In August, The Fairfield Foundation wrapped up interviews for an oral history project directed by University of Florida graduate student Jessica Taylor, aimed at recording oral histories about the Edge Hill Service Station and Gloucester’s Main Street community. What struck Jessica as a common thread through many of the interviews was the interplay between the spread of automobiles within the community and beyond and the social experiences of Gloucester’s youth. In the following guest blog, Jessica shares with us some amusing and heartwarming moments from the interviews, as well as her thoughts about the influence of cars on the intricacies of courtship in Gloucester County.

In my couple of wonderful weeks spent interviewing folks in Gloucester, thunderous and laughing Ronnie Stubblefield was only my second or third out of twenty-five interviews. It’s safe to say that I didn’t know Gloucester natives well enough when I reacted in disbelief to Ronnie’s honesty about his wild days in the late fifties:

JT: Okay. If you had a car in high school, or if you knew someone that had a car in high school, what do you do on a Friday night?

RS: Let’s see. We used to cruise for chicks.

JT: No.

RS: It’s the truth I’m telling. [RS laughs] You always had to. Most of the time it was fruitless, you know? [JT laughs] “Hey, where are the chicks?” We didn’t know where to look, [JT laughs] which was probably a good thing. You can understand I’m being truthful about this.

JT: No. I love it. [RS laughs]

RS: We always would go somewhere. It’s like, go to Mathews, you know. You always hear, “Hey, there are plenty of chicks in Mathews.”

JT: Where? On the side of the road?

RS: No.

JT: Okay.

RS: You had a little restaurant over there, right next to Donk’s Theater… Yes. You’d go over there. Of course, after you got over there, no chicks. [JT laughs] Or they were taken. Whatever, you know. That’s part of evolution, part of growing up.

My fascination with Ronnie Stubblefield’s horribly misinformed (and inefficient) dating strategies gave way to a deeper fascination with what now appears to be everyone’s dating strategy. Andy James Jr. fessed up:

JT: You were a student athlete. What does a student athlete do with their car on a Saturday night when there’s no football game?

AJ: Go find the prettiest girl you can find and take her for a ride. [AJ laughs]

JT: That’s what Ronnie Stubblefield told me, too.

AJ: Ronnie Stubblefield. He was a good friend of mine.

JT: Did you guys go do that together? I have a sense that maybe you did.

AJ: Yes ma’am.

What Ronnie nonchalantly labels “part of growing up” underrates the fact that this generation of teenage girls and boys comprised an intrepid set of explorers, pushing the geographical and social bounds of travel by automobiles in the name of love. Changes outside of Gloucester made the pursuit of happiness easier: World War II brought travelers to and from the Naval Weapons Station; bridges replaced ferries; cars replaced boats as the primary mode of transportation; and cars themselves became readily available through multiple dealerships at Gloucester Courthouse. As cars became more reliable and accessible, those crazy kids of the post-war era constructed the outlines of youth culture, all about sports and fast food and consumerism.

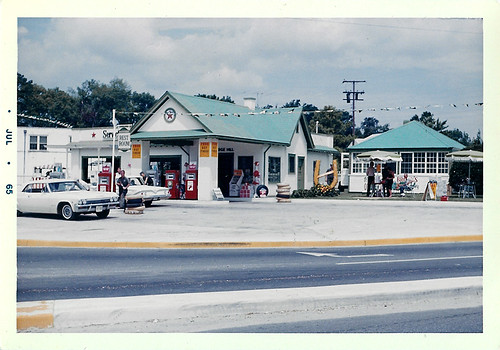

A 1965 photograph of the Edge Hill Service Station in Gloucester Courthouse highlights the expanding car culture and exemplifies the interplay between automobile technology and social scenes.

A 1965 photograph of the Edge Hill Service Station in Gloucester Courthouse highlights the expanding car culture and exemplifies the interplay between automobile technology and social scenes.

We associate youthful rebellion with the flappers of the 1920s; Gloucester, an agricultural community low on leisure time and population density, appears to have missed that boat. Our only two interviewees born in the 1910s, Leola Hogge and J. Ellis Hall, found their significant others at Botetourt School, rarely venturing out of the county for business or pleasure. They met non-native friends on their own turf, at the Botetourt Hotel or the general stores where salesmen and deliverymen stayed. What did they do for fun? The same thing adults did, with adults. Betty Jean Deal recalls that the lives led by the grown-ups in her life were pragmatic and routine:

BJD: My grandparents didn’t get much farther than the neighborhood, the country store, to buy everything they needed. Unless they came to Gloucester to pay their, they called it the hay tax, you know they would come up here for things they needed, too. Everything was in this little court green there: the clerk, the treasurer, the commissioner of revenue. The county was run from that little court circle in the middle of the street.

