Disclaimer: Some images contain mature content.

Every spring over 20,000 runners gather at the east end of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia to participate in the Ukrop’s Monument Avenue 10k. Spectators line the wide grassy medians to cheer on the runners while enjoying live music and beautiful scenery. The course spans the length of Monument Avenue, running through 6.2 miles of elegant mansions, historic churches, and the towering monuments for which the road is named. It’s a lively celebration that draws tens of thousands of visitors to the city every year, and it takes place in the shadows of one of the nation’s greatest controversies.

Five out of six of the statues that characterize Monument Avenue depict Confederate leaders, which has become an increasingly heated topic of debate in recent years. Not long after the violent 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Richmond residents began lobbying for the removal of the Confederate statues on Monument Avenue. Mayor Levar Stoney addressed the issue by establishing the Monument Avenue Commission, a group dedicated to formulating a plan for the statues based on public feedback. In 2018 the commission published a report that suggested adding new monuments which represent a more diverse history, and posting new interpretive signs at the existing statues which provide better historical context. These recommendations were formed after extensive public outreach and engagement with the local community.

The following spring, Dr. Bernard Means, professor and director of the Virtual Curation Laboratory at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) reached out to the Fairfield Foundation to ask if we’d like to collaborate on a project to document the monuments in 3D using our drone before the anticipated changes took place. The Virtual Curation Lab has a long history of 3D scanning artifacts from historic sites across the globe, but does not have the resources to scan objects as large as the Monument Avenue statues. We were excited by the opportunity, and Dave and Ashley headed up to meet with Dr. Means on April 29, 2019.

Photo by Fairfield Foundation.

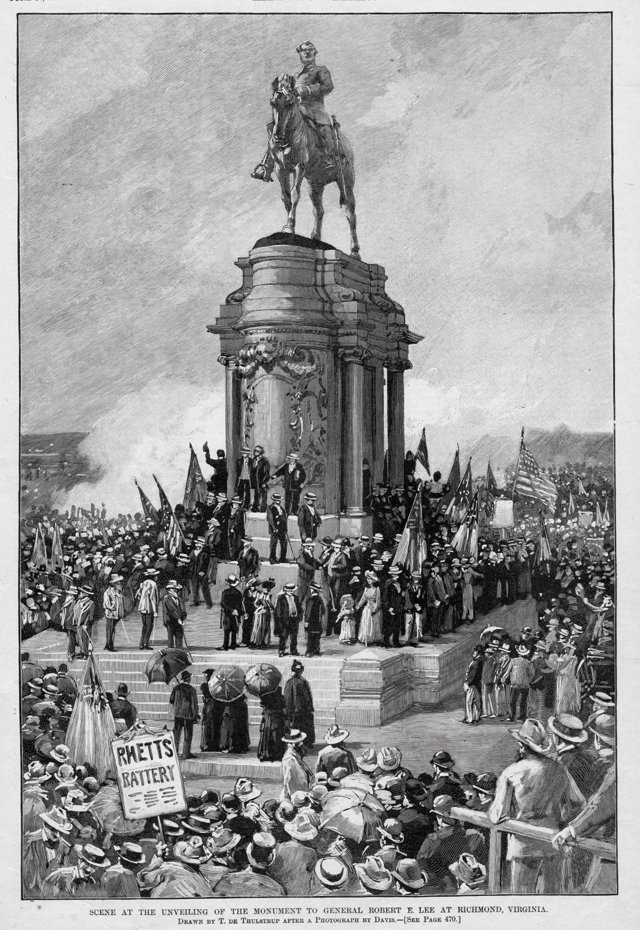

Monument Avenue is listed as a Historic District and a National Historic Landmark on the National Register of Historic Places. Planning for the Avenue began in 1888 when a large statue of Robert E. Lee was proposed in an undeveloped area west of the city. The statue was to be the centerpiece of a new neighborhood that would house the most elite members of Richmond society. The 61-foot tall monument was unveiled two years later, in front of a crowd of 150,000 people, and Monument Avenue was born. Statues of J.E.B. Stuart and Jefferson Davis were added in 1907, then Stonewall Jackson in 1919 and Matthew Fontaine Maury in 1929. The road was paved, trees were planted, and elaborate homes, churches, and apartment buildings sprouted up on both sides of the street. Monument Avenue quickly became one of the most desirable neighborhoods in Virginia, and a favorite destination for locals and tourists to visit.

When we arrived in Richmond that day in April 2019 our goal was to create 3D models of each of the monuments, which would serve as an interactive record of what they looked like prior to any potential changes. Monument Avenue has remained largely unaltered since the 1930s, which is one of the things that makes it unique. One exception was the erection of a sixth monument honoring Arthur Ashe at the west end of the road in 1996. Ashe, a Richmond native, was an African-American tennis champion, Civil Rights activist, and fervent advocate for education. The city erected the statue three years after his death in an attempt to begin diversifying the history represented on Monument Avenue. The decision was heavily protested by pro-Confederate groups.

Photo by Fairfield Foundation.

We began our survey at the east end of the Avenue with J.E.B. Stuart, then made our way west capturing photographs of Lee, Davis, Jackson, Maury, and finally Ashe. We took 100-200 photographs of each monument with the drone, capturing them from every possible angle. Back at the lab, we stitched the photographs together to produce detailed 3D models of each one. We then posted them in a collection on Sketchfab, where they are freely accessible to the public. We also created a storymap tour of the Avenue that features historic information about each monument (see below).

