Written by Sara Lewis, Development Officer

As we celebrate with fireworks and watermelon and reflect on nearly 250 years of American independence, we are reminded of the Burwell family of Fairfield and their involvement in the Revolutionary War. Their lives exhibit the ideals and contradictions inherent in the American experience.

On an ordinary 4th of July in 1764, twelve years before the Declaration of Independence was written, a newborn Lewis Burwell (1764-1833), is believed to have been baptized.[i] He was the last Burwell to own Fairfield (also known at the time as Carter’s Creek), and the son of Lewis Burwell (1737-1779) and Judith Page (1745-1777), He was one of four children, preceding Nathaniel Burwell (d.1781), Alice Grymes Burwell (1763-1820), and Mann Page Burwell (b. 1768). He followed a long line of Lewis Burwells (and one Nathaniel), who owned Fairfield since 1648. He and his siblings witnessed the American Revolution through the eyes and actions of their parents, and through events that happened within a day’s journey of their house. They must have also pondered their position in society, as did the hundreds of people of African descent whom their family enslaved.

The last Lewis Burwell of Gloucester was born to a position of social and political privilege as the grandson of another Lewis Burwell who had been a member of the Governor’s Council and Acting Governor of Virginia. His father was a Justice of the Peace, Sheriff, and member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. When this last Lewis Burwell was six years old, his father paid tax on a 7,000-acre estate with 138 tithables, most of whom were enslaved men, woman and children. His uncle, John Page of Rosewell, was a friend of Thomas Jefferson, who visited frequently, especially in his youth to woo young Lewis’s aunt Rebecca Burwell. Rebecca spurned Jefferson for Jacquelin Ambler, and they were married about a month before young Lewis was born.

When the last Lewis Burwell was 10 years old, his father signed the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions, “An Association, Signed By 89 Members of the Late House of Burgesses.” Then he signed the Non-Importation Act of 1774. In 1775, he was elected to represent Gloucester at the Virginia Convention in Williamsburg and later Conventions in Richmond. He was probably present when Patrick Henry delivered his fiery “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death!” speech in St. John’s Church to the delegates of the Second Virginia Convention. He likely voted for Independence on May 15, 1776, for the Virginia Declaration of Rights on June 12, and for adoption of the first written Constitution of Virginia on June 29. His uncle John Page, then Acting Governor, accepted the Declaration of Independence for Virginia.

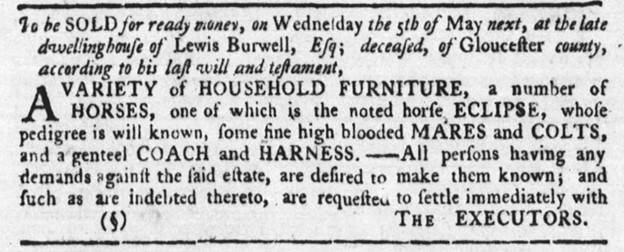

The last Lewis Burwell was only 13 years old when his mother died in 1777, and 14 when his father joined the Nelson brothers of Yorktown to form a corps of Light Dragoons. But his father’s name was crossed off the list of Dragoons to serve in Baltimore in 1778 and his death was announced in the Virginia Gazette in March 1779. Young Lewis and his siblings were sent next door to live with their uncle John Page and his wife Frances Burwell, their first cousin once removed, at Rosewell. The next month, when Lewis was 15, executors including his uncle listed his estate for sale, including his father’s prized racehorses.

