Guest blog written by Colleen Betti, doctoral candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill and long-time Fairfield Foundation friend and collaborator.

In a December 2020 blog, I gave brief updates on my excavations at three of Gloucester’s historic Black schools: Woodville, Glenns/Dragon, and Bethel. Now I’d like to dive deeper into the archaeology of Woodville School and explain why the deposits that have been found at the site are both amazing and mysterious.

The presently standing Woodville Rosenwald school was built in 1923 and was used as a school until 1938. The current school was built on the same lot as an early two-room, two-teacher school. This earlier school was built around 1886 and presumably stood until just before 1923. We have no photographs of the earlier school and still don’t know where on the lot it was located.

Questions about what archaeology could reveal about education, Rosenwald Schools, and how schools changed through time from the 1880s through 1930s led me to start excavations at Woodville in 2019 as part of my dissertation research. In addition to a full shovel test survey across the one-acre lot, 20 test units of varying sizes have been excavated, mostly in the front yard.

My excavations have focused mainly on the standing school’s front yard, but that is not to suggest that other areas of the site have been fruitless. Test Units 3 and 12, excavated near the driveway, produced intriguing finds, including a 14k gold collar pin, slate pencils, a large quantity of writing slate, medicinal bottles, possible desk or stove parts, and buttons. Excavations near the shed (Test Unit 1 and shovel tests), which appears to have been built at the same time as the Rosenwald School and could have functioned as a home or cottage, uncovered an incinerator pile relating to the domestic occupation of the site. The incinerator pile artifacts are important to the history of the site, as they give insight into the lives of an African American family in the mid-20th century. Finally, Test Units 5, 6, and 10 around the school foundations revealed artifacts spanning the site’s entire occupation including ceramics, many beads, 19th-century medicinal bottles, slate and slate pencils, wooden pencils, and hair combs.