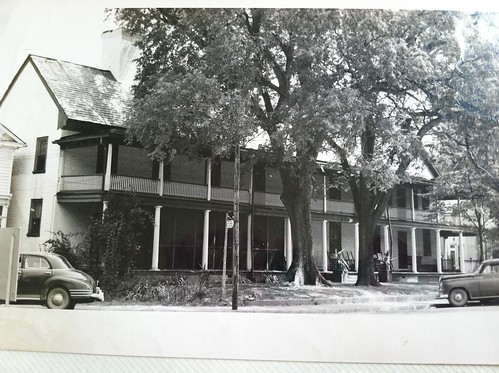

The Botetourt Hotel in the 1930s was a major landmark in the Gloucester social scene.

The Botetourt Hotel in the 1930s was a major landmark in the Gloucester social scene.

Hugh Dischinger made the most of being dragged to court day as a child in the 1920s:

HD: One day- -when somebody ordered something out of the ordinary, they would have it sent to Corr’s store, and then they’d go there and pick it up. And somebody ordered an upright piano. And this piano came in there and it was in a box, a box about that wide and about this tall and it was- it was straight up for about three feet and then it had a slope up to the top. The top was about this wide, see? So Woody and I said, “Man. We’re going to use this thing for court day.” So, we did. We took that slab off of the slanted part up here and that made a perfect counter and we sold stuff out of- [laughs] out of that box. We had stuff in there we would sell- sandwiches and stuff like that for on court days. We set it up outside the store.

Before the school infrastructure that comes with football teams, proms, and homecoming parades, teens relied on the older model of partying at home under adult supervision, or at the movies, or the skating rink at Edge Hill. Friends’ homes and local businesses were within walking distance, and without access to automobiles, how much trouble could a teenage boy get into? “The boys would go out and scratch on people’s windowsill[s] and run,” says Hayes Williams.

In Gloucester, Main Street residents like Dischinger, the sons and daughters of business owners and government workers, led the way towards creating a social scene of their own. The shift towards independent youth culture started with the generation before Ronnie’s, with Gloucester natives born in the 1920s and coursing through teenage angst during the Depression and World War II. Cary Franklin, born in 1923, a member of the USO during World War II and the daughter of Gloucester’s first Ford dealer, represents the tie between travel and leisure time perfectly. Via her father’s car, on trains, or on USO buses, she danced with enlisted men, went clothes shopping in Richmond, and had her picture taken for magazines.

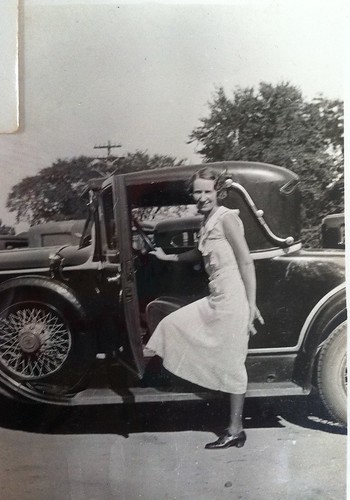

A relative of Cary Franklin’s poses with her father’s Ford near the Botetourt Hotel.

A relative of Cary Franklin’s poses with her father’s Ford near the Botetourt Hotel.

She describes World War II in terms of dating life:

CF: All of the communities would have the boys over for dances and girls would get on a school bus-like thing and go across the river to the dance. I remember one time we went somewhere in Mathews. Then actually, when I was away, the girls were going to the dances in Williamsburg. Whatever club was sponsoring the dance would go to the different communities to pick up the girls to go dance. It was fun meeting all the people. I think the community got involved more then, than they have recently. That they were glad for the boys to come have a day off or a night off and entertain them. You’d meet somebody, and have them over to a meal, anything that would make them glad that they were in the service.

JT: I’m imagining that that would change the social environment considerably, because you have all these people that you’ve never met before.

CF: That’s true.

JT: An influx of men.

CF: That’s right. [JT laughs]

JT: Did that change dating for other women?

CF: Well, a lot of the women—I was thinking about way back to talking about the skating rink—some of the boys that were in the service- men that were in the service- would come to the skating rink unmarried. Later, these girls that they’d met at the skating rink or these dances, particularly if the man was stationed close by, they would be married. There were quite a few that did marry. Their children were in school with my children.