Virginia Gazette, 9 April 1779

The “late dwelling house” did not sell, probably because the manor was over 75 years old, and many potential buyers sought land west of the old Tidewater region. In addition, Lord Cornwallis’s Southern Strategy had begun in 1778, shifting the focus in a war that up to that point had been fought primarily in the northern colonies. The Southern colonies paid more attention as Cornwallis moved from Georgia toward the Carolinas. Once the British moved to Yorktown, enslaved people escaped to join them, toward what they hoped would be freedom. When the British surrendered and left, the formerly enslaved people scattered to avoid recapture. A runaway slave advertisement mentioned that the deceased Lewis Burwell’s plantation, was a place where runaways were known to be harboring after the Siege of Yorktown.[ii]

In 1782, when the last Lewis Burwell was 18, his estate was taxed on 6,800 acres in Abingdon Parish, 140 Negroes, 14 Horses, and 205 Cattle. In Petsworth Parish, he owed taxes on an additional 1,000 acres, 28 Negroes, 2 Horses, and 54 Cattle for his plantation known as Purton. As the last Lewis Burwell came of age, he felt the weight of his inherited debt, a debt his father said he was “desirous of paying every shilling that I am indebted” in a 1773 Virginia Gazette advertisement for the property. Young Lewis Burwell may have known about his father’s struggle to pay down his debt by selling property and slaves. The advertisement spelled out his father’s anguish and asked his creditors for understanding of the losses he would sustain due to his indebtedness and its impact particularly on his “several children, whose dependence is entirely on what may hereafter be raised from my estate.”

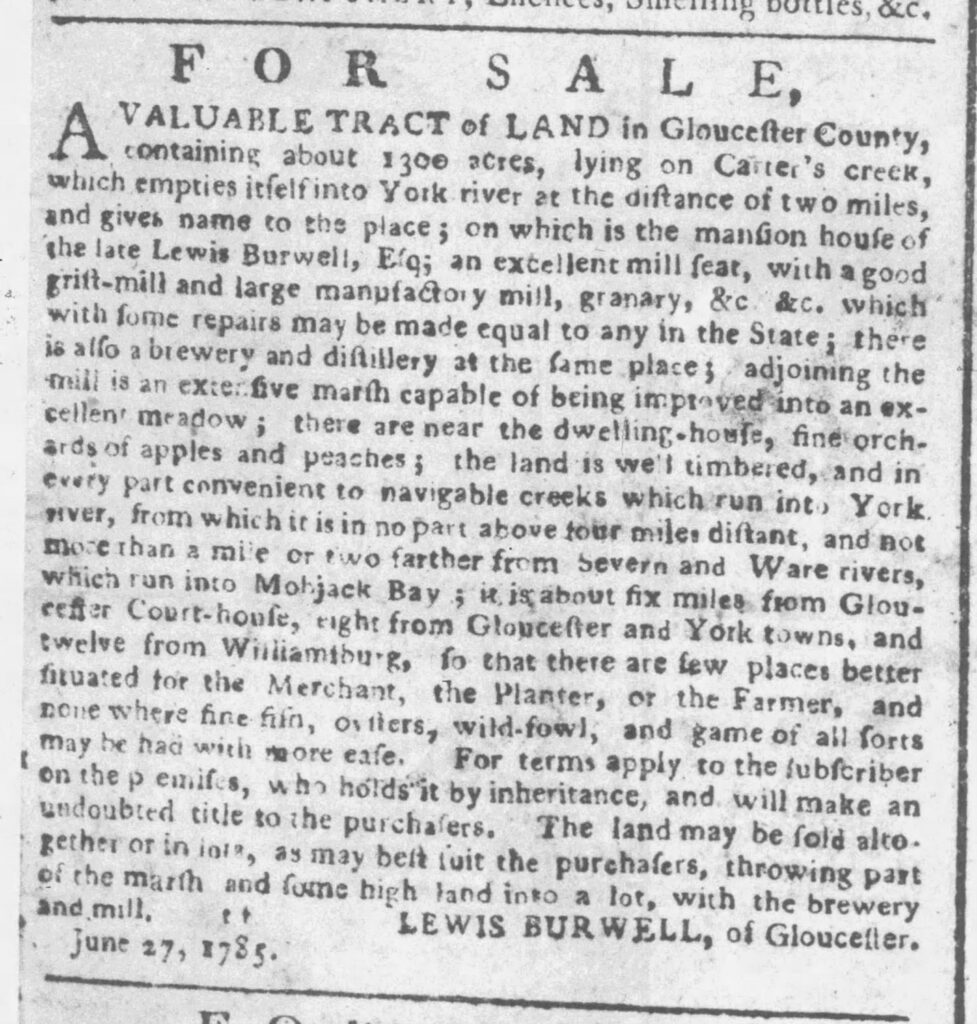

In 1785, when Lewis Burwell reached the age of majority, he advertised Carter’s Creek for sale once again. It appeared in the Virginia Gazette five days after his 21st birthday.