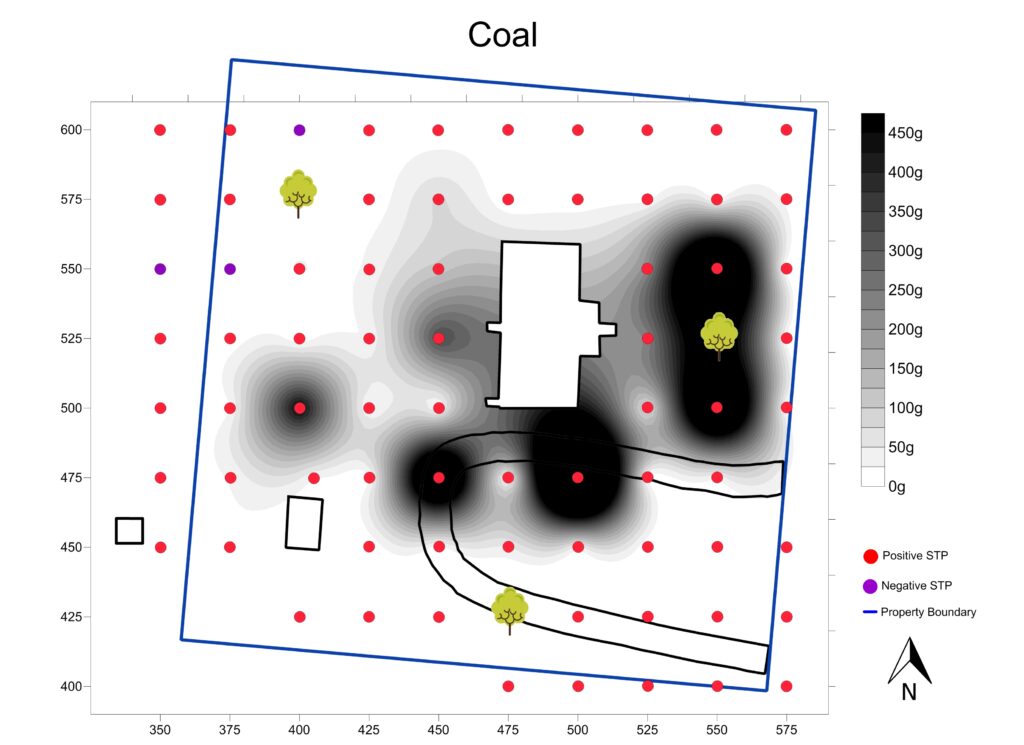

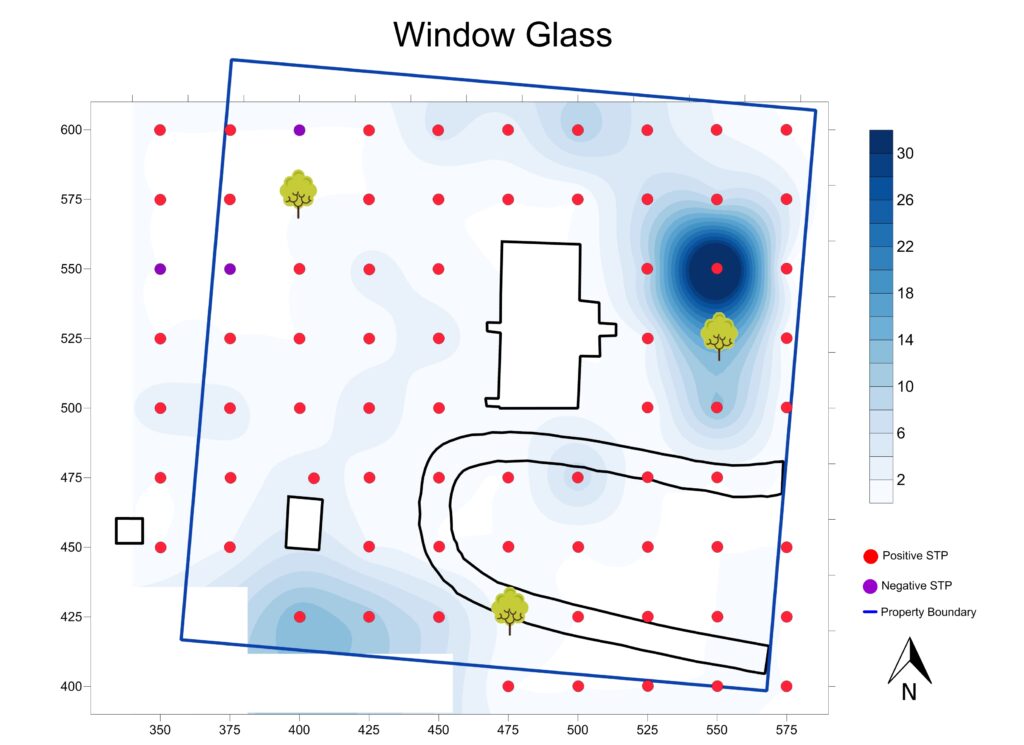

My test unit excavations focused on the front yard based on large quantities of window glass and coal recovered in the area during the shovel test survey. These concentrations were on both sides of the large tree, but so far units have only been dug on the north side where the highest density of window glass was seen.

As described in the previous blog post, the coal density is in part due to three strange “coal holes,” each about three feet in diameter and one foot deep, filled with a compact layer of friable coal and architectural debris. These holes appear to date to about 1923, when the destruction of the old school and construction of the new school took place. Their purpose or even how many of them there might be in the front yard is still a mystery.

The coal concentration is not just due to these coal holes, however. There is a layer containing unburned chunks of coal, ranging from tiny to fist-sized, across the front yard. It starts right below the sod and continues until just an inch or two above subsoil. Mixed in with the coal are numerous school-related and early 20th-century artifacts, strongly suggesting that the coal is a school-era deposit that relates to the 1886-1923 school.

But why was there so much unused coal being dumped? And where is this area in relation to the 1886 school? No direct evidence of the 1886 school has been identified, nor distinct concentrations of architectural material (with the exception of window glass discussed below) that might relate to the earlier school, so it is unclear exactly how this coal and other trash relates to the location of the school. The initial theory was that the coal concentration was in the back yard of the 1886 school but additional units between the coal concentration and the road have not produced any evidence of the school building.

Excavations from the other two schools, Bethel and Glenns/Dragon, can provide an idea of what we should expect to find archaeologically at the site of a demolished school building. Bethel had hundreds of nails per unit, intact pier footings and robber’s trenches, drip lines, hundreds of pieces of window glass, and large brick fragments. At Glenns/Dragon, built only three years before the first Woodville School, the foundations have not been found, possibly due to plowing, but around the location of the school there are again hundreds of nails, numerous brick bats, and other architectural materials like door hinges.

At Woodville, the presence of iron nails decreases moving from the current school towards the road, with the most by far being found near the standing school. Brick was found only in low concentrations in the front yard (aside from two brick bats in one of the front yard units and two large brick fragments in one of the coal holes), only 3,678 grams in total. None of these bricks were in situ and there do not appear to be any robber’s trenches for building piers. There are three confirmed post holes and one other possible post hole, but they don’t not appear to be aligned and they are all either small or shallow. Additionally, all photographs of Gloucester schools from this time show them to be on brick piers, not post-in-ground structures. While it is still possible the school building is located closer to the road and the coal concentration is in its backyard, there is no clear evidence for that, aside from the expectation that a front yard would have been kept cleaner. The 1886 school building’s location can’t be identified based on the current archaeology and until it is identified, the relationship of the coal and window glass concentration to the school building cannot be fully answered.

In addition to the coal, window glass is found in large quantities in this part of the front yard, with over 1,000 pieces in some units. It is most numerous in the transition from Layer B to Layer C, in some instances nearly an inch-thick layer of window glass. Pre-1923 artifacts have been found throughout Layer B with very few post-1923 objects, so the window glass seems to pre-date the destruction of the 1886 building. The full extent of this window glass layer is unknown. The STP map suggests it covers most of the front yard, with the highest concentration being towards the north. Because there were 25 feet between each of the shovel tests and a tree prevented one of the STPs in the grid from being dug, more unit excavation is necessary to figure out the exact extent of the window glass.

The datable artifacts found in the front yard mostly seem to come from the pre-1923 period. This includes a Greentown Glass jelly juice jar tumbler dating between 1894 and 1903, another jelly jar with a patent date of 1906 on the bottom, a celluloid calendar card with a date of 1917 on it, a 1917 penny (although that could have been lost later), a raincoat button that most likely was manufactured before 1924, and non-machine-made bottles. The other artifacts including slate pencils and copper-alloy jewelry also suggest a 19th– or early 20th-century date.

This site is an amazing archaeological resource, and the information that archaeology can provide is especially important since there is so little known about the 1886 school. As is typical in archaeology, the excavations have answered some research questions but have also created many more. For example, we’ve discovered a large trash pile from the earlier school and a large incinerator pile from the post-1944 domestic occupation, but where is the trash from the 1923-1938 Rosenwald School era?

Academic reviews of schoolhouse archaeology have come to the conclusion that traditional shovel testing does not work well for schools due to their low artifact density; instead, systematic unit excavation and excavation based on historical knowledge of the site need to be employed. The shovel tests at Woodville pinpointed the large trash deposit in the front yard, which was due to the amount of coal and window glass, both unusual components of a midden. They did not give any hint of the rest of the amazing artifacts in the front yard, the beads and bottles near the school foundations, or the deposit of writing slate and ash in the middle of the driveway loop.

Importantly, all documentary and oral history evidence from the Rosenwald period suggests they were using wood for fuel at this time, not coal, so there likely won’t be an equally large coal deposit to signal the Rosenwald-era school debris. The Rosenwald-era school trash could be located elsewhere on the property still waiting to be found, undetected by the STP survey.

Thank you Coleen for your most precise descriptions of your work. It is quite fascinating. I love archaeology studies.

I enjoy Colleen’s writing and insights on this subject. As I recall, the coal deposits were a low-quality lignite type; still, it is a valuable commodity to leave on the ground and not in protected coal bins. I’m curious about whether Colleen found burned coal (ashes), which would indicate coal usage at the school vs. just being stored randomly in the open?

Hi! I have not found much ash at all at the school. There was one tiny feature filled with ash and broken writing slate in the modern driveway loop, a few hundred feet away from the rest of the coal. Otherwise, very little to no ash, just lots of coal. However, the stuff in the coal hole does look like it was burned due to how tiny and friable it is.

Coal was sold that included “clinkers” that were unburnable pieces.

At some point this may have been a community coal yard.