In case you missed it: Dr. Walter Reed and Yellow Fever Part 1

When the Civil War broke out, Walter Reed’s older brothers, Tom and James, fought on the side of the Confederacy. The Reed family had left Gloucester County and were living in the Piedmont countryside. Walter, who was barely a teenager at the time, did not experience the full brunt of the war. He and other neighborhood boys hid their families’ horses. They were caught by Federal troops, who soon released the boys but kept the horses. After the war, Lemuel Reed obtained a posting in Charlottesville, Virginia, so that his sons could attend the university there. In 1867, Walter Reed began his studies and was an exceptional student. He took academic courses the first year, and in 1868 studied medicine. Reed graduated third in his class and then traveled to New York where he continued his medical studies at Bellevue Hospital Medical College.

By 1878, Walter Reed was a commissioned officer in the Army medical corps. He was married with one son and stationed in Tucson, Arizona, where temperatures at Fort Lowell were reported to have reached 115 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade. In that hot summer, yellow fever slipped off of a ship in New Orleans to spark the deadliest epidemic of yellow fever ever in the United States. It crept up the Mississippi River Valley to strike terror in Vicksburg, Mississippi; Memphis, Tennessee; Cairo, Illinois; and many smaller towns along the way, as commercial ships and steamers stopped to ply their trade. By the time the epidemic was contained five months later, 120,000 people had fallen ill and 20,000 had perished. The economic toll was put at $100 million dollars. Afterwards, Memphis engaged in a campaign for public sanitation. Although the cause and cure for yellow fever were still unknown, such clean-up campaigns were useful. Germ theories advanced by Louis Pasteur and others were gaining acceptance.

The 1898 Spanish-American War resulted in increased interest in combating yellow fever. Cuba, which was an important U.S. trading partner where Americans owned sugar and tobacco plantations, had been under Spanish control but was struggling to achieve independence. The U.S. took advantage of events that led to involvement in the war and removal of the Spanish from Cuba and some of its other colonies including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The Spanish, who were not in a position to fight a war, soon capitulated. The end of the war was welcome because U.S. troops were falling victim to malaria, dysentery, and other tropical diseases, like yellow fever. After the war, U.S. troops remained in newly independent Cuba and stepped up research to control the scourge.

From the middle of the 19th century, physicians including Carlos Juan Finlay of Cuba asserted that mosquitoes might be responsible for the transfer of yellow fever. Many others believed yellow fever was contracted by exposure to filth, especially in the bed linens and clothes of those who had previously contracted the disease. Finlay published his mosquito theory in 1886, but it was largely ignored. To prove his theory, he experimented with doctors and volunteers who agreed to be exposed to mosquitos and become infected, and some died. These early experiments were conducted in vain, though, because of lax scientific methods. Strict procedures were not followed to ensure the exposed volunteers weren’t contracting yellow fever from other sources they encountered while going about everyday activities.

The Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and 19th-century advances in technologies for transportation and communication made the United States and the world a smaller place, and the spread of infectious diseases became more common. Yellow fever epidemics from Philadelphia to Norfolk to New Orleans raised concerns about public health. While some still believed epidemics occurred because of the vices and sins of people, others saw the value of using medical statistics to direct public health measures. Leaders called for quarantine and sanitation, even though such restrictive and economically stifling measures were unpopular with some. A Yellow Fever Commission, formed after the 1878 Mississippi Valley disaster, concluded that since there were no effective drugs or therapies, and disinfection was generally useless, quarantine was the most effective measure to prevent the spread of yellow fever. Then, in 1879, Congress passed a bill creating the National Board of Health.

Late 19th-century epidemics and medical advances led to the establishment of the Army Medical School in Washington, D.C. In 1893, Dr. Walter Reed, who had spent nearly 20 years at isolated army posts and in the American West, received orders to report to Washington D.C., for duty as curator of the Army Medical Museum with additional duties in the Medical School. He was chosen for the post because of his strong interest in the rapidly evolving scientific field of bacteriology. He received further training in the field at Johns Hopkins University. In 1896, Reed was sent to Key West to investigate a smallpox epidemic. There he met Jefferson Randolph Keen, a great-grandson of Thomas Jefferson and fellow graduate of the University of Virginia Medical School. They became lifelong friends.

After the Spanish-American War, Cuba gained independence, but American forces occupied the island, especially to oversee cleaning of the city after decades of neglect. Diseases like typhoid and dysentery were being brought under control by sanitary measures. Even malaria, another mosquito-borne disease was being brought under control in other parts of the world. Keen, an Army Major, recommended troops in Cuba use mosquito netting.