Virginia Gazette, 9 July 1785

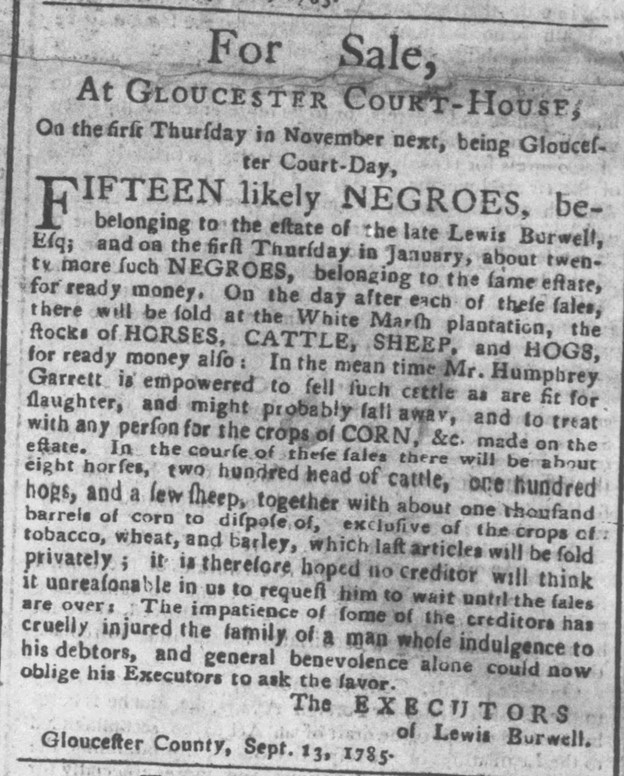

It did not sell by the fall of that year and the executors found it necessary to raise funds by selling enslaved people, horses, cattle, sheep, hogs, corn, tobacco, wheat, and barley on the Gloucester Courthouse steps and at the estate. The executors pleaded for understanding: “The impatience of some of the creditors has cruelly injured the family of a man whose indulgence to his debtors, and general benevolence alone could now oblige his Executors to ask the favor.”

Virginia Gazette, 1 October 1785

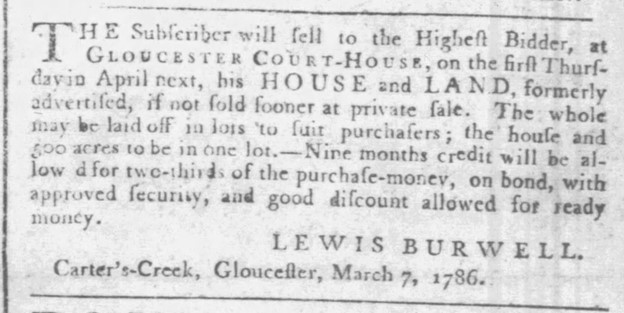

By the spring of 1786, more drastic matters were necessary. The estate would be broken up as required and sold to the highest bidder, with the 500 acres surrounding the manor sold in one piece.

Virginia Gazette, 22 March1786

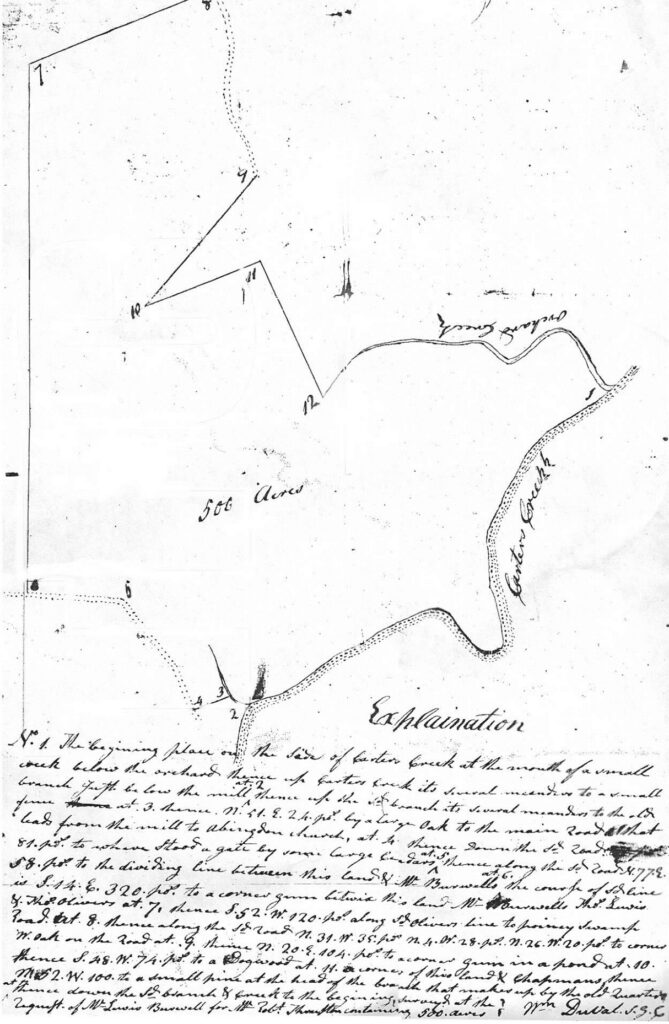

At last, Lewis Burwell of Fairfield/Carter’s Creek sold 500 acres and the manor to Mr. Robert Thruston in 1787.

1787 survey requested by Mr. Lewis Burwell for Mr. Robert Thruston,

Robert Reade Thruston Collection, The Filson Historical Society

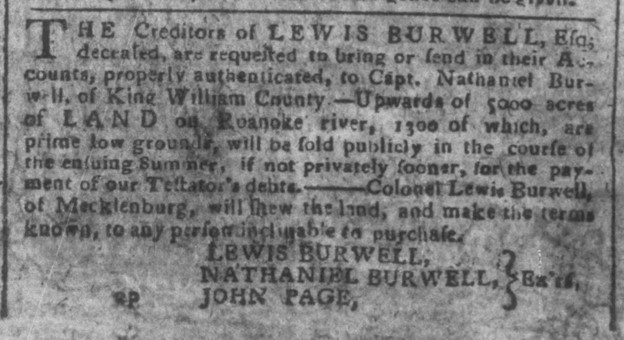

As with many Virginia colonial estates, the plight of the Burwells at Fairfield, and the Pages at neighboring Rosewell, reflected gentry ambitions that were unsustainable. Many members of the extended Burwell family were moving to central Virginia around the time of the American Revolution to plant fresh land with tobacco. The old Tidewater plantations had shifted largely to food crops, cattle and timber, including barrel staves for export. Lewis Burwell’s father may have considered a move west, as suggested by the advertisement of his land on the Roanoke River for sale. A cousin, Col. Lewis Burwell, who had moved with his family to Mecklenburg County from Kingsmill in James City County, would show the property to those interested in purchasing it.

Virginia Gazette, 9 April 1785

The American Revolution brought devastation of property, labor force diminishment, and cessation of British credit. Like the other colonies participating in the Revolution, Virginia’s trade with Britain and the West Indies, partners in the triangular trade system, was disrupted. The lack of cash, credit and markets resulted in a depression that historians have noted as being as crushing as the Great Depression would be 250 years later. The financial panic of 1791 led to the first financial bailout in American history, orchestrated by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. It appears that the realities of fiscal responsibility and familial welfare very quickly supplanted any inclinations the Burwells may have had to extending the ideals of the American Revolution and the new U.S. Constitution to the people they enslaved. One of the major consequences of the revolution and ensuing financial woes was the division of many large plantations into smaller farms, and the sale of many enslaved persons to settle debts, often splitting families and sending them to unfamiliar places further south and west.

Despite the disruptions of the time, Lewis and his siblings landed on their feet.

- Nathaniel, married twice and continued to live in Gloucester, where he served as Sheriff. His daughter, Claudia, married the son of Chief Justice John Marshall, who was also her cousin. Claudia’s Great Aunt Rebecca Burwell Ambler’s daughter had married the Chief Justice.

- Alice Grymes Burwell married William Clayton Williams, who became a successful attorney practicing in Richmond, Virginia.

- The youngest son, Mann Page Burwell, continued to live in Gloucester. Upon his death he freed his slave Peter Burwell, but laws dictated that Peter could no longer live in Virginia, which Peter believed was worse than slavery because he could no longer see his family[iii].

It appears that Lewis lived in Gloucester until he sold the core plantation property to Robert Thruston. On May 29, 1789, he married his second cousin, Judith Kennon, at St. John’s Church in Richmond, where his father had spent long days serving in the Virginia Convention. They had seven boys and four girls, who grew up in Richmond. Lewis died in 1833 at the age of 69, but it is unclear where he was interred. Richmond Hustings Court records for 1834 show payment for a coffin and case, hearse, and sexton.[iv] Judith continued to live in Richmond’s Monroe Ward and died at the age of 77 in 1849. She and several of the children are buried in Shockoe Hill Cemetery.

Burwell plot at Shockoe Hill Cemetery. A scroll chiseled into a side of the obelisk in the center of the plot includes the name “Lewis Burwell,” which probably indicates it was placed in memory of their son, yet another Lewis Burwell, who was buried there in 1840.

The first anniversary of American Independence to be celebrated in Gloucester occurred on July 6, 1858.[v] On that day, troops remembering the American Revolution and the War of 1812 gathered at Hickory Fork and paraded to Carter’s Creek, then the home of John Leavitt. There was a sumptuous banquet with many toasts offered, and a ball concluded the day’s events in the home where the last Lewis Burwell of Fairfield was born 94 years earlier.

[i] Unreferenced sources note his baptism on July 4, 1764.

[ii] Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser (Hayes), January 15, 1785.

[iii] Legislative Petitions, Gloucester County, 1812-12-12, Library of Virginia.

[iv] Hustings, Book 5-6, 1828-1831, Library of Virginia.

[v] Richmond Enquirer, Tuesday, July 27, 1858.

Wow! This made my day!

When you mentioned those who moved west in the 1760s & later, my ancestress Mary Burwell and husband Lewis Hale wound up in Elk Creek, VA & he is a DAR patriot! Mary was the daughter of Lewis Burwell I/II and Mary Willis—a sister to Rebecca Burwell!

This is exciting to see!

Glad you enjoyed reading it, Ann, and that it made a connection to your ancestors.

Thanks,

Sara

Well written and researched, not to.mention fascinating. Good job Sara

Thank you, Breck!

Excellent, well documented article. It makes absolute sense that the States post revolution would have an economic depression. I was not aware of the depth and severity of it until now. It reminded me of the economic consequences to Mathews and Gloucester during and after the Civil War. In many ways, Mathews County did not fully recover economically until after WW II. The automobile, cheap gas and military installations and the shipyard enabled men to live in Mathews and not have to go to sea to make a living.

Thanks, Danette. Yes, the recovery period for areas impacted by war in any age and anywhere is long and long remembered by those who endure it.

Sara

Well researched and well narrated history. Parallels what was happening to my more immediate Randolph ancestors.

Thanks, Prinny.

Sara