Suddenly, Gloucester women like Cary Franklin were fishing in a much larger pond. No longer confined to their parents’ homes or to Gloucester men, they had opportunities to flirt and dance virtually anonymously in new and exciting environments. This almost urban experience, undergirded with a wartime nationalist message, increasingly contrasted with life at home. There, even as court days died out, old traditions and local living remained strong:

CF: I can’t remember what it was, what it was for, but we had the one big parade that year. We all dressed in colonial costumes. I think I just can’t think of anything really, you know, that we celebrated other than that. Of course, we had the ball games at school, but they were mostly basketball. It wasn’t large enough. The boys wanted to have a football team, but there weren’t that many [JT laughs] and no coach, of course.

Not for long. With the exception of the ever-present requirement of parental consent (what Ronnie Stubblefield calls, “an eyeball approval”), World War II boosted the local and national economy, making multiple family cars and road trips affordable. Plus, the newly-consolidated Gloucester High School built its football team about the same time that the Coleman Bridge was built. For Gloucester teenagers, the grand pinnacle of modernity, postwar optimism, and the sprinting pace of cutting-edge technologies and nationwide industrial growth was the Tastee Freez.

Andy James Jr. explained the life-transforming experience offered by Tastee Freez like this:

AJ: …It was a Tastee-Freez up in Ark, and a lot of the folks from this end of the county, the young people, would gather there on Saturday nights. Down at the south end of the county, I think that’s where I met Roberta, who was at the Tastee-Freez down at the end of the county. Well, she’s right. You’d go down there, and if you had a date, that was fine. You’d pull up in there and get a cheeseburger and a drink or something or another. If you didn’t have a date, then you’d probably just go round and round and round and round [AJ laughs] until you saw somebody that you liked and you’d pull in and you’d talk to them or whatever. Or, you’d have somebody that you wanted to talk to and she knew you wanted to talk to her and she’d conveniently be there. You know.

AJ: …If we went to Mathews, it would be two or three guys a lot of times. During the course of the evening, you would find a carload of girls that didn’t happen to have dates that night. You would pull up beside them at the Tastee Freez and roll the window down and say, “You good-looking thing, you’re sure lucky to see me tonight.” You know, or something like that. [AJ laughs] The word kind of spread around who the- who the cool guys in Gloucester were and who the cool girls in Mathews were. During the course of ball games and all that kind of stuff, you’d kind of- you know, you’d kind of sort of meet them.

It’s easy to imagine Andy James Jr. and his cohorts cruising around a Tastee Freez like this one on a Saturday night!

It’s easy to imagine Andy James Jr. and his cohorts cruising around a Tastee Freez like this one on a Saturday night!

With multiple Tastee Freez franchises in play, the uniformity of the drive-in at either end of either county made visits routine and comfortable from one Tastee Freez to another. The nonverbal signals were expected, and lubricated the relationships between teenagers that had never met before: the rolling down of the window to initiate a conversation, the arrival of “a carload of girls” to denote availability, the circling of the drive-in to denote as much availability as a school of sharks. No doubt the respective roles that boys and girls played also increased a sense of gendered camaraderie: dating was a team effort where everyone learned behavior and boundaries together and no one was left behind.

Don’t miss Andy’s sports reference. Football and basketball games blew cheerleaders and football players into surrounding counties and regions of Virginia and into the lives of one another with some regularity over the course of a high school sports career. Andy’s wife Roberta, a high-school cheerleader, commented on using the bridge to Yorktown and Williamsburg off-season. (And Andy interjects.)

RJ: My group of girls used to trawl to Williamsburg.

JT: Really? Really? Why did you go to Williamsburg?

RJ: Because there were some hot guys-

AJ: More money over there.

RJ: -hot guys over there at the time. [RJ laughs] …We met some of the girls through cheerleading- I did- and we would go up and see them. They’d introduce you to the guys, and when I wanted to tick [Andy] off I’d go to Williamsburg. [JT and RJ laugh]

JT: Where did you go in Williamsburg that was fun?

RJ: We’d go to the Tastee Freez. I remember one night, I had a date with somebody and I wasn’t real happy with that date. I knew he was going to be there, so I played sick and went home early on that date. Then I got in the car with a couple of my girlfriends [RJ laughs] and went up and met [Andy]. [JT laughs]

Roberta brings new meaning to the phrase, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” Like during World War II, the determination to find someone special brought Gloucester kids to the ends of the earth, and back home again. Gloucester teenagers in the fifties performed the dance of courtship across huge swaths of terrain, on both sides of the York River, at every high school football field, and at over four Tastee Freez locations that I have been able to rediscover. They ushered in a modern age of consuming products as a means to a social end, and of using cars and income for leisure. In so doing, they enthusiastically ushered in a youth culture that still finds comfort in the crowd—while preparing young adults for lives led in a context much larger than home.