But yellow fever outbreaks in Cuba and in the United States were still a problem. An outbreak in Hampton was traced to a ship from Cuba docking in the seaport town. Walter Reed began making inspection trips from Washington, D.C. to Cuba related to post-war medical issues. His work on the Army’s Typhoid Board led to improvements in waste disposal. He also investigated a disinfectant for its effect on the spread of yellow fever. He made many friends and was well-respected for his medical research projects. A board was established to investigate infectious diseases in Cuba, especially yellow fever, and Major Walter Reed was tapped to lead the board.

While Reed was admired for his knowledge and research, he had never seen a case of acute yellow fever. In 1900, when he traveled back to Cuba for his first meeting with the Yellow Fever Board, he rushed to the hospital to see his friend Jefferson Keen, who had contracted yellow fever. Fortunately, Keen survived. Reed called a meeting of the four-member board made up of himself, James Carroll, Aristides Agramonte, and Jesse Lazear. Agramonte recorded that they began their work “like men of honor, inspired solely with a noble purpose, by binding ourselves to give out no result as the work of any one man so that whatever came from our labors might be credited to the board as a whole.”

From the Collection of the University of Michigan Health System, Gift of Pfizer Inc.

The Yellow Fever Board couldn’t reproduce yellow fever in any experiments with animals, so they decided to experiment with human subjects. To prove that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, volunteers exposed themselves to mosquitoes that doctors believed to be infected. While these experiments were being conducted, Walter Reed returned to Washington to finish a typhoid research paper. While he was away, two members of the Yellow Fever Board in Cuba became ill with yellow fever and one died. September 1900 was the worst month for yellow fever in Havana in two years: twenty percent of infected people died. When Walter Reed returned to Cuba, Lazear was dead, Carroll was still quite ill, and Agramonte was on leave. It fell to Reed to continue their work, and he knew that it was urgent to conduct experiments in a way that yielded solid scientific proof of the mosquito vector.

On December 9, 1900, Reed wrote a letter to his wife saying, “It is with great pleasure that I hasten to tell you that we have succeeded in producing a case of unmistakable yellow fever by the bite of a mosquito . . . It was Finlay’s theory and he deserves great credit for having suggested it . . .” Walter Reed had also performed rigorous experiments on other theories, and he wrote, “I thank God that I did not accept anybody’s opinion on the subject, but determined to put it to a thorough test with human beings in order to see what would happen.” A dinner to honor Carlos Finlay was attended by dozens of physicians at Delmonico’s in Havana on December 22, 1900.

Once scientists and physicians understood that yellow fever was carried by mosquitoes, they could combat it by eliminating standing water, the breeding ground for mosquitoes. Researchers still didn’t know what virus was carried by mosquitoes and they needed to know this before they could develop a vaccine. It was a long time coming. The virus was not isolated until 1927 and an effective vaccine was not available until around 1950. It would take until the 1970s for sanitation methods to remove about 70% of Aedes aegypti mosquito from parts of the world where yellow fever was common. There is still no known cure for yellow fever.

Walter Reed returned to Washington to a full and busy life with his wife and children. But on November 23, 1902, he died from inflammation following surgery for appendicitis. Some speculated that it was caused by an amoebic infection picked up while he was in Cuba.

Dr. Walter Reed was buried on a small, south-facing hill in Arlington National Cemetery. His good friend Jefferson Randolph Keen selected the site and grave marker inscription: “He gave to man control of that dreadful scourge yellow fever.” Following his death, the Walter Reed Memorial Association was founded to provide for his wife and daughter, and to erect a memorial to him in Washington, D.C.

In the years following Reed’s death, debate arose along political and nationalistic lines over the significance of the principal individuals involved in the discoveries regarding yellow fever in Cuba. Americans credit Reed, who scientifically proved the mosquito theory, while Cubans gave Dr. Carlos Finlay credit for the discovery that mosquitoes transmit yellow fever. Nevertheless, the discovery and proof had far reaching consequences. Mosquito control techniques were so successful in Havana that they were used in Panama and made possible the construction of the Panama Canal. They also allowed for better control of the virus wherever it appeared.

