“… whereas many evil disposed persons Inhabitants of this Colony

contrary to their duty and Allegiance on the first day of May in the

34th [year] of the King’s Reign and since tumultuously and

Mutinously assembled and gathered together Combining and

presuming to reform this Government by cutting up Tobacco plants

and to perpetrate the same in a traiterous and rebellious Manner

with force and Arms entred many plantations resolving by open

force a General and Total destructions of all Tobacco plants to the

hazarding the Subversion of the whole Government and the Ruin and

destruction of his Majesty’s good Subjects if they had not been timely

suppressed for which Treasons and Rebellions against his Majesty

and this Government some Notorious Actors had been Indicted

Convicted and Condemned and Suffered such pain and punishment

they deserved for their Treason and Rebellion and for as much as

many people had been seduced from their Allegiance by the Specious

tho’ false pretences of the designers and Contrivers of those Crimes

Misdeeds Treasons and Rebellions…[sic]”

-Proclamation of Lord Thomas Culpeper, May 22nd, 1682

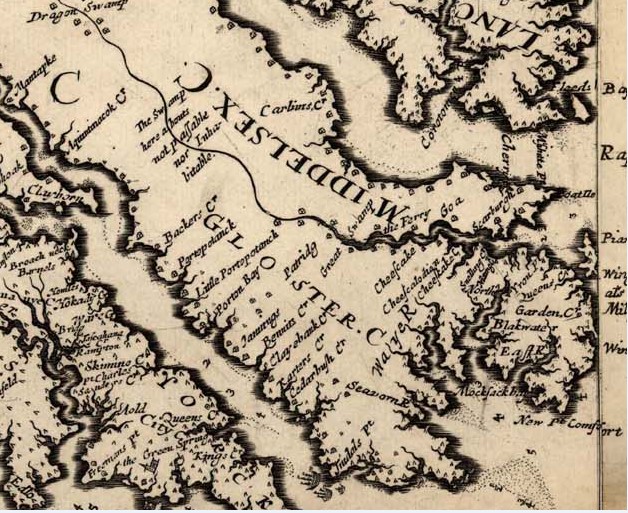

During the first weeks of May of 1682, disgruntled planters began destroying their

own, and then their neighbors’, tobacco plants in Gloucester County and neighboring New

Kent County. While on its face this seems ludicrous, it was an effort to raise the price of the cash crop and ultimately affected at least four counties (Gloucester, New Kent, Middlesex, and “Old Rappahannock,” or present-day Essex and Richmond Counties). The so-called Plant-Cutter Riots saw over half of the in-ground tobacco destroyed in Gloucester County alone1, where the uprising allegedly began. So grievous were the actions of the nearly 20 ‘plant-cutters’ that were eventually identified and tried in court that two were executed by hanging, an example to future would-be rebels. My name is Brian Riley and my recent fellowship with the Fairfield Foundation allowed me to fully research this little-known aspect of 17th-century Virginia history and pursue a theory that there is some connection between this event and Fairfield Plantation.

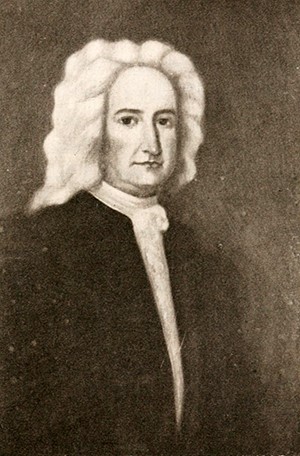

Surviving colonial records are lamentably mute on the involvement of Lewis Burwell II, Fairfield’s owner in 1682. Gloucester County records that may have contained such information were likely destroyed in major fires that destroyed the clerk’s office (1820) or the records in general (1865). But we find his stepfather, Philip Ludwell I, at the center of the colonial government’s response to the Plant-Cutter Riots. Sitting on the Council in 1682, Ludwell’s role in the colony’s response to the ‘plant-cutters’ is the strongest connection between Fairfield and these events.

After marrying Lewis Burwell II’s mother, Lucy Higginson in 1667, Ludwell resided at Fairfield until her death in 1675. In lieu of the fact that his two children by Lucy Higginson Burwell Bernard Ludwell, Joanna and Philip II, were born at Fairfield (usually referred to as ‘Carter’s Creek’) it seems that Ludwell treated Fairfield as a homestead rather than just another plantation to maintain and operate. Ludwell also likely played an important role in Lewis Burwell II’s upbringing as he was just a few years older than his new stepson (Lucy was quite a bit older than her new husband). A powerful and loyal councilor, Ludwell had been instrumental in the colony’s response to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Despite the paucity of colonial records, two sources, the Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia and the Calendar of State Papers prove invaluable to the study of the events of 1682 and Ludwell’s role in them. In the Executive Journals we find a record of Ludwell’s attendance (he never missed a meeting of the Council the entire year) and the progression of the colonial government’s handling of the Plant-Cutter Riots. The Calendar of State Papers offers supplemental documents relating to the proclamations of the Council as well as from King Charles II himself. Together, these two sources lend more than ample evidence of Ludwell’s role in the colonial government’s swift response to the events of 1682.

