We love doing archaeology at a variety of sites across the Middle Peninsula, but Fairfield Plantation will always be our home. There are thousands of fascinating artifacts that have been recovered from the manor house and surrounding property, and we don’t always have the time or resources to give them the attention and care they deserve. One exciting find, however, is currently being preserved.

During excavations inside the Fairfield manor house in 2001, we recovered a fragmented cast-iron stove. The majority of the pieces were clustered beneath the first-floor hearth, where the stove likely sat. Over sixty pieces of the stove were recovered, including several large fragments. Some pieces were clearly identifiable, such as a lid, door, and – interestingly – five legs. One of the legs is stamped with the date 1883; another piece, although degraded, reads “Excelsior Stove Works”, and the stove door reads “Patrol”.

Former intern Colin uncovers portions of the stove in the manor house ruins in 2002

Fragments of the cast iron stove before conservation

Cast iron stove leg dated 1883

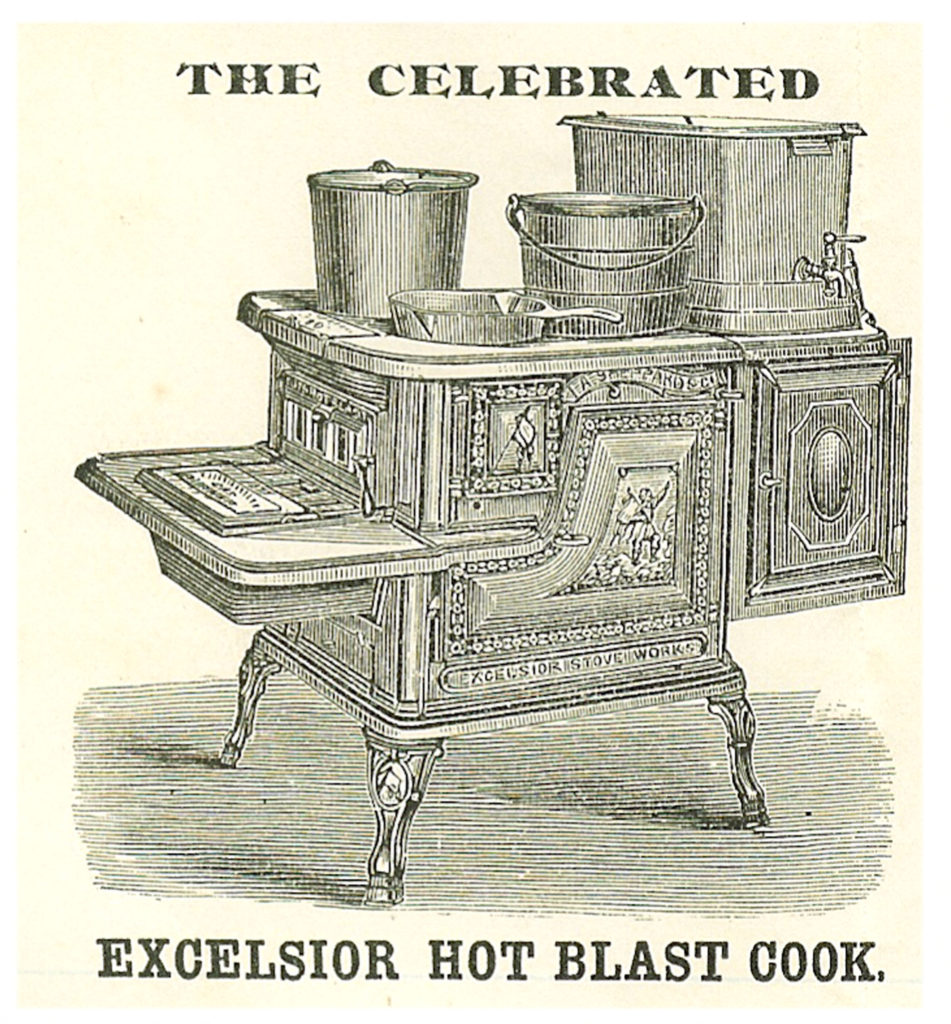

While we have not found pictures of a Patrol-model stove, we do have an advertisement from Marchant, Trader, & Co., in Mathews County with an image of an Excelsior Stove Works “Hot-Blast” cook stove. Although the stove in that image has only four legs, the side panels are nearly identical to the pieces recovered from Fairfield.

An Excelsior cook stove advertisement from Marchant, Trader, & Co. in Mathews

Fairfield Plantation is about more than just the original occupants, the Burwell family. This Excelsior stove would have been owned by the last known resident of Fairfield, an African-American woman whose name is currently unknown. We can learn about her through artifacts like the stove, which were in the house at the time of the fire that destroyed it in 1897. We also have a description of Fairfield recorded just days before the fire, which describes a woman feeding corn cobs into a stove. While we cannot know for sure that this is the stove described, it is enticing to think of it as such.

Victoria holds the stove door fragment which reads “Patrol”

After the stove’s excavation, it went into storage. A few pieces were conserved, but the majority sat in our lab for over fifteen years. The iron grew increasingly rusty and fragile, with pieces starting to crumble, and we wanted to stop its deterioration. We applied for a grant through the Virginia Association of Museum’s Top 10 Endangered Artifacts program to fund conservation of the stove. Although we did not receive funding through that program, it led us to Kate Ridgway at the Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Kate generously offered to take on the conservation project pro bono, and we accepted.

We dropped the stove off at the DHR in late January 2018. Because Kate is volunteering to take on this project, there is no time table or rush (on our part or hers) to complete it. It will most likely take years before the stove is conserved. We signed off on the treatment proposal in early March, and the long, slow process of conservation began.

The cast iron stove fragments are currently in the hands of DHR’s conservator Kate Ridgway

The first steps in Kate’s treatment proposal are to document the artifacts’ current condition with photographs and x-rays. This helps the conservators assess how stable the iron currently is and what treatment is appropriate. Then they will begin to remove the rust where possible using air abraders and repeated alkaline baths. Once this is complete, a surface treatment will be applied to make the items stable for storage or display. All of this sounds simple, but each step takes time and a high degree of attention and care.

We will continue to check in with Kate to see how the stove’s conservation progresses. Look out for more blog posts on this fascinating subject in the future!

Very interesting article.

Gloria