The purpose of these models – in addition to preservation – was to draw attention to the history of the monuments as objects and the role they played in the development of the city. We also wanted to draw attention to the debate over their presence on the Avenue and promote more informed conversations about what they represent and how to better contextualize them. In the months that followed our initial documentation we received a number of requests to download the models for art exhibits, virtual reality projects, and master’s theses. We were happy that the models were helping people illustrate different perspectives on the monuments, and that we could contribute to the conversation through our work. What we didn’t realize was how relevant they would become almost exactly one year later.

On May 30, 2020 several hundred people gathered at VCU and marched down Monument Avenue to protest the killing of George Floyd. During the demonstration, all five Confederate monuments were vandalized. While the monuments have been the target of vandalism before, this time was particularly extensive and included countless messages protesting racism, injustice, and inequality. Demonstrations continued throughout the following week, and each night the monuments accumulated more and more graffiti. In response to the frustration exhibited by protestors and the community, Governor Ralph Northam made an announcement on June 4 that the state will remove the 130-year-old statue of Robert E. Lee as soon as possible. Ashley and Jane returned to Monument Avenue that day to re-document the monument with our drone, recording it in its altered state before it disappears. We also re-documented the Jefferson Davis monument, which protestors tore down just a few days later. Less than a month later, Mayor Levar Stoney approved and initiated the removal of the remaining Confederate statues on the Avenue.

Photo by Ashley McCuistion.

Photo by Fairfield Foundation.

Photo by Fairfield Foundation.

Photo by Ashley McCuistion.

What’s happening in Richmond is not a new scenario. On July 9, 1776 a group of 40 people gathered at Bowling Green in Lower Manhattan and used ropes to tear down a statue of King George III to symbolize their rejection of British tyranny. On November 9, 1989 Germans gathered in mass to tear apart the Berlin Wall, demonstrating their opposition to Communist rule. On April 9, 2015 students in Cape Town, South Africa cheered as a statue of Cecil John Rhodes – a colonizer who set the stage for decades of extreme racial inequality in the country – was taken down after numerous protests. Statues of communist leaders were destroyed across Europe and Africa throughout the 20th century to celebrate liberation and democracy, and monuments to Christopher Columbus have been removed from cities across Latin America to refocus the historic narrative on indigenous populations.

Monuments mean different things to different people. To some, the statues on Monument Avenue symbolize a past they are proud to inherit. To others, they represent centuries of oppression and injustice that continue to influence the treatment of minority communities across the United States. When a monument is removed the goal is not to erase history, but to demonstrate a departure from the political values the monument represents – values that are no longer embraced by the local population. Removal of the statues on Monument Avenue represents an emancipation from the values of the Confederacy, a move that government officials hope will help the state and nation heal and move forward.

Photo by Ashley McCuistion.

Regardless of where you fall on the debate, we cannot deny that these monuments have played a significant role in Richmond’s history. However, we should also recognize that that role doesn’t end when the statues come down. The empty pedestals and graffiti reflect a new moment in history, one that is just as important to document and remember as the last. As runners and spectators gather for the next Monument Avenue 10k the scenery will be different. The shadows cast by the monuments will have changed, as will the conversations they inspire. We’re proud that we were able to 3D model the monuments before the protests, especially knowing that many of them will likely never return to their original state, but we are also proud to have the opportunity to document how they’ve changed. We cannot expect our representations of the past to be static when history is constantly changing, but as archaeologists we can ensure each stage of the evolution is recorded and preserved for future generations.

This is particularally relevant today and well stated. Glad you were ahead of the curve to participate in this. Change is good. Our diverse population is speaking and we need to listen and be more inclusive. Our history and perspectives have been skewed. History needs to be accurate. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for your comments. What is happening today shows that history is still very relevant in our society and we still have much to learn.

Thank goodness you were able to document the statues before anything happened to them. Actually this would be a great (altho incredibly extensive) project for Virginia. So many small towns with commemorative statues that should be recorded in the same manner.

Thank you for making the effort to record these historic times as they actively unfold.

I think what you’re doing is great–I support you.

But–when you make completely incorrect statements, I have to object.

“Five out of six of the statues that characterize Monument Avenue depict Confederate Generals,”

Here “were” the statues on Monument Ave:

Stuart — a Confederate general

Lee–a Confedete General

Davis–a civilian bureaucrat, not a military officer

Jackson–a Confederate general

Maury–a Confederate commander in the navy, not a general

Ashe –a renowned tennis player

is totally incorrect! 3 only were generals–one was a civilian–and one was a commander in the navy.

this upsets me very much for your crdeibility–I’m so sorry to have to say that.

I’ll not believe anything you state from now on.

I admire your site and your work–but these kinds of mistakes make me question your credibility completely.

So sad—I’m so sorry that I have to “unbelieve” all your research now.

Thank you for the comments on our blog. You are correct in pointing out our error concerning the statues, and we will change that. We know who the statues depict and we meant to say ‘Confederate leaders’ rather than identifying them all as generals.

Let me get this right, this is acceptable anarchy?

This is not action against a king, this is America due process is the civil rule. You reap what you sow.