Though present for every meeting of the Council after May 3rd, Philip Ludwell is not mentioned in direct connection with the suppression of the Plant-Cutter Riots until September 30, 1682. At that meeting, Ludwell is included among fellow councilors Nathaniel Bacon (the elder) (Lewis Burwell II’s extremely wealthy uncle-in-law), William Cole, and John Page concerning the arrest warrants for ‘plant-cutters’ Somerset Davis, Zuperan Burwell (no known relation), Robert Alcock, John Oakes, and John Cockin. Upon their capture and delivery to the “Sherrife of York County”, these four councilors are noted as being “hereby impowered & desired to doe and Act therein, as they think necessary [sic]” after being ‘acquainted’ of their incarceration. In this example we see Ludwell transcend his perfunctory role as mere member of the Council to an agent in the suppression and prosecution of the ‘plant-cutters’.

On January 11, 1683 we find Ludwell again in the Executive Journals with a role beyond being merely counted present at the Council. In this meeting Lord Thomas Culpeper asks the councilors for “an account of ye Government, since my departure out it in August 1680, particularly as to ye…calling ye Assembly last Aprill and ye occasions rise, growth and Progresse of ye late Insurrections and Commotions about Tobacco

Plants destroying, with all other matters relating to ye same [sic].” Lord Culpeper prefaces the request that King Charles II expects the report “with all speed…” Found in the Calendar of State Papers, and delivered on May 4, 1683 to the Lords of Trade and Plantations, the report from the Council conveys much of what was already known about the Plant-Cutter Riots (the debate over cessation, the affected counties, their duration), but offers important insights into the sentiments of the councilors, and thus possibly Ludwell himself.

After summarizing the events up to the meeting on April 26th, the Council reports,

“…We knew of several men who were very active in the work [plant-cutting], but as they were inconsiderable people we forbore to prosecute, in the hope of discovering in time not only the actors but the authors. The inhabitants of the country are mostly extremely poor; their only commodity, tobacco, having of late years yielded them little, while their poverty inclines them to listen to all suggestions, however foolish, which are insinuated into them by subtle factious persons, who mask their private ends under the show of public utility…”

Apart from suggesting a conspiracy, this portion of the report certainly underscores the elitist demeanor held by the Council towards the seemingly ignorant and impressionable ‘common’ planters. This sentiment could have carried over from Bacon’s Rebellion, as out of the nine councilors who penned the 1683 report, five of them, including Ludwell, were named as “Trayters” in Nathaniel Bacon’s “Declaration in the Name of the People” on July 30, 1676. However, despite these sentiments towards the ‘common’ planters beneath them, the Council report nevertheless ends with a call for a ‘limitation’ on the planting of tobacco to “advance the present low state of the inhabitants of Virginia.” Their response is clearly elitist, but also pragmatic, as it may have served to downplay the severity of the riots to reduce the larger risk of continued of continued unrest.

While it appears that perhaps some members of the Council were sympathetic to the plight of the ‘common’ planters (hence the meeting on April 26th to try and address the tobacco crisis), it may be reasonably presumed that Ludwell was one who was not. The language of the Council’s report in 1683 echoes language found in a letter from Ludwell to Secretary Sir Joseph Williams in 1676. In discussing the adherents of Nathaniel Bacon, Ludwell insists that Bacon “gathered about him a rabble of the basest sort.” Furthermore, Ludwell’s role in the suppression and prosecution of the participants of Bacon’s Rebellion, his marriage to William Berkeley’s widow (he and Ludwell were also cousins), and his leasing of his Green Spring plantation to both Lord Culpeper and then to Lord Effingham showcase his intimate connection to the highest powers in the colony, and thus lends credence to his probable disdain for the ‘common’ planters and for those especially who participated in the Plant-Cutter Riots. Lamentably, however, the surviving colonial record offers no document where one can glean the personal sentiments of Ludwell towards the ‘plant-cutters.’

Despite the fact that no colonial records detail the on-goings at Fairfield Plantation during the year 1682 (aside from the birth of Lewis Burwell II’s son on October 9), or even the reaction of Lewis Burwell II to the events of 1682, the documents that do exist tell the story of one of Fairfield’s most powerful occupants and his handling within the Council of the Plant-Cutter Riots. That Philip Ludwell I was instrumental in

the response, prosecution, and documentation of the Plant-Cutter Riots lends a direct connection between the riots and Fairfield Plantation. And, though few colonial records exist from Gloucester County from the late 17th century, the work of the researcher is never finished, as overlooked or misplaced documents may yet survive in dark corners of the archives waiting for a diligent researcher to peer inside.

As well as being an independent researcher, Brian Ellis Riley teaches college and high

school History and Government in the Richmond area. The Fairfield Foundation’s Cecil

Wray Page Jr. Fellowship in Plantation Studies offered a unique opportunity to research

a relatively under-researched period of Virginia’s colonial past, as well as to engage

overlooked archival records. Mr. Riley’s research into the Plant-Cutter Riots will continue

beyond the fellowship, investigating the connections and correlations between Bacon’s

Rebellion in 1676 and the events of 1682.

1 “Sir Henry Chicheley to Sir Leoline Jenkins,” in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West

Indies: Volume II, 1681-1685, ed. J.W. Fortescue (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1898), 226-242. This correspondence is dated May 30, 1682.

Suggested Readings:

-Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia Vol. 1 (June 11, 1680-June 22,

1699)

-Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 11, 1681-1685

-Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1659/60-1693

A great article about the plant-cutters incident. More research like this is needed to fully understand the roots of current day Gloucester and surrounding counties. Thanks for the research.

Thanks so much for a wonderful, enlightening article and for all of the research that went into it. Keep up the great work!

I really enjoyed learning about this period in our history. It has inspired me to follow up studies on my family members who were early Virginia settlers. Thank you. Donna Matzeder