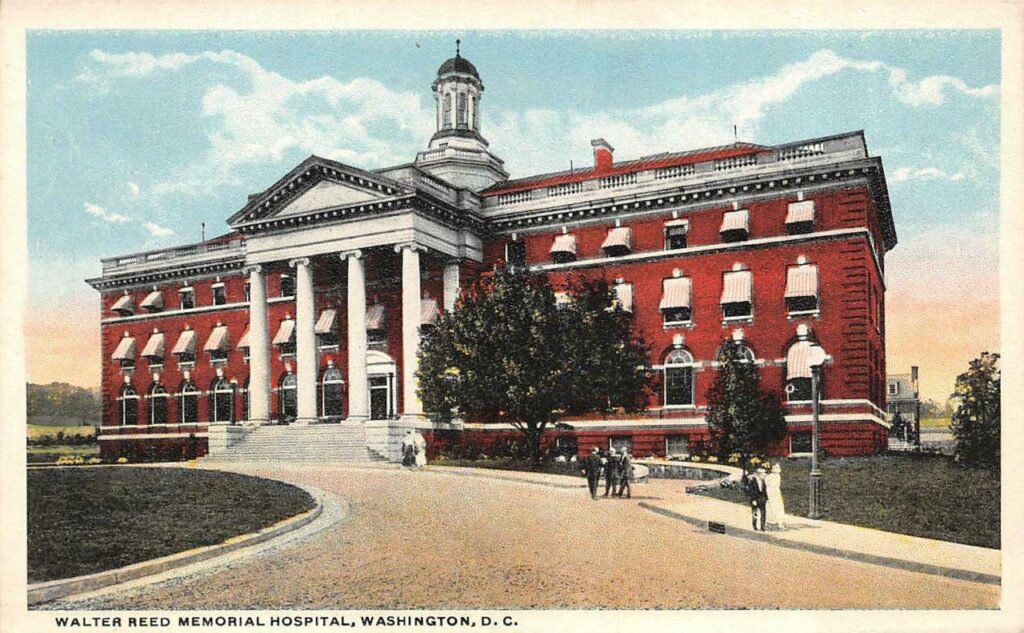

Major William Cline Borden, Reed’s colleague and surgeon, spent the six years after Reed’s death working on building a new army general hospital in the District of Columbia and naming it for Dr. Reed. It was Borden’s dream to combine the Army Medical School, the Army Medical Museum, and the Surgeon General’s Library, all within a new facility on a single campus. Finally, funds were appropriated by Congress and the order dated October 18, 1905 named the hospital the Walter Reed United States Army General Hospital. Growth of the hospital in size and stature was rapid and dramatic, especially after World War II. In 1964, after the death of the last member of his immediate family, the Walter Reed Memorial Association funded a memorial to Walter Reed, which was unveiled in 1966.

In 1927, the Medical Society of Virginia restored Dr. Walter Reed’s Birthplace in Gloucester, Virginia, and opened it as an historic site. One of the earliest historic preservation initiatives undertaken in the county, the Birthplace was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

In 2018, an editorial published in the Journal of Travel Medicine expressed scientists’ concern about the potential threat of a yellow fever pandemic. Because yellow fever could be prevented through mosquito control and vaccination, public health officials in the mid-20th century declared the war on this disease to be won. But increasing population, urbanization, and plane travel have allowed pathogens to spread faster than ever. Yellow fever is one of several diseases that is rapidly spreading between areas where it is known to areas not previously infected, where vaccination enforcement is variable or lax. In 2018, the number of unvaccinated travelers was at its highest in decades. The editorial writer believed it is “only a matter of time” until there is a pandemic of yellow fever in the Asia-Pacific region and response will be hampered by the low number of doses of yellow fever vaccine available.

It is a long and fascinating story from the modest house in which Dr. Walter Reed was born, to the far-reaching impacts of a 21st-century pandemic. From his modest origins, Dr. Reed rose to prominence and made key contributions to the study of yellow fever that have saved millions of lives. The place of his birth, which is 200 years old in 2021, has been preserved for nearly 100 years as a memorial to his life, and serves as an important reminder of 19th-century rural American life.

This 2-part blog was written by Sara Lewis, Fairfield’s Development Assistant.

The author contacted Dan Cavanaugh, the Alvin V. and Nancy Baird Curator of Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia, for assistance with interpretation after reading an article he authored, Walter Reed and the Scourge of Yellow Fever, in UVA Today (https://news.virginia.edu/content/walter-reed-and-scourge-yellow-fever). He suggested a book by John A. Pierce and Jim Writer, Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered Its Deadly Secrets.

THANK YOU FAIRFIELD AND THANE… FOR ATTENDING OUR SPECIAL EVENT…

Nice job, Sara.