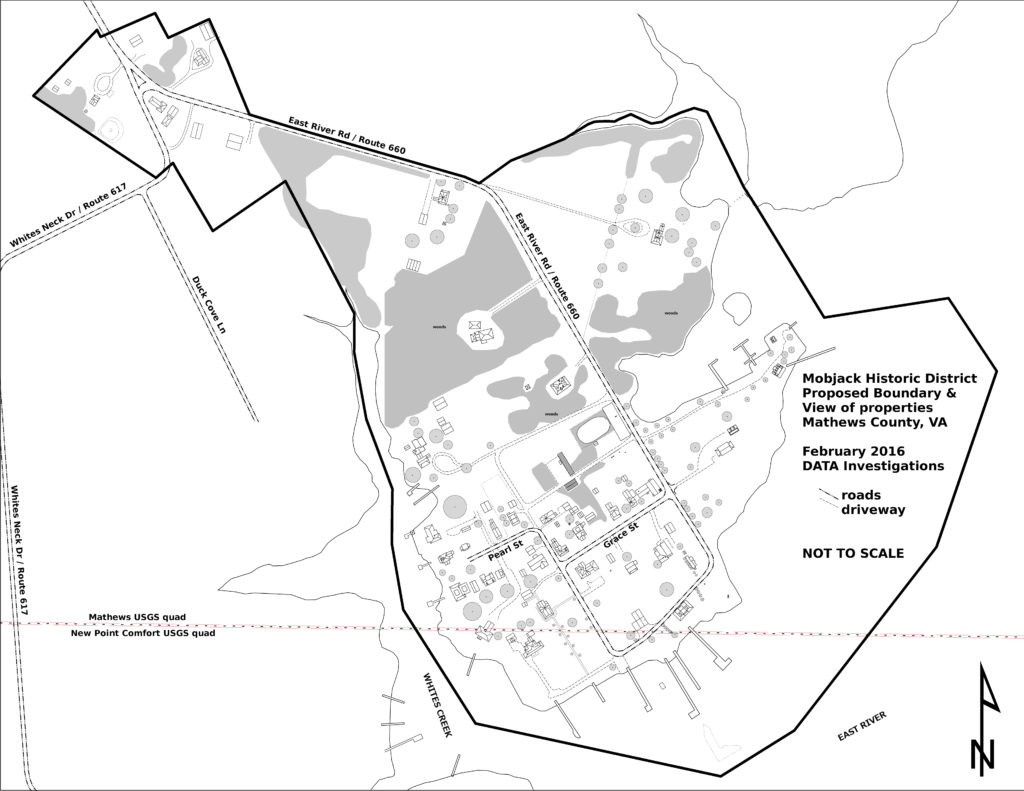

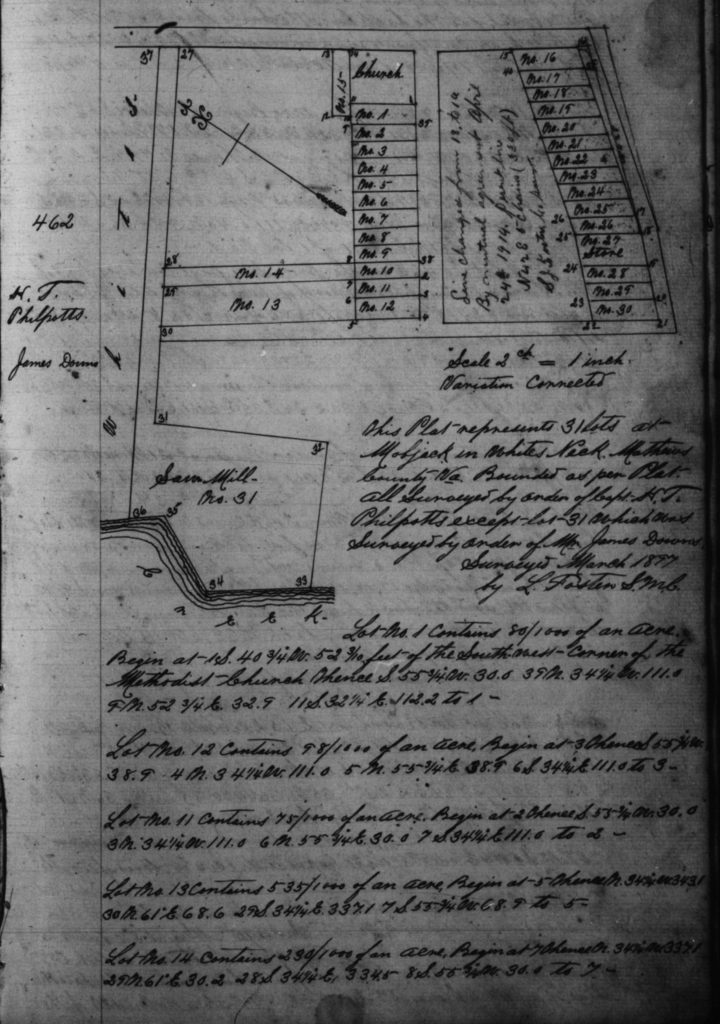

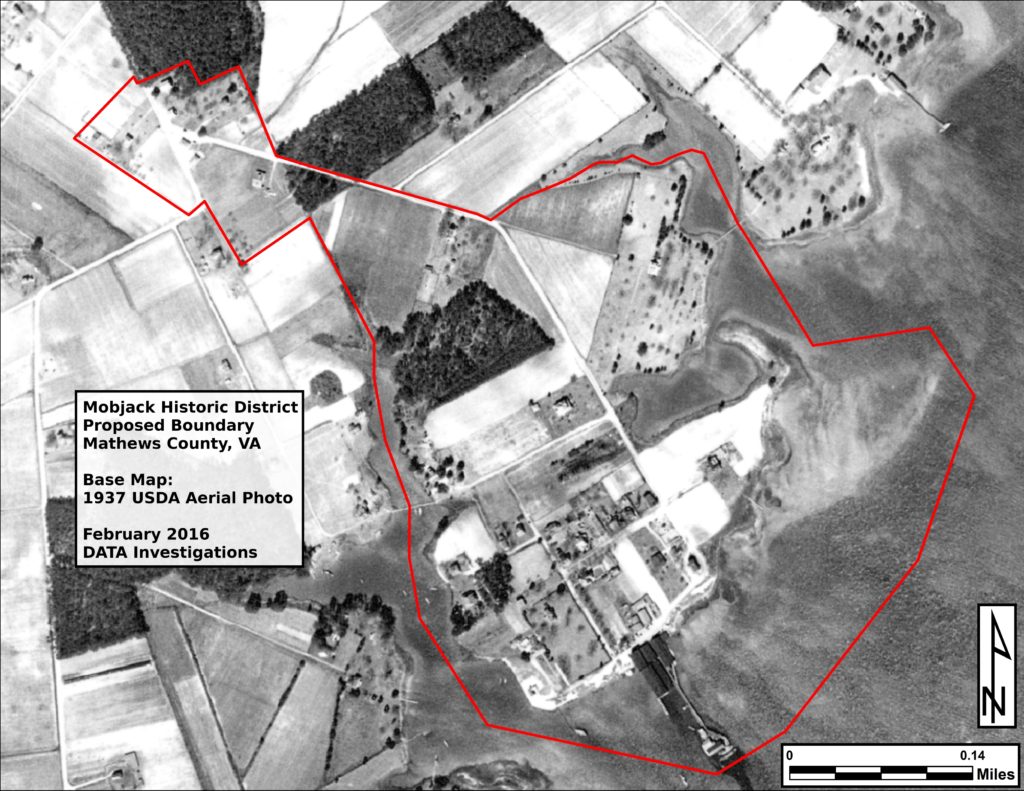

Plat of Mobjack, 1897 (Mathews County Clerk’s Office)

This is much more here than just a collection of buildings. This organized village is a testament to the investments made by Hezekiah Philpotts in the late 19th century, who acquired the land, laid out the town grid, and sold timber to those who purchased lots (from his partner’s saw mill, located on the edge of town). It is a testament to the prosperity of the area in the early 20th century, when a life focused on fishing, crabbing, and clamming could not only sustain a family, but lead to significant wealth. The town was never in the “middle of nowhere” as the steamers of the Chesapeake Bay line connected it with the urban centers of the mid-Atlantic more easily than any road, providing great markets for the bountiful seafood industry. And even the loss of the steamers in the second quarter of the 20th century didn’t deter the community from pushing forward, as docks turned industrial, bringing in oil and, in the case of Mobjack, refining it in their waterside warehouses for resale to county residents. Much of the credit for the prosperity in the village during this period can be given to George Philpotts, son of Hezekiah, who alongside the Machens, Fosters, Walkers, and Andertons, among others, continued to diversify investments while maintaining strong ties to the water and its many resources.

Grace Street, looking west (2015)

Two of the more fascinating stories that long-time residents John Machen Sr. and Ralph Anderton shared with us during our research focused on Mr. Philpott’s economic endeavors. Who would have thought that organic starfish fertilizer would have been a profitable business in mid-20th-century Mobjack? George Philpotts, that’s who! After an unusual infestation of starfish nearly overwhelmed many of the crabbers in Mobjack Bay, George decided to make lemonade from these five-legged “lemons,” harvesting them by the barrel, drying them in industrial dryers, and grinding them into fertilizer. The experiment was short-lived though, as a horrible stink resulted from the processing, and the prevailing winds whisked the noxious smells across the East River to Mr. Hollerith’s farm at Brighton. Suffice to say, Mr. Hollerith was not happy and had the resources to shut down Philpott’s operation. In contrast, a far less odoriferous endeavor involved pickled herring. Similar to the starfish “opportunity,” George Philpotts converted some of his seafood operation to pickling in response to increased demand and profitability associated with exporting this commodity to cities and other inland areas. George brought in a man from India (via his previous residence of Milwaukee) to run the operation, which included several large tanks in his warehouses on the piers extending out into the bay. Mr. Machen remembered taking samples from these tanks, learning quickly that you avoided the herring in the first container, and rarely took any from the second, but the final tanks held such tender and succulent fish that he could hardly resist them, consuming one after the other on those hot summer days.

Grace Providence Methodist Church (2015)

Our recent work at Mobjack concluded earlier this year with the preparation of a Preliminary Information Form for the Mobjack Historic District. This report, filed with the state, was recently approved by the Historic Resources Review Board, confirming that the district is eligible for the Virginia Historic Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places. This designation will hopefully lead to a full nomination of the district in the future, but for now it documents and acknowledges he significance of this beautiful fishing village in Mathews, and its place in Virginia history, by drawing attention to its unpretentious and honest collection of buildings and stories.

I looked for this post on your Facebook page, as I want to share it to Mariner’s Legacy’s page. We have guests that will be riding in the Tour de Chesapeake and it’s a great article to share.

Thank you for this tidbit of Mobjack history. As a recent owner of a Mobjack home, I am very interested in learning more about this extremely fascinating town.

Thanks for the comment. We would love to share more about the fascinating town of Mobjack with you. Feel free to email us at fairfield@fairfieldfoundation.org.

We have traced the Coleman family bloodline to Mobjack Bay .

Robert Coleman and his son Daniel are our ancestors. We know that Robert Coleman arrived in 1638 from Essex England. Do you know where I can find more information about the Coleman family of Mobjack bay ? We have used the usual